The ensemble picture provided a showcase for new talent. But consider the gender imbalance at work. Only Candice Bergen proved a breakout star of any longevity compared to a flop like The Magnificent Seven (1960) from which six relative newcomers – Steve McQueen, James Coburn, Charles Bronson, Robert Vaughn, Eli Wallach (only his fourth movie) and Horst Buchholz – became top-billed material.

Part of the problem was Hollywood itself, not enough good roles for actresses who weren’t destined for spy movies or to become a decorative supporting player, and who could not headline a western, war picture or (with the exception of Bonnie and Clyde) a hardnosed crime movie. But part of the problem was the structure of The Group. Yes, there’s a 150-minute running time, but there are eight main characters to contend with.

And the story doesn’t have a central focus like The Magnificent Seven where characters are built in asides to the main action but has to meander in eight different directions. Luckily, it still remains a powerful confection, tackling, as if setting out to shock audiences, contentious issues like mental illness, leftwing politics, birth control and lesbianism. What could easily have descended into a chick flick or a glorified soap opera instead pushes in the direction of feminism.

A bunch of wealthy privileged university female graduate friends sets out in the 1930s to change the world only discover, to their amazement, that the male-dominated dominion chews them up and spits them out.

Only Lakey (Candice Bergen), who prefers the company of women, appears to find fulfilment but that’s mostly from running off to the more liberated Paris at the earliest opportunity to study art history though the Second World War puts an end to that.

Kay (Joanna Pettet) seems to have made the best marriage, with a wannabe alcoholic writer (Larry Hagman), but she ends up in a mental asylum. Dottie (Joan Hackett) also views life in the art world, marrying a painter, as the best option only to later prefer a more mundane husband. Priss (Elizabeth Hartmann), the strongest-minded of the octet, lands a man of a stronger, controlling, character.

Polly (Shirley Knight) is the most sexually adventurous. Ostensibly, Helena (Kathleen Widdoes), a renowned traveller, and Libby (Jessica Walter), a successful novelist, appear to achieve the greatest independence and success but come up short in that most important of endeavors, romance. The men, you should be warned, are all one-dimensional scumbags.

The movie focuses mainly on Kay, Polly and Libby. Lakey shows up at the beginning and the end.

At its best, it’s an insight into the world of women, on a grander scale than any of the tear-jerkers of previous decades. But it suffers from too many characters and too little time. It might have been better as a mini-series, though that, obviously, was not an option at the time. The Sidney Buchman (Cleopatra, 1963) screenplay fails to match the intensity of the critically-acclaimed source novel by Mary McCarthy, a huge bestseller.

It’s a surprising choice for Sidney Lumet (The Pawnbroker, 1964), more mainstream than his general output, but while he clearly presents the characters in sympathetic fashion, his hallmark tension is missing.

Mostly, it works as a time-capsule of a time-capsule, a movie about the 1960s optimism of 1930s optimism, and the obstacles faced by both.

Only Candice Bergen (Soldier Blue, 1970) approached the level of success achieved by The Magnificent Seven motley crew, achieving top-billed status in a number of films and her screen persona, possibly as a result of this movie, was often independence. Leading lady in Will Penny (1968) and Support Your Local Sheriff (1969) was the height of success for Joan Hackett.

Already twice Oscar-nominated as a Supporting Actress, Shirley Knight was the best-known of The Group, but was only thereafter top-billed once, in the low-budget Dutchman (1966) although she won critical plaudits for The Rain People (1969).

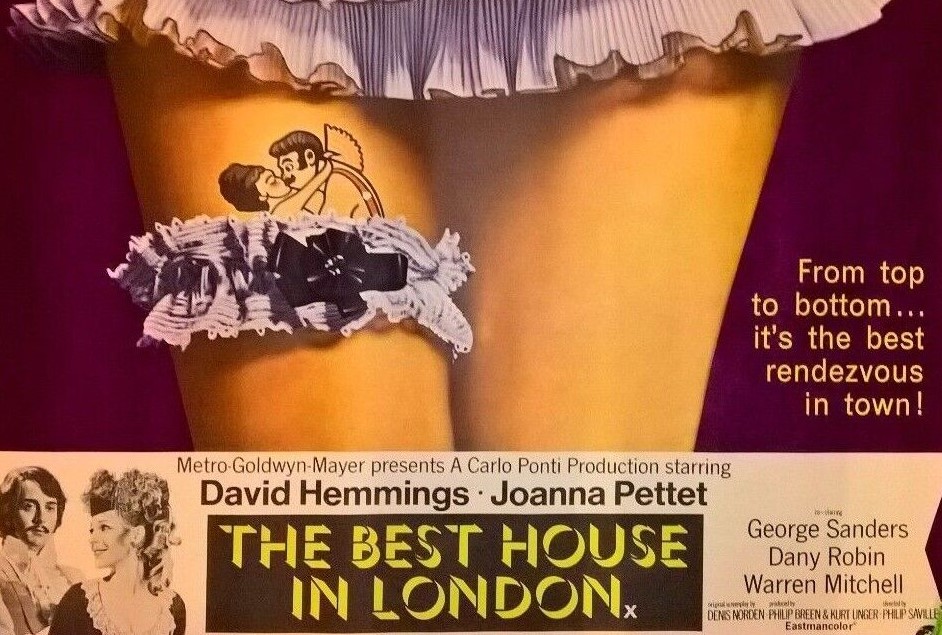

An Oscar nominee for her debut A Patch of Blue (1965), Elizabeth Hartmann was top-billed in You’re A Big Boy Now (1967) and then fell into the supporting player bracket. Never top-billed, Joanna Pettet was a strong co-star for the rest of the decade but that was marked by flops like Blue (1968) and The Best House in London (1968) and she drifted into television.

Best known for Number One (1969) and Play Misty for Me (1971) Jessica Walter failed to achieve top-billing. Though, as a result of this review, it has been pointed out to me (thanks Mr Film-Authority) that I glossed over her brilliant performance in television show Arrested Development (2003-2019); in fact, if your search for her on imdb that TV series is the one that pops up first.

Most of the actresses did have long careers, sustained by leading roles in television or bit parts in movies but when you consider the success visited upon the group known as The Magnificent Seven you can’t help thinking this was a whole generation of talent going to waste because they could not be accommodated by the Hollywood machine and did not fit the industry prototype.

For another example of gender disparity you could compare the consequent comparative success of the stars of Valley of the Dolls and The Dirty Dozen, both out the following year.