If ever there was a case to be made for six-track stereophonic sound or, for that matter, split screen Grand Prix would form the first line of defense. That it was made in Cinerama 70mm was merely a bonus. Most roadshow movies start with an overture, a ten-minute or so musical introduction that would thematically at least give the audience some indication of the picture they were about to watch. Thrumming and roaring engines formed the montage opening to Grand Prix, a noise that almost shook a cinema to its foundations.

Cinerama had been built on its ability to create almost primeval effects. There was always a downward rush, a runaway train, a roller coaster, something to set an audience on the edge of its seat in pure exhilaration. But the visual had nothing on the aural and what set Grand Prix apart was danger, that constant thrum of engines rising to impossible crescendos. Split screen allowed the director to tell several stories at once as competitors chased each other round perilous circuits at a time when death was a racing driver’s constant companion and in fact of the thirty-two professional participants including Graham Hill, Jim Clark, Juan Fangio and Jack Brabham five were dead within two years of the movie’s completion. Nobody needed to remind an audience how hazardous the sport was, they could read about the continuous carnage in the newspapers, but what was less easy to convey, although such events were well attended, was the pure thrill of being at a race meeting. Grand Prix set out to rectify that problem.

At nearly three hours long it had room to tell several stories and in that respect it was more of an ensemble picture than something like Lawrence of Arabia (1962) which took even more time to tell just one story. Many of these stories came to an abrupt end as the character died in an accident.

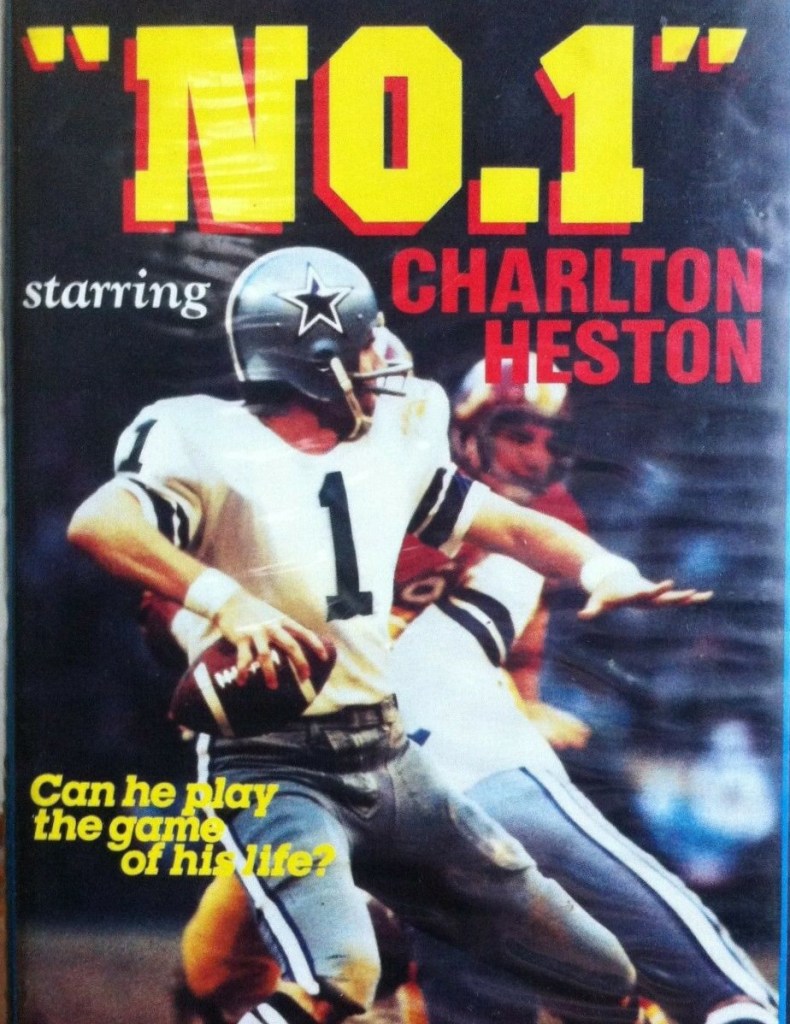

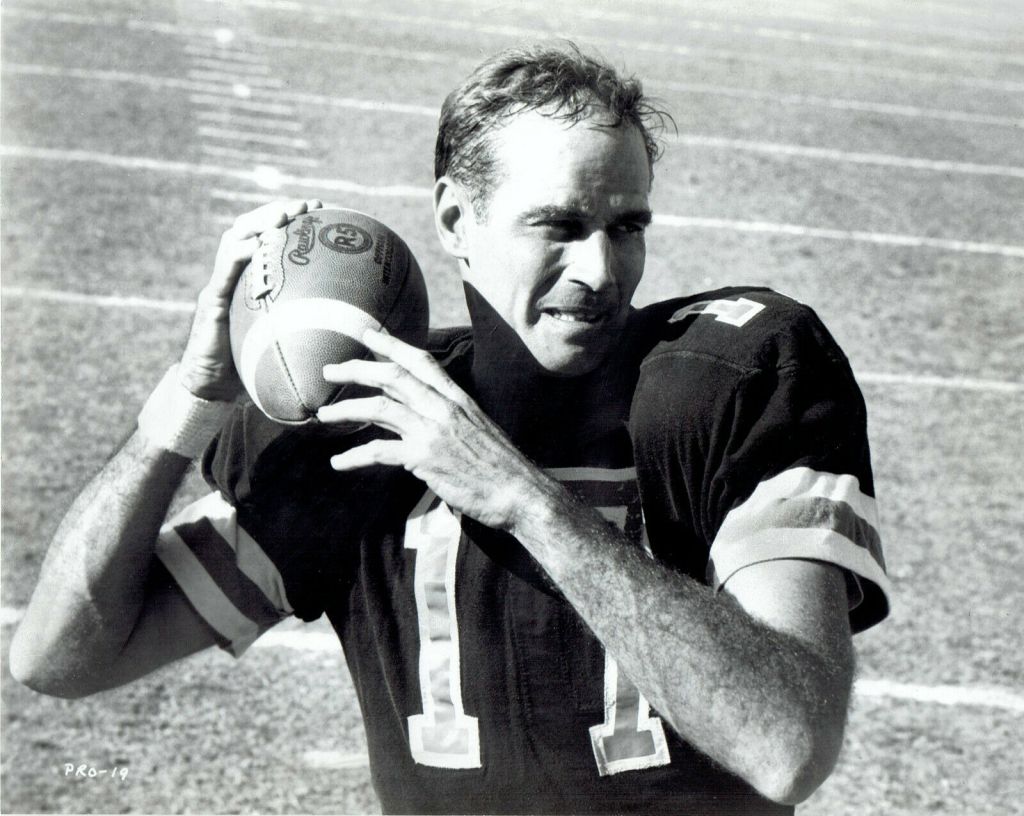

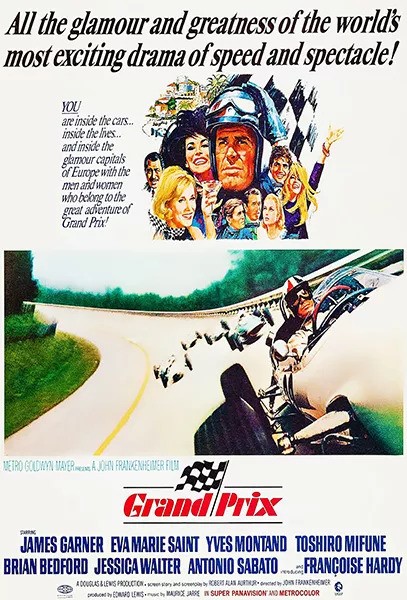

Steve McQueen and Paul Newman, both racing aficionados, were front runners for the leading role but it went instead to James Garner, also a racer who did all his own driving (though not necessarily at the speeds indicated). And to properly represent the competition it required an international flavor so other drivers were played by Yves Montand (The Wages of Fear, 1953) in a part first offered to Jean-Paul Belmondo and Antonio Sabato (in his second film) with Adolfo Celi (Thunderball, 1965) as the Ferrari boss and Toshiro Mifune (Seven Samurai, 1954) as a Japanese team owner. Swedish star Harriet Andersson (Through a Glass Darkly, 1961) was cast as the female lead but dropped in favour of Eva Marie Saint (Exodus, 1960) in a role turned down by Monica Vitti (Modesty Blaise, 1966).

Garner and Saint had previously worked together in thriller 36 Hours (1964) and it said a lot for his marquee credentials that he was still best known for The Great Escape (1963). Although he had reached top billing status, films like The Art of Love (1965) and Mister Buddwing (1966) did not deliver commercially. Saint’s career had been as peripatetic after Exodus (1960) as before, star of All Fall Down (1962) but third-billed in The Sandpiper (1965) and second-billed in The Russians Are Coming, The Russians Are Coming (1966), the latter two both big hits.

Frankenheimer had directed Saint in All Fall Down and enjoyed a distinguished career with The Birdman of Alcatraz (1962), The Manchurian Candidate (1962) and Seven Days in May (1964) although the high regard in which he was generally held was somewhat tarnished by The Train (1965) and thriller Seconds (1966), the latter a spectacular flop. Grand Prix was not only the biggest film of his career, though The Train had given him a grounding in action, but also his first in color. The movie was filmed on existing legendary circuits with Formula 3 racing cars adapted to look like Formula 1 and a thousand other incidental details including an appearance by a Shelby Mustang (with Carroll Shelby as technical adviser) that made it an accurate depiction of the sport. Eighteen cameras were used to film the races.

The narrative arc follows the Grand Prix season and while the actual competition dominates the movie it is against the background of the emotional turmoil the sport wreaks on the drivers and the wives and girlfriends who have to live with the knowledge that their partners might not come home at the end of the day. Garner is considered too reckless for the top spot in a racing team and in a bid for redemption signs for a new company. Former world champion Montand is coming to the end of his career. English actor Brian Bedford makes his mainstream movie debut as a driver recovering after a horrific crash caused by Garner. The emotional subplots comprise Garner having an affair with Bedford’s wife (Jessica Walter); Montand embarking on an affair with Saint who plays a magazine writer, with French actress Francoise Hardy (better known as a chanteuse) involved with Sabato. In addition, there are some telling sequences in which the drivers unload about their fears.

Frankenheimer does a terrific job in marshalling all the effects and the minute details, and the fact that there is no big star in the mix makes the battles between the characters more realistic.