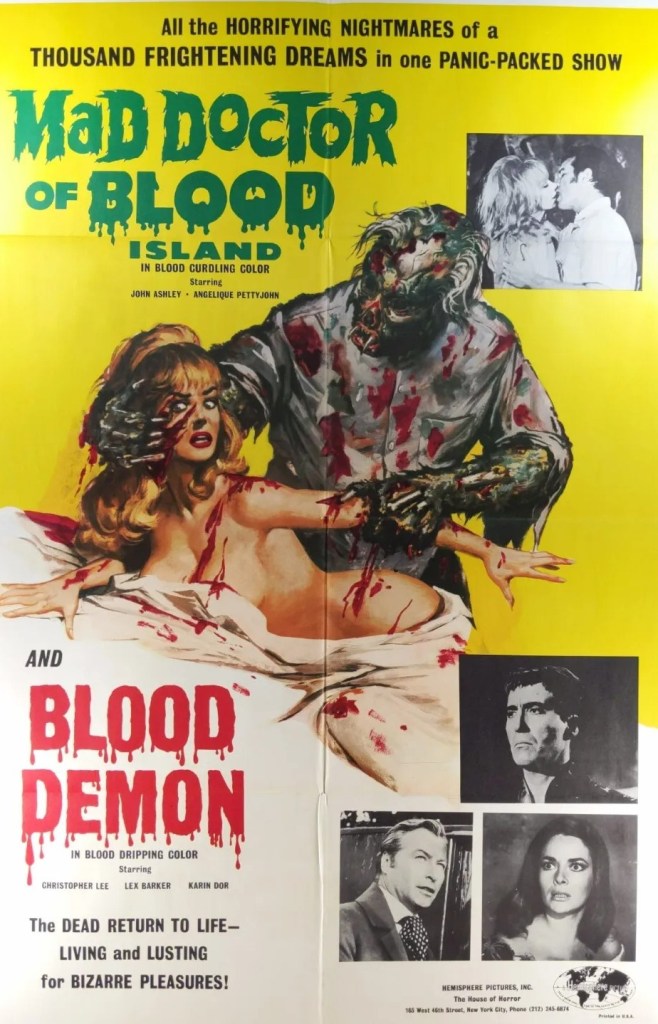

Heavy on atmosphere but not much else, a gender-switch take on the Countess Bathory horror tale (made by Hammer as Countess Dracula, 1971), which sees Count Regula (Christopher Lee) as, oddly enough, being one virgin’s blood short of achieving immortality, thirteen being the vital number, when he is arrested. Condemned to die in traditional fashion, first of all face impaled on a golden iron maiden then body torn apart by a quartet of horses, but not before casting a curse on the prosecutor.

Thirty years later or thereabouts Roger von Marienberg (Lex Barker), son of the prosecutor, turns up seeking the family castle only to find no one will show him the way. And that when he does get going it’s through intermittent fog, past burnt-out buildings and a forest strung with corpses and, it has to be said, a countryside that occasionally takes on an artistic hue, such as one sequence where the coach rides through the countryside with the sky above solid red and the land below solid green.

Along the way he encounters Baroness Lilian (Karin Dor) – the daughter of the evil count’s intended victim number thirteen – and her maid Babette (Christiane Rucker) who go through a routine of being captured and rescued, captured and rescued. When finally, halfway through, we reach the castle, we find the count in a glass coffin awaiting rebirth.

And then it’s like a reality tv show as the visitors undergo a series of torturous obstacles, Babatte hung over a bed of knives while time runs out, Lilian encountering rats and spiders and potentially dropping into a nest of (rather disinterested) snakes, Roger taking a leaf out of the Edgar Allan Poe playbook and facing either the pit or the pendulum.

The count – his awakening shown in shadow the best sequence in the movie – looks like a survivor from A Quiet Place, face desperately white, and frantic to fulfill his quest, with Lilian designated the unlucky thirteenth. Of course, although it took an iron mask and four stout horses to bring him to heel three decades before, he’s not so familiar with the rules governing the undead and a crucific is all it takes to unhinge him.

Very much horror by the numbers without much pizzazz. Lex Barker (Old Shatterhand, 1964) looks as if he’s more worried about his quiff being out of place than anything else. Christopher Lee (The Devil Rides Out, 1968) isn’t in it often enough and, minus the fangs, hasn’t the wherewithal to drum up a scare. Karin Dor (Topaz, 1969), beautiful though she is, doesn’t quite make it as a Scream Queen.

Atmosphere is the best element here, from the opening march from dungeon to execution through long echoing corridors to the Hieronymous Bosch-inspired backdrop of the castle, and the bodies that appear to have dived headling into trees rather than merely dangling from them.

Lex Varker is the key that this is German-made, directed without requisite suspense or fright, by Harald Reinl (Winnetou, 1963).

But like the fog everything is too strung-out