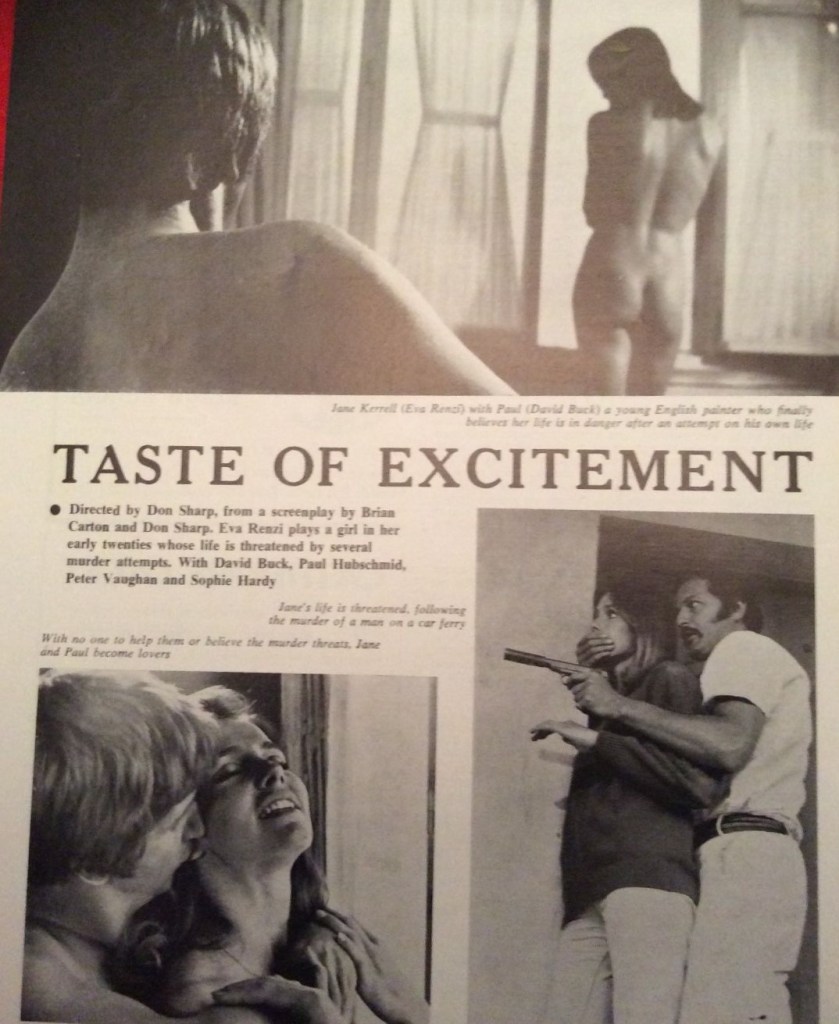

Must-see for all the wrong reasons. An epic of confusion, appalling acting and dodgy accents make this thriller a prime contender for the “So-Bad-It’s-Good” Hall of Fame. Director Don Sharp (The Devil-Ship Pirates, 1964) jibed at star Eva Renzi (Funeral in Berlin, 1966) when he should have concentrated on a script that is over-plotted to within an inch of its life. A couple of kidnaps, casino visit, a sniper, and a vertiginous cliff-top maneuver are thrown in before a truth serum lights up the climax in spectacularly hilarious fashion.

Promising material goes badly awry. English tourist Jane Kerrell (Eva Renzi), floating around the South of France, is being targeted for unknown reasons. A white Mercedes has tried to drive her off the road, mysterious phone calls and visions make her believe she is going mad, that prognosis helped along by handy psychiatrist Dr Forla (George Pravda). And before you can say Surete, Scotland Yard and NATO she is the chief suspect in the murder of a man called Chalker on the ferry to France. Assistance comes in the form of handsome artist David Headley (David Buck) – preposterously famous “I’m David Headley” “The painter?” – who nearly does what’s she’s been complaining everyone else is trying to do, namely knock her down with his car. He specialises in painting nude women and for no reason at all, given he is identified immediately as a lothario, he resists her attempts to take her to bed.

Turns out Jane is something of a boffin, as any self-respecting computer expert would be known in those days, and a millionaire businessman Beiber (Paul Hubschmid), one of Headley’s rich clients, enlists the painter to offer her a job. Of course, he has something else in mind. His company is being accused to shipping unnamed goods to the unnamed opposition, hence the involvement of NATO chap Breese (Francis Matthews).

But nobody is to be trusted, especially as the French police have dismissed her fears as nonsensical. Scotland Yard’s Inspector Malling (Peter Vaughan) throws flames on the fire by not coming to her rescue but planning to arrest her since she is the last person to see Chalker alive. Then it turns out Chalker must have given her a code or secret message before he died. The police take apart her red Mini Cooper in clinical French Connection style but find nothing. That just shows how dumb they are. It never occurred to them, as it does instantly to Headley, to check the carburretor.

By now you’ll have guessed consistency is not this movie’s strong point. You never even know who the sniper Gaudi (Peter Bowles) is targeting his aim is so appalling. There’s even a sinister secretary Miss Barrow (Kay Walsh) with a pronounced Scottish accent in the Jean Brodie class. Headley comes up with an idea to disguise her – by changing her hairstyle (that’ll fool them!! – and astonishingly, in keeping with the bizarre tone, it does).

For someone who is meant to be paranoid Jane is surprisingly trusting, toddling off with clearly-identified villains when fed a line.

You won’t be surprised when Jane ends up trussed and gagged, in her bikini naturally, in a fabulous house with an electrified fence. I can’t resist telling you about the truth serum. Before the evil psychiatrist has the chance to question her he is bopped on the head, Headley having sneaking in before (the dolts!) Gaudi thought to switch on the electric fence. (The electric fence is nullified by the police who just switch off all the electricity in the area.) But when she escapes, still full of the truth drug, when Gaudi calls out to find out where she is hiding, the serum forces her to give the correct answer. In the midst of the danger, Headley takes the opportunity to get an honest answer to the question of whether she loves him. And that’s not the best bit. The final line, given there hasn’t been a decent line all the way through, is a cracker. “Never believe a woman when she is telling you the truth” certainly gives you something to ponder.

So much is held back from the audience that there is never a chance, unlike Charade (1963), of genuine tension. Even the one gripping moment, taking a shortcut along a perilous cliff road, which is well done, is undercut by their pursuer beating them to their destination. The whole thing has an air of being improvised or being devised by someone who thought that twists counted more than characterisation, plot development or relationships.

The acting is so uniformly bad that Eva Renzi actually looks good. David Buck (Deadfall, 1968) is miscast in the slick Cary Grant role. While it is entertaining to see Peter Bowles (The Charge of the Light Brigade, 1968) drop his plummy English accent, his Italian accent fails to pass muster. Peter Vaughan (Alfred the Great, 1969), saddled with the bulk of the murky exposition, does his best. In a bit part, veteran Kay Walsh (A Study in Terror, 1965), holds the acting aces but she doesn’t have much competition.

Director Don Sharp also had a hand in the screenplay so it’s difficult to know who must take most blame, him or colleagues Brian Carton and Ben Healey. This was the alpha and omega of this pair’s movie career.

If you want to see how not to handle a potentially classy thriller tune in. Can’t make up my mind whether to give this two stars for being so bad or four stars for being so bad it’s good. You decide.

And you can do so for free on Flick Vault. Be warned that you have to get past some adverts first. And if you’re wondering what happened to the opening credits, there ain’t any.