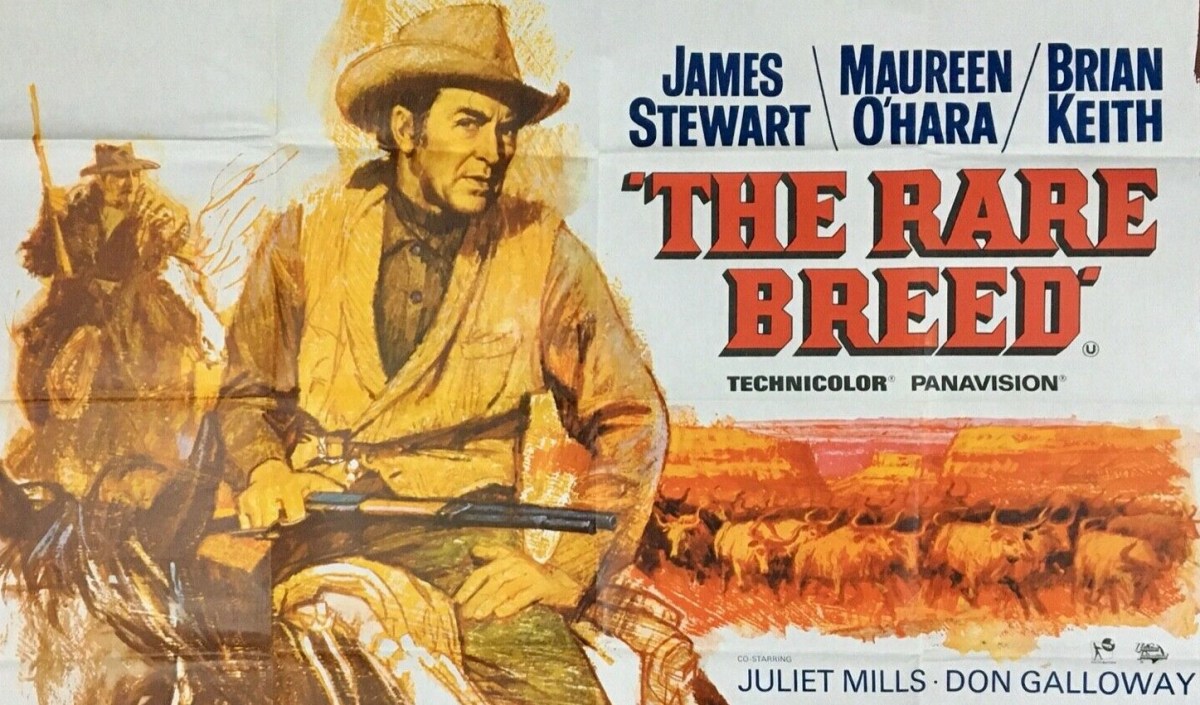

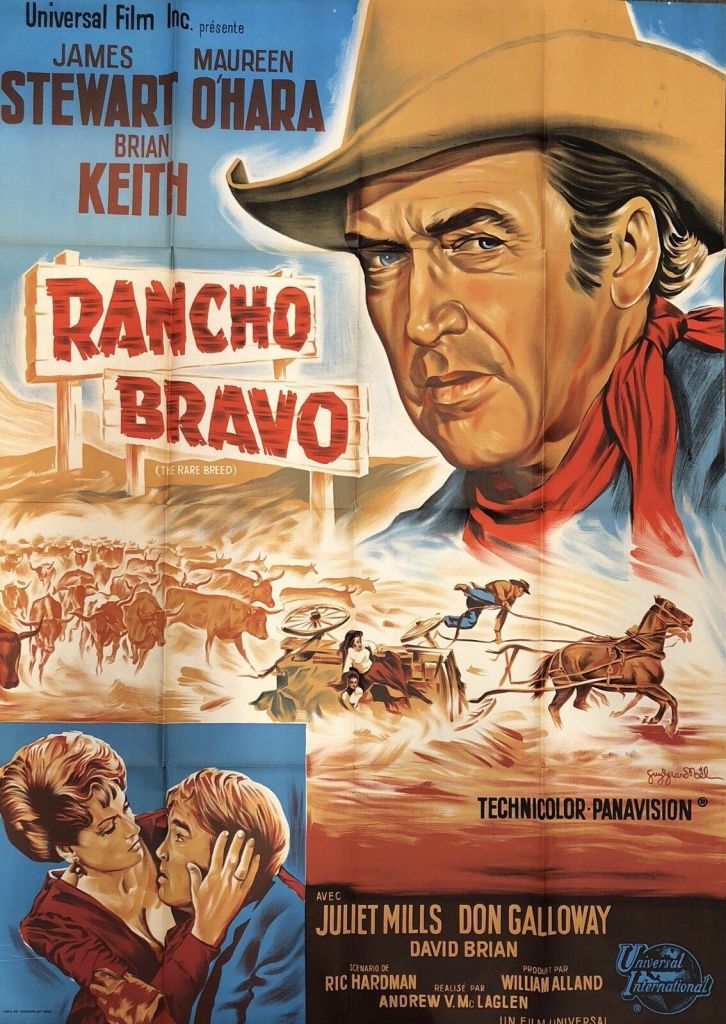

Classic themes of hope, resilience and redemption influence director Andrew V. McLaglen’s follow-up to Shenandoah (1965). Add in a battle against widespread misogyny, thieves falling out, a brilliant stampede and a forlorn hunt that has echoes in the decade-old The Searchers. But other more serious issues are explored. At the film’s core is the question of how a nation built on innovation refuses to countenance change, in other words a country where hierarchy (inevitably male) has begun to impose its preference and how those who suggest alternatives must not just buckle to that collective will but admit they are wrong, a problem that in the half century since the film was made has not gone away.

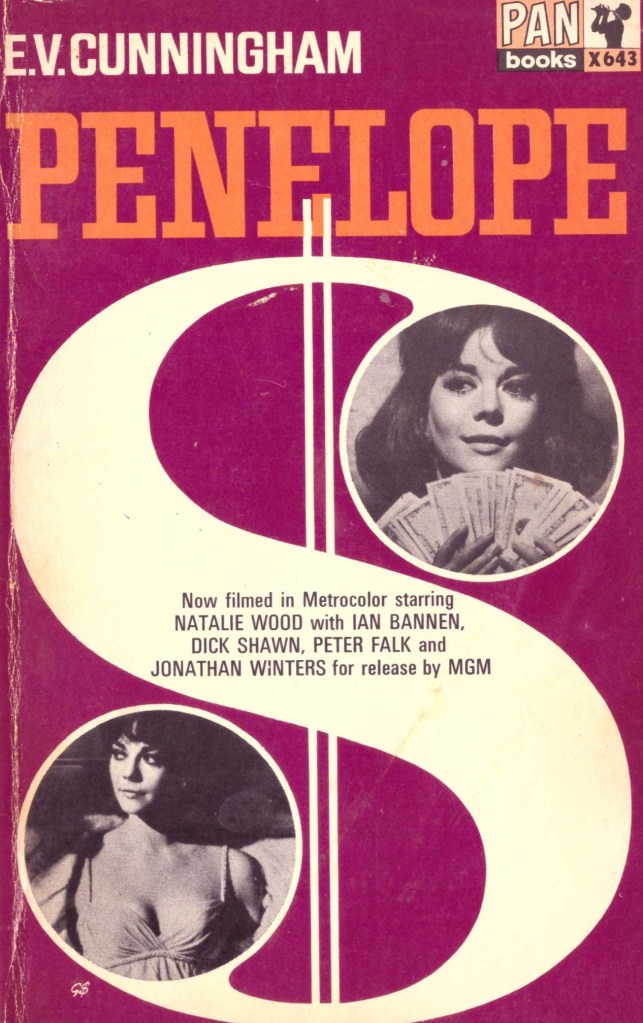

Widow Martha (Maureen O’Hara) and daughter Hilary (Juliet Mills) bring to auction her white-face Hereford bull, a British institution, the first of its kind to be imported (for breeding purposes, you understand) to America where hardy longhorn cattle are the dominant species. Despite being insulted for her temerity in challenging the existing order, Martha is astonished to receive a winning bid of $2,000, only to realize this comes with conditions attached, the buyer assuming his largesse will also win her, a sharp elbow to the ribs dissuading him of this notion.

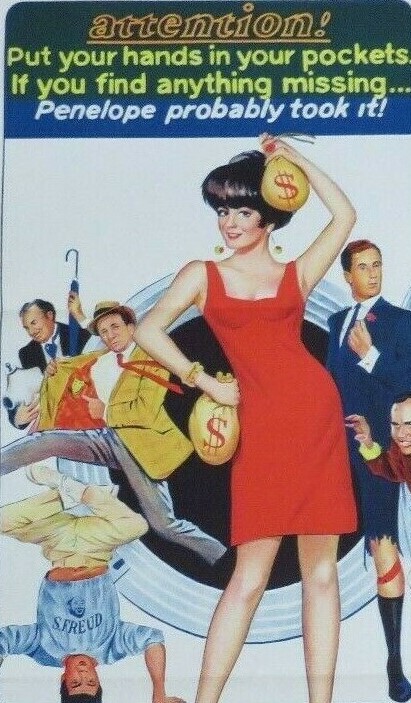

Determined to see the bull delivered to the Texan ranch, Martha decides to accompany the animal on its journey. Wrangler Sam (James Stewart), hired to transport it instead plans to steal it and to keep the dupe sweet until the time is ripe encourages her to develop romantic ideas towards him. When another cowboy, Simons (Jack Elam), with eyes on the same four-legged prize causes confrontation the game is up, though Sam sees the trip through.

Rancher Bowen (Brian Keith) belittles the Hereford bull although viewing Martha as a better proposition, but the only way to discover whether the beast can survive in the territory is to let it loose on the open range where it was likely to encounter blizzards (not so rare in Texas as you might think). Once the bull is set free, the movie shifts onto a question of endurance, not just of the animal, but of the mindset of Martha and Sam. Her faith in her insane idea is tested to the limit and, almost in compensation, a woman needing security/protection et al, she comes to appreciate the attentions of a less wild Bowen.

Both central characters have much to lose and much to face up to. Martha, in accepting she was wrong and letting Bowen into her life, will almost certainly be surrendering her independence (she can still be feisty but that’s not the same thing). It’s a testament to her acting that you can see that faith wilting. Sam, a conniving thief whichever way you cut it (although the storyline gives him something of a free pass), has to face up to the fact that he was planning to con a woman out of the precious possession on which her precarious future was built.

The scenes between Martha and Sam are superb, especially when he is grooming what he thinks will be an easy dupe. Sam, in a purgatory of his own making, almost certainly an outcast were the truth more widely broadcast, attempts to expiate his guilt.

James Stewart and Maureen O’Hara had worked together in Mr Hobbs Takes a Vacation (1962) and there is no denying their screen chemistry. But there’s an innocence that O’Hara rarely displays, the woman in love suppressing those emotions not denying them as perhaps in The Quiet Man (1952). She’s both independent and, if the right man comes along, happy to accept his protection (from the male predators of the West), while at the same time keeping him on the right track and sorting out his world of misshapen priorities. There are some brilliant scenes where something else is going on story-wise and O’Hara is internalizing some deeper emotion entirely. It’s an acting coup for an actress like Maureen O’Hara who would never give up to convey so well a character on the verge of surrender.

This is one of James Stewart’s best roles, far removed from the principled hero of Shenandoah (1965) and returning him closer to the shifty character of Vertigo (1958) adept at self-justification. In the scene where he is found out by O’Hara he is outstanding. It’s not a given that the character will find a way to turn things round and his efforts to redeem himself make the latter part of the picture emotionally involving, especially as this is countered by O’Hara’s own internal battle.

It’s worth pointing out that although the narrative mainly concerns the two main characters, the background is filled with ruthlessness. Not only does Sam feel no compunction about stealing a bull worth $2,000, we first encounter Bowen’s son Jamie (Don Galloway) when he is making off with a herd of his father’s longhorns. The cattle barons use their wealth to “buy” a classy woman and cheat cowboys. And there is further murder along the way.

I was going to mark this picture down for the comedy which seems to amount to endless brawls but I wondered if modern audiences, reared on the never-ending fistfights and wanton destruction that usually indicated the finale of a superhero picture, would accept it quite happily, perhaps even welcome it. While Brian Keith (The Deadly Companions, 1961) stands accused not only of one of the worst Scottish accents committed to the screen – and these days of cultural appropriation – that does not take away from a character who, behind the beard, transitions from loathsome father to something more approaching humanity, in other words wild man who realizes the benefits of civilization.

In fact, the broad comedy serves to obscure a film full of brilliant, cutting, funny lines, generally delivered in scathing tones by the woman. O’Hara to Stewart: “You may bulldog a steer but you can’t bulldog me.” Stewart to O’Hara: “Can I help you with that” and her response “No, they’re clean and I’d like to keep them that way.” And that’s not forgetting the sight of the cowboys whistling British national anthem “God Save the Queen” in order to bring the bull to heel.

I forgot to mention the romantic subplot involving Hilary – in case you were wondering what role she had in all this – and Bowen’s estranged son, Jamie. Juliet Mills (Avanti!, 1970), older sister of child star Hayley, is excellent as the sassy daughter of a feisty woman, Don Galloway (Rough Night in Jericho, 1967) less of a stand-out in his debut, in part because he has to subsume his rage against his father.

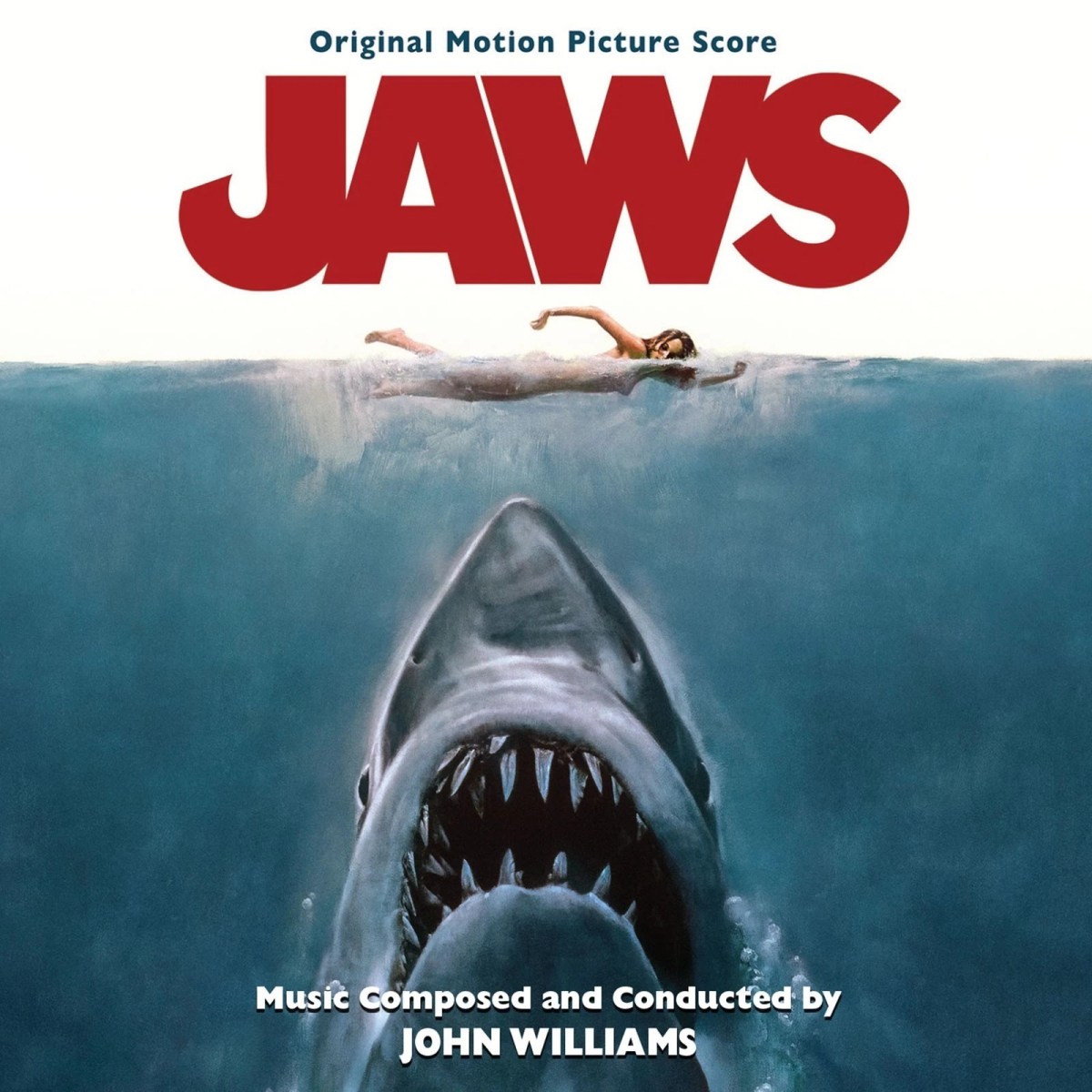

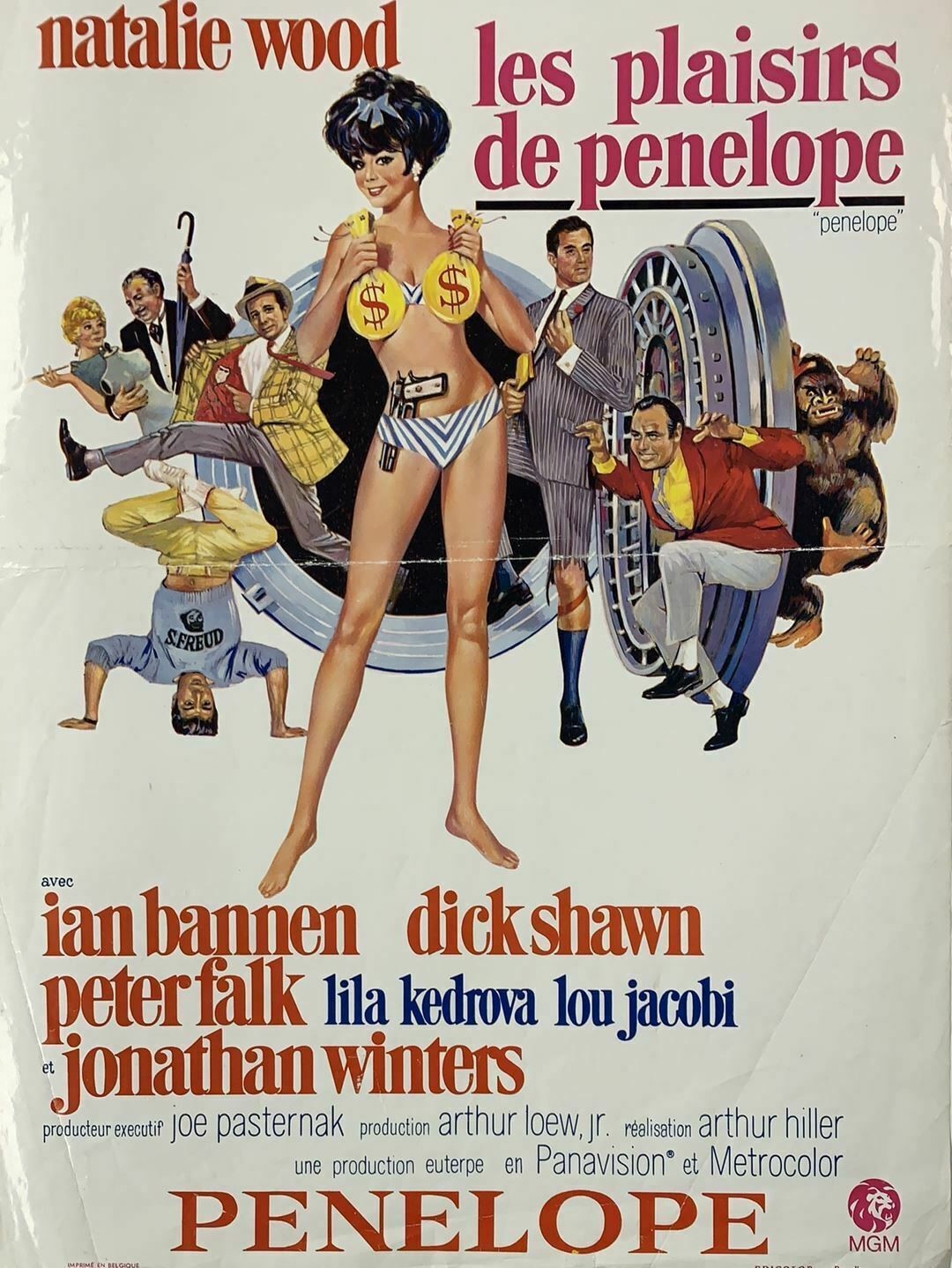

Jack Elam (Once Upon a Time in the West, 1968) is good as always and you will spot in smaller parts Ben Johnson (The Undefeated, 1969), Harry Carey Jr. (The Undefeated), Barbara Werle (Krakatoa, East of Java, 1968) and David Brian (Castle of Evil, 1966). John Williams, masquerading as Johnny Williams, wrote the score.

Setting the comedy aside, this is a more intimate film from director Andrew V. McLaglen compared to the widescreen glory of The Undefeated and the intensity of Shenandoah and for that reason tends to be underrated. There are some wonderful images, not least Sam carrying the injured Jamie in the style of Michelangelo’s La Pieta – an idea stolen by Oliver Stone for Platoon (1986) – but mostly McLaglen concentrates on the actors.