The indie movement wasn’t embraced back in the day the way it is now. Occasionally an indie auteur would find favor – John Cassavetes (Shadows, 1958), for example – although it was another decade before he made another movie that carried his particular stamp. With such an abundance of movies arriving from Sweden, Italy and France, critics didn’t have to go far to find material from outside the limited Hollywood prism that they could pump up and make themselves feel important.

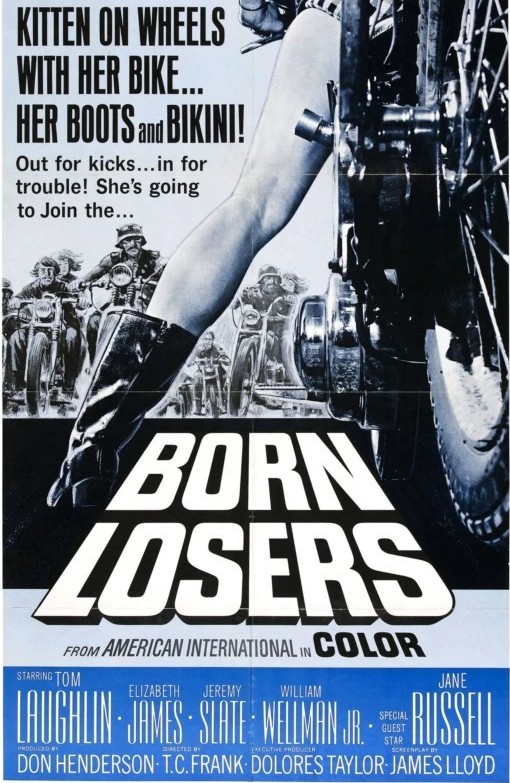

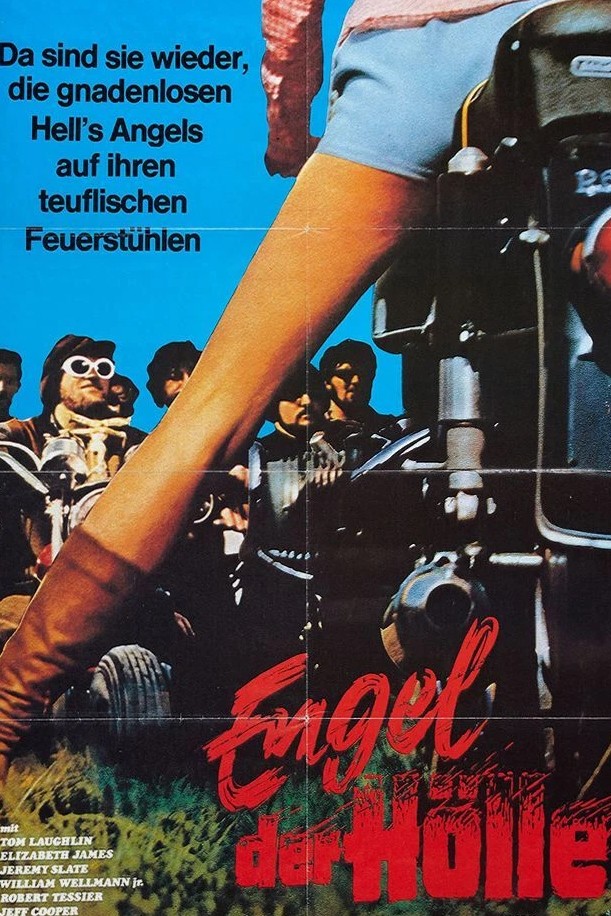

So indie writer-producer-director-actor Tom Laughlin failed to gain notice. There had been no upsurge of critical support for his first two features, The Young Sinner (1961) and The Proper Time (1962), both of whose subject matters should have generated some coverage. In fact, they’re still ignored, not a single reviews for either on Imdb unless you count TV Guide. So when he came to his third picture, The Born Losers, he hid behind anonymity, the movie helmed by “T.C. Frank” and produced by “Don Henderson” with “James Lloyd” (in reality female lead Elizabeth James) allocated the screenwriting credit.

And it was, ostensibly, a biker pic, so no self-respecting critic was going to give it the time of day even though The Wild Angels – 83 critical reviews on Imdb – the previous year had attracted attention though largely through its nepo cast, Peter Fonda and Nancy Sinatra the children of Hollywood legends, in which the bikers were cast as innocent victims of authority.

So critics failed to note that The Born Losers was pretty much the first movie with an ecological theme and that it was probably only the second to deal with racism against Native Americans – Abraham Polonsky, on the other hand, got massive critical mileage for covering the same theme in Tell Them Willie Boy Is Here (1969).

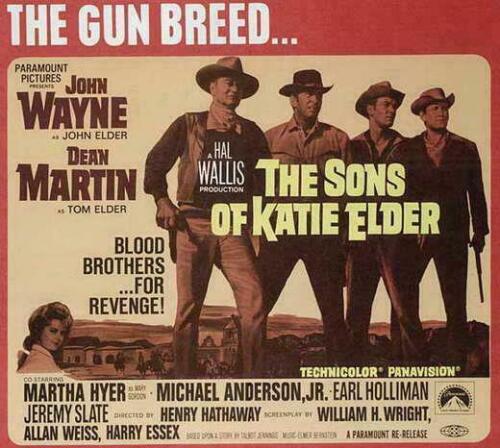

And there’s nothing redemptive about these bikers, not given a free pass as in Wild Angels or deified as in Easy Rider (1969). But the picture certainly emphasizes their attraction, especially to teenage females entranced by what they view as an exciting alternative to Dullsville, USA. Girls are seduced by the image of bikers being akin to old-style cowboys, pioneers of the west enjoying a freedom few others dared even pursue. In the Californian sun girls jiggle around in bikinis, excited at the revving bikes.

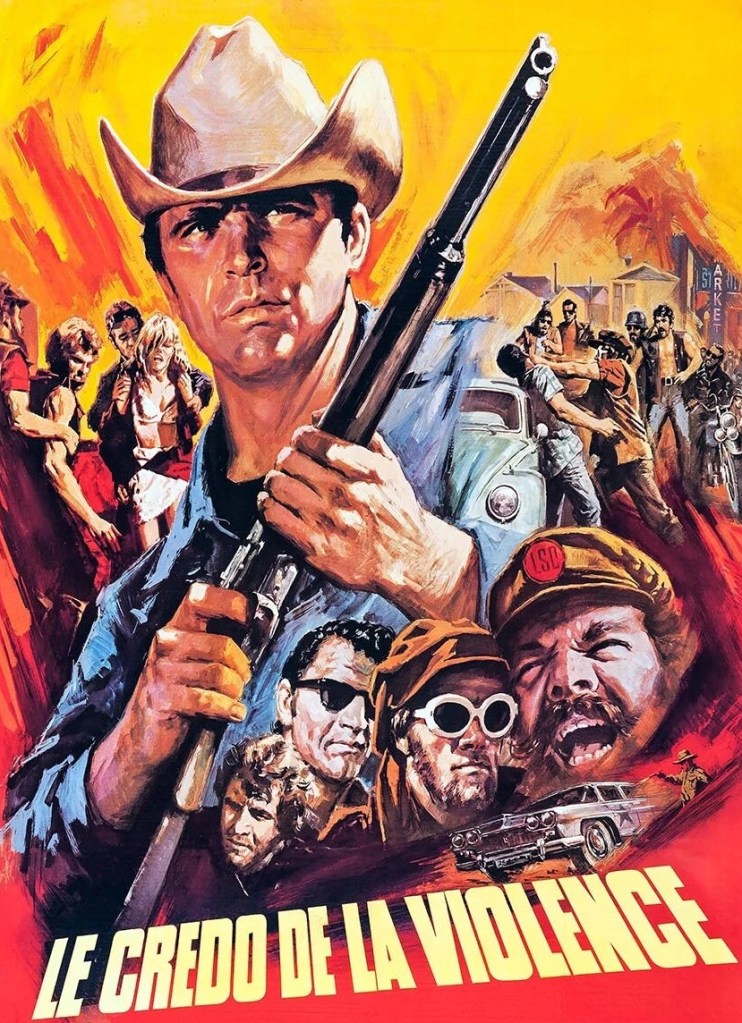

Nor is Billy Jack (Tom Laughlin) the kind of two-fisted vigilante protector of the underdog as exemplified by Clint Eastwood and Charles Bronson. In fact, where Eastwood and Bronson generally dodge judgement of their maverick style, Billy Jack gets into more trouble with the law for preventing a young man being beaten to death than the bikers attempting to beat the victim to death.

But unlike the Eastwood and Bronson vehicles, the actor Laughlin isn’t center stage all the time. And that’s primarily what makes the picture work. The director in Laughlin is very even-handed, covering the various aspects that produce a more than tolerable narrative and one that also reflected what would be a later Hollywood trope, the victims too frightened to come forward for fear of further retaliation.

There’s an unusually idyllic opening for a biker picture that telegraphs to the audience this going to be different, Billy Jack surviving with ease in the mountains and bathing under a waterfall. Likewise, Laughlin allows time to build up the two other main characters. Equally, unusually, they both have daddy issues. Wealthy Vicky (Elizabeth James) is devastated when her globe-trotting father fails to turn up for a long-promised rendezvous and biker leader Danny (Jeremy Slate) defies his bullying cop father, who spits in his son’s face. Whatever judgement you pass on the rest of Danny’s actions, he passes muster as a father, affectionately ruffling his son’s hair, and as a brother, standing up for his younger sibling.

You might also be surprised at the fashion statements. Vicky is decked out like Audrey Hepburn with those trademark sunglasses and is apt to take to the road on her two-wheeler wearing a white bikini. Danny wears an ironic version of the Hepburn shades. Whether Vicky’s ensemble is a deliberate attempt to draw comparison with Nancy Sinatra is anybody’s guess but the white boots the college girl wears are remarkably similar to the footwear in Sinatra’s most famous hit.

Once Billy Jack heads for the town, seeking work as a horse wrangler, he hits trouble in part due to overt racism, in part because he refuses to be a bystander when the authorities and citizens fail to act.

There’s an audacious jump-cut that would be the hallmark of more critically-acclaimed directors such as Tarantino, and a scene of bikers arriving over the hill that’s reminiscent of John Ford westerns. And there’s a hint of homosexuality.

Five rapes take place offstage, but their harrowing consequence is not passed over. Mental health is damaged beyond repair, LuAnn (Julie Cohn) afraid to show her face in public, while Vicky is treated as a freak. With the town boasting its “weakest sheriff” and the girls capitulating to intimidation, it’s left to Linda Prang (Susan Foster) to agree to go to court. Luann, though under police protection, is kidnapped, and the bikers capture Vicky and Billy Jack, both girls facing further rape.

There are three stunning twists. Vicky, rather than Billy Jack, saves the day, sacrificing herself to save the Native American. Linda confesses she wasn’t raped, but had gone of her own free will with the bikers before and after the rape charge, in order to spite her mother because the bikers were “everything you hate.” And once justice is done Billy Jack is mistakenly shot by the cops.

While Billy Jack occasionally intervenes, mostly he’s outnumbered and beaten up, so he doesn’t fit the same template as Eastwood and Bronson. And that’s also to the picture’s benefit. This isn’t about the male hero, but male shortcomings and female suffering.

While there’s no great acting, the story is decently-plotted and the emotional jigsaw knits together.

Worth a look, but not if you’re expecting a typical biker picture.