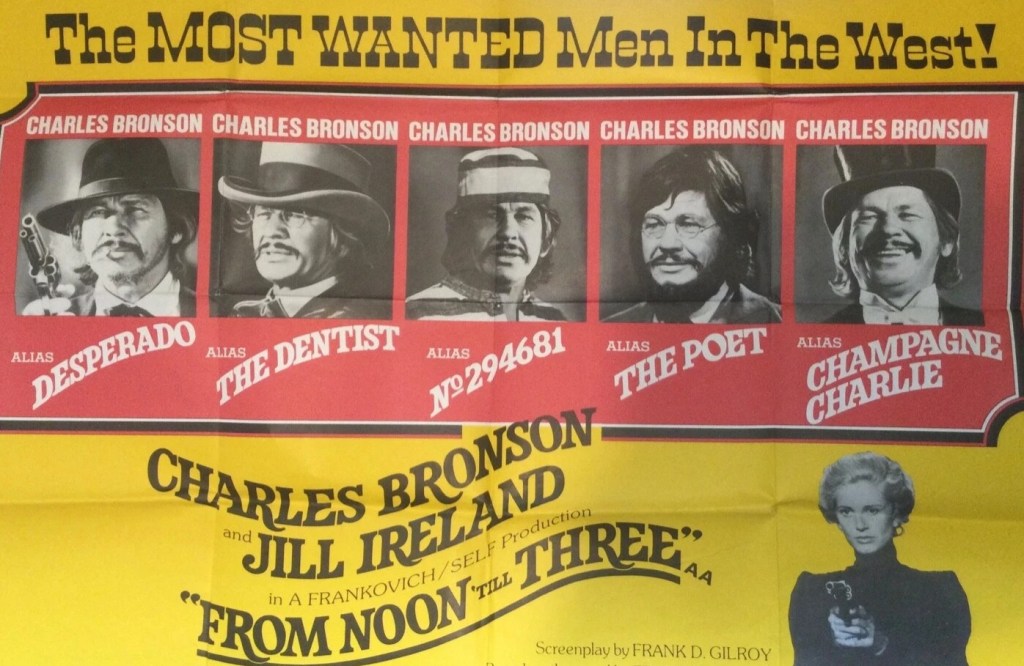

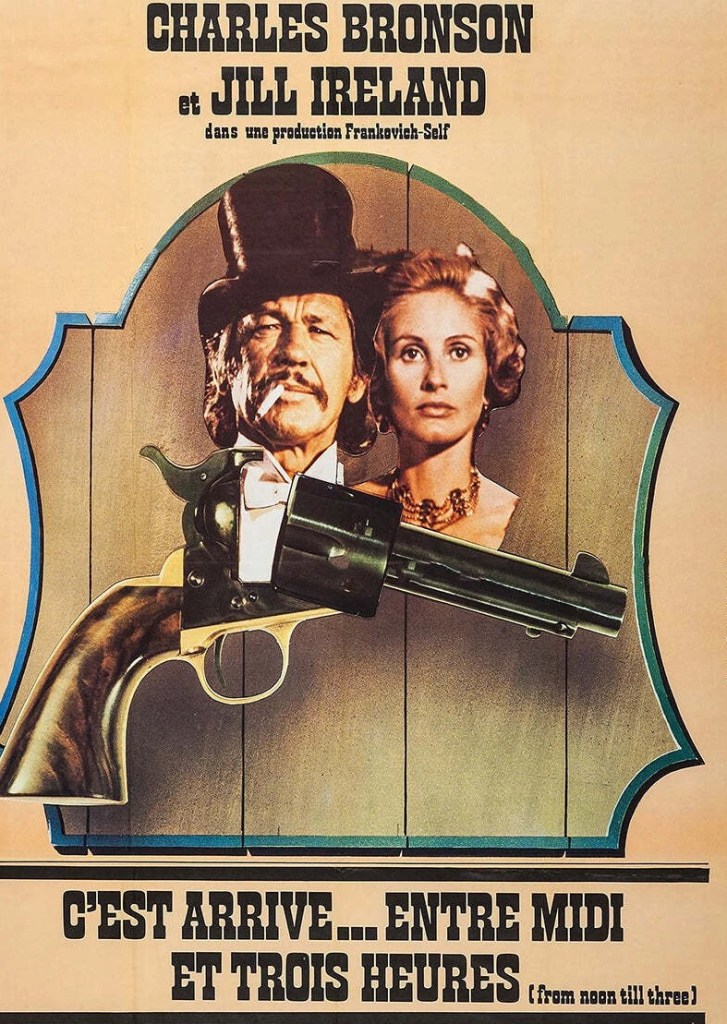

The advertising gurus earned their corn on this one because it must have come as a shock for all concerned, studio and audiences alike, to discover that star Charles Bronson (Farewell Friend, Adieu L’Ami, 1968) was engaged in a rapid reversal of his screen persona, an experiment that ended with the poorly received From Noon Till Three (1976). Sold as an action picture, this struggles to fit into the genre, what with most of the elements of rescue misfiring or D.O.A.

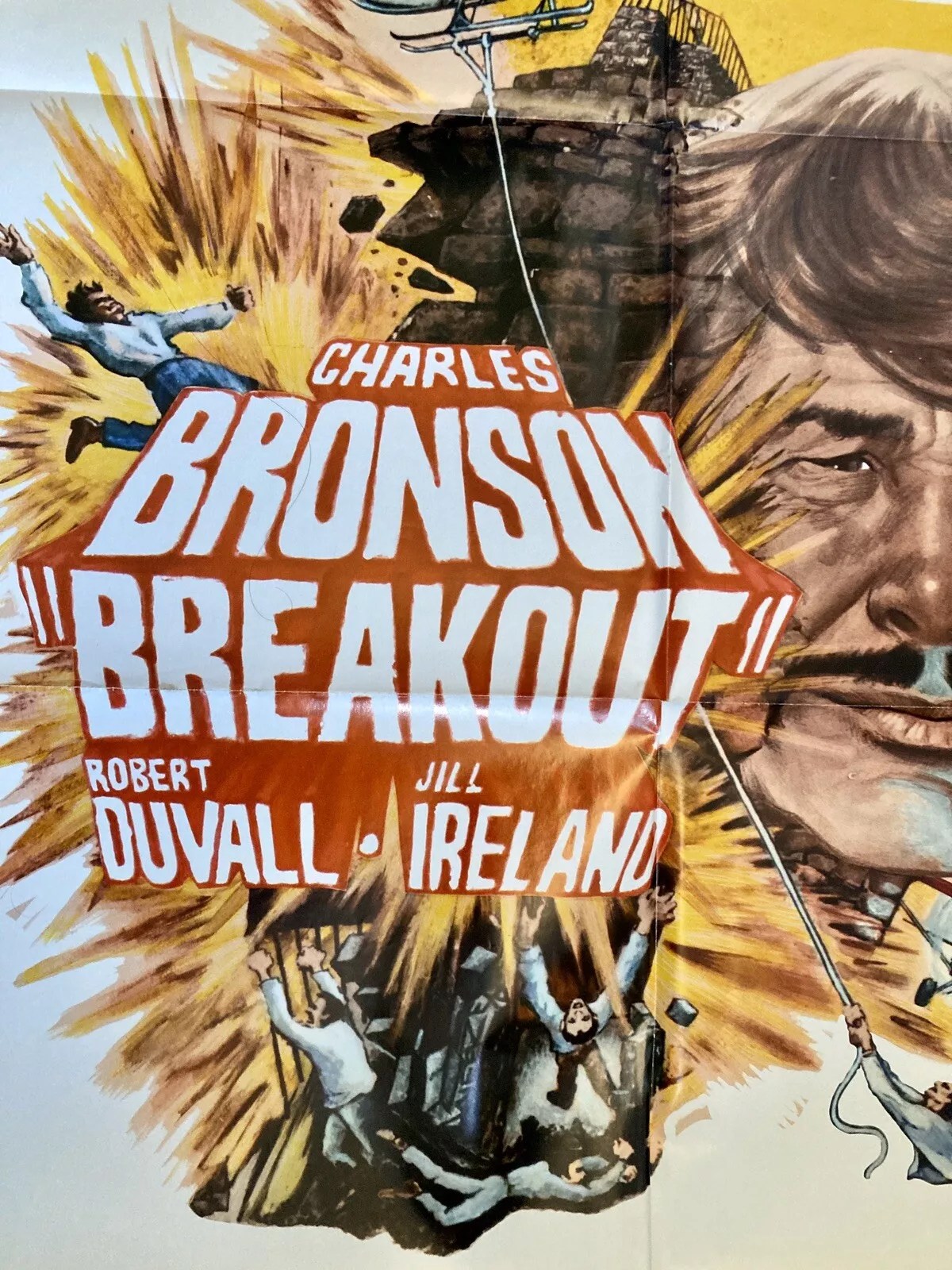

The poster people were so stuck for ways of selling the picture they resorted to using an image of an explosion in a manner that indicated it was key to the actual breakout when in fact it was related to a random incident. The highlight of the picture, the breakout itself, despite the best efforts to generate tension though the application of a 10-second escape window, is as mundane as all get-out, a helicopter basically loitering in a prison courtyard until the prisoner to be rescued saunters out.

Not only does the movie jettison the Bronson tradition of uncompromising tough guy but it sets up constant screen partner Jill Ireland in a more interesting role than normal while skirting a Casablanca-style romance.

The story itself gets off to a mighty confusing start. Nefarious businessman Harris Wagner (John Huston) arranges, for reasons that are unclear, for grandson Jay (Robert Duvall) to be incarcerated in a Mexican prison. Your first double take as an audience is the purported age gap. Huston was, in reality, was just past 70 years of age while Duvall was 44 – and never a chance of that actor playing younger – so you are left wondering how in heck did they contrive to be grandfather and grandson.

Putting that to one side, the first 15-20 minutes of a lean 96 exclude Bronson altogether while director Tom Gries (Will Penny, 1968) builds up the tale of failed rescue attempts by Jay’s wife Ann (Jill Ireland) and the sadistic nature of prison overlord J.V. (Emilio Fernandez) who has a penchant for burying prisoners alive or taking bribes to let them escape before promptly reneging on the deal. Eventually, for reasons unexplained, Ann turns to bush pilot Nick (Charles Bronson) who runs a seat-of-the-pants operation with the kind of plane that looks like it’s held together with string.

He’s not your usual monosyllabic grump, but an overconfident wide boy, the bulk of whose schemes fail to work. A modern audience is going to turn up its nose in any case at one plan that involves faking a rape to create a distraction for the prison guards rather than going down the simpler route of Raquel Welch in 100 Rifles (1969) and Marianna Hill in El Condor (1970) of giving the lascivious guards something to ogle.

And another proposal only works because it’s handed a get-out-of-jail-free card when the guards who make a point of groping every female visitor, in theory to check for contraband or concealed weapons, avoid doing so with Nick’s sidekick Hawkins (Randy Quaid) when he dresses up as a woman.

There’s not enough time for any genuine romance to develop between Nick and Ann, a notion that’s undercut in any case by the fact that she’s trying to rescue her beloved husband, but that does allow for more friction than was normal in their pictures. Takes her a long time, understandably, to trust this untrustworthy fella, what with his schemes that rarely work.

For tension we are almost entirely reliant on the bad guys, J.V. indulging in bits of sadism, someone on the inside always knowing of the plans ahead of time, or of Jay being so debilitated by his stay in prison that he seems too out of it to keep his appointment with freedom. There is a quite barmy assumption that should a stray helicopter land in a prison courtyard that none of the other inmates will think to hitch a lift out.

There is some good value here in the Bronson/Ireland partnership trying to shake off what they saw as the shackles of their joint screen persona, or perhaps wanting to re-validate Ireland’s place in the team after Bronson did exceptionally well in her absence in Death Wish (1974). But the story’s an odd one, a kind of discount-store escape, with Bronson essaying the kind of character usually left to such supporting acts as Warren Oates or George Kennedy.

But there’s just not enough that’s new here – the unfairly underrated From Noon Till Three showed how to ring in the changes – to justify Bronson’s inclusion although the Bronson/Ireland dynamic does undergo interesting change. Robert Duvall (The Rain People, 1969) is also acting against type, devoid of the bluster that was his calling card. Randy Quaid (The Last Detail, 1974) has a quirky part.

Tom Gries did well enough in Bronson’s eyes that he was selected for the follow-up Breakheart Pass. Too many hands on the screenplay tiller – Marc Norman (Shakespeare in Love, 1998), Elliott Baker (A Fine Madness, 1966) and Howard B. Kreitsek (The Illustrated Man, 1969) adapting the book by Warren Hinckle, William Turner and Eliot Asinof – suggested nobody really knew how to make this work. And they were right.

Interesting shift in the Bronson persona but a misnomer on the action front.