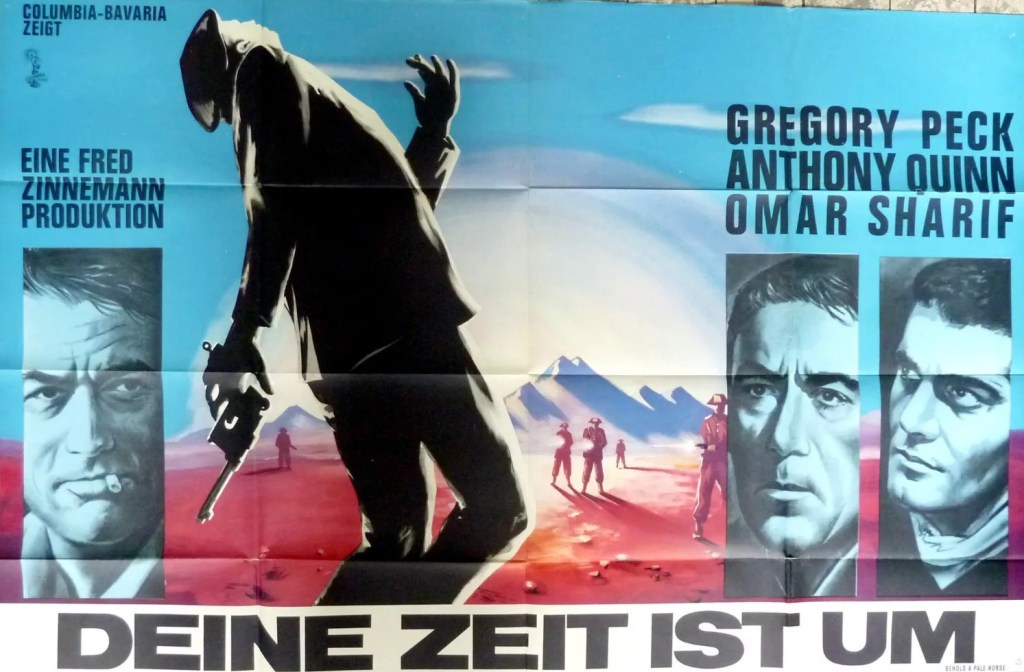

Old causes never die but they do go out of fashion and interest from movie audiences in the issues surrounding the Spanish Civil War had fallen from the peak when they attracted artists of the caliber of Ernest Hemingway and Pablo Picasso. But passions surrounding the conflict remained high even 20 years after its conclusion as indicated in this Fred Zinnemann (The Sundowners, 1960) drama.

Manuel Artiquez (Gregory Peck) plays a disillusioned guerilla living in exile in France, who has ceased raiding the Spanish border town under the thrall of corrupt Captain Vinolas (Anthony Quinn). Artiguez has two compelling reasons to return home – a young boy Paco asks him to revenge the death of his father at the hands of Vinolas and his mother is dying. But Artiquez is disinclined to do either. Heroism has lost its luster. He has grown more fearful and prefers to live out his life drinking wine and casting lustful glances at young women.

In France he enjoys a freedom he would be denied in Spain. He is not hidden. Ask anybody in the street where he lives and they will tell you. This is a crusty old soldier, unshaven, long past finding refuge in memories, but not destroyed either by regret. There is a fair bit of plot, some of it stretching incredulity. The action sequence at the end, conducted in complete silence, is very well done, but mostly this is a character piece.

This is not the upstanding Gregory Peck of his Oscar-winning To Kill a Mockingbird. He is a considerably less attractive character, burnt-out, shabby, grizzled, lazy, easily duped, unwilling to risk his life to see his mother. We have seen aspects of the Anthony Quinn character before but he brings a certain humanity to his villain, bombastic to hide his own failings, coarse but occasionally charming, suitably embarrassed when caught by his wife visiting his mistress and praying earnestly to God to deliver Artiquez into his hands. Omar Sharif has the most conflicted character, forced by conscience to help an enemy of the Church.

However, two elements in the picture don’t make much sense. Paco tears up a letter (critical to the plot) to Artiquez which I just cannot see a young boy doing, not in an era when children respected and feared their elders. And I am also wondering what was it about Spain that stopped directors filming it in color. This is the third Spain-set picture I have reviewed in this blog after The Happy Thieves and The Angel Wore Red. For the first two I can see perhaps budget restrictions being the cause, but given the stars involved – Rex Harrison and Rita Hayworth in the first and Ava Gardner and Dirk Bogarde in the second – hardly facing the production dilemmas of a genuine B-picture.

But Behold a Pale Horse was a big-budget effort from Columbia and while black-and-white camerawork may achieve an artistic darkness of tone it feels artificial. This was never going to be the colorful Spain of fiestas and tourist vistas but it would have perhaps been more inviting to audiences had it taken more advantage of ordinary scenery.

J.P. Miller (Days of Wine and Roses, 1962) adapted the film from the novel Killing a Mouse on Sunday by Emeric Pressburger who in tandem with Michael Powell had made films like Black Narcissus (1947) and The Red Shoes (1948). The film caused calamity for Columbia in Spain, the depiction of Vinolas with a mistress and taking bribes so upset the authorities that all the studio’s movies were banned.