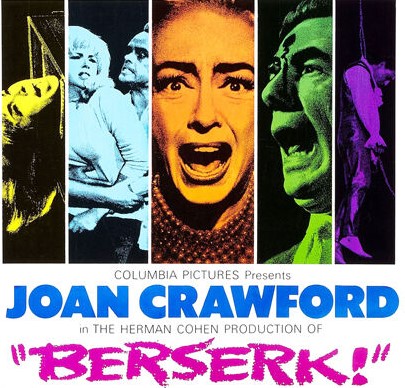

“Murder is good for business,” declares magnificently callous circus boss Monica (Joan Crawford). And so is nostalgia. Interrupting the action every ten minutes or so with the kind of circus act – courtesy of legendary British ringmaster Billy Smart – that you couldn’t see these days is probably going to win more viewers than seeing Joan Crawford in late vintage nastiness. Roll up, roll up for the elephants ridden by glamorous lasses, death-defying (or not so much) high-wire acts, prancing horses, knife-throwing, cutting a woman (and who better than a sequined Diana Dors) in half, and “intelligent” poodles (is there any other kind?).

Step aside John Wayne (Circus World, 1964), whose magnificent showmanship has nothing on circus master Monica, calling the shots and not just in the ring. She rides roughshod over business partner Albert (Michael Gough), pushes back into his box newcomer Frank (Ty Hardin), and packs daughter Angela (Judy Geeson) off to boarding school to shut the book on maternal instinct in case it gets in the way of running the show.

Throw in a good few hapless coppers, including a toff – Monica being such a big noise it requires the involvement of a Commissioner (Geoffrey Keen) and a Superintendent (Robert Hardy) – who pop up sporadically and show surprisingly little skill for detection beyond standing over a corpse or murder implement and making a pronouncement. Naturally, such an atmosphere is riven with jealousy and it doesn’t take much to start a cat fight, no surprise to see Matilda (Diana Dors) in the thick of it.

When her star act dies (murdered) on the high wire and Monica looks around for a replacement, she happens upon pushy Frank (Ty Hardin) who not only walks across the tightrope blindfold, but operates without a safety net and should he fall will land on a series of nasty spikes. He wants to share her bed and her business, but has some dodgy backstory, hints of some incident in Canada seven years ago.

So just as Monica reckons the thrill of possibly seeing death occur in front of their eyes will pull in the punters, that could be (though I doubt it) an ironic nod at the cinema audience since, as in all serial killer pictures, viewers are calculating who will be killed next, and not so much who the murderer is, but who will survive at the end. Luckily, this is British and made in times when the censor exerted a tighter rein, so you can be sure nobody’s going to meet a sticky end just because they’ve had illicit sex.

As if her employees were scary beasts, Monica beats them into submission, though, in fact, outside of Frank, nobody’s got the guts to challenge her. And it being the 1960s and forensics not much in evidence and, frankly, the producers not much interested in rounding up any suspects, you just sit back and wait to see who will be next. Will someone scare the prize elephant into misplacing a foot and crushing to death the beauties lying on the ground so that it can daintily step over them? Will the knife-thrower miss his marks or the spinning wheel containing his human target be rigged to go awry?

My money was on the poodles attacking their mistress for making them jump over a skipping rope. I hadn’t quite seen coming Albert being foolish enough to lean against a post with his head positioned exactly beside a hole so that from behind someone could hammer a spike into it. That should have made Monica a suspect because he wanted out of the business, except she has stolen and burned their contract and not a single soul in the entire circus appears to know that he even was her business partner.

Angela, when she turns up accompanied by a headmistress, appears to be a chip off the old block, turfed out of yet another school for “causing trouble.” Monica looks as if she was born to be trouble, and you can imagine the machinations that led her to owning a circus. There’s a surprisingly tender mother-daughter reunion and the daughter is soon enrolled in an act.

The ending seems straight out an Agatha Christie novel, take the least likely contender and make them the villain, with psychobabble as justification.

I have to say that I enjoyed this, as much for the circus acts as for seeing noir queen Joan Crawford (Mildred Pierce, 1945) returning to the tough-as-they-come persona of Johnny Guitar (1954) rather than the theatrics of Whatever Happened to Baby Jane (1962). A pre-lugubrious Michael Gough (Batman, 1989) and a non-blousy Diana Dors (Hammerhead, 1968) add to the treats. Maybe Sidney Sweeney (Immaculate, 2024) consulted the Judy Geeson (Prudence and the Pill, 1968) playbook in assessing the career value of appearing in a horror movie. Ty Hardin (Custer of the West, 1967) is miscast, especially in his high-wire wobbles, though anyone thinking they can act Ms Crawford off the screen should be taken away and locked up.

Jim O’Connolly (Vendetta for the Saint, 1969) directed from a script by the team of Aben Kandel and producer Herman Cohen (Black Zoo, 1963).

Nostalgic fun.