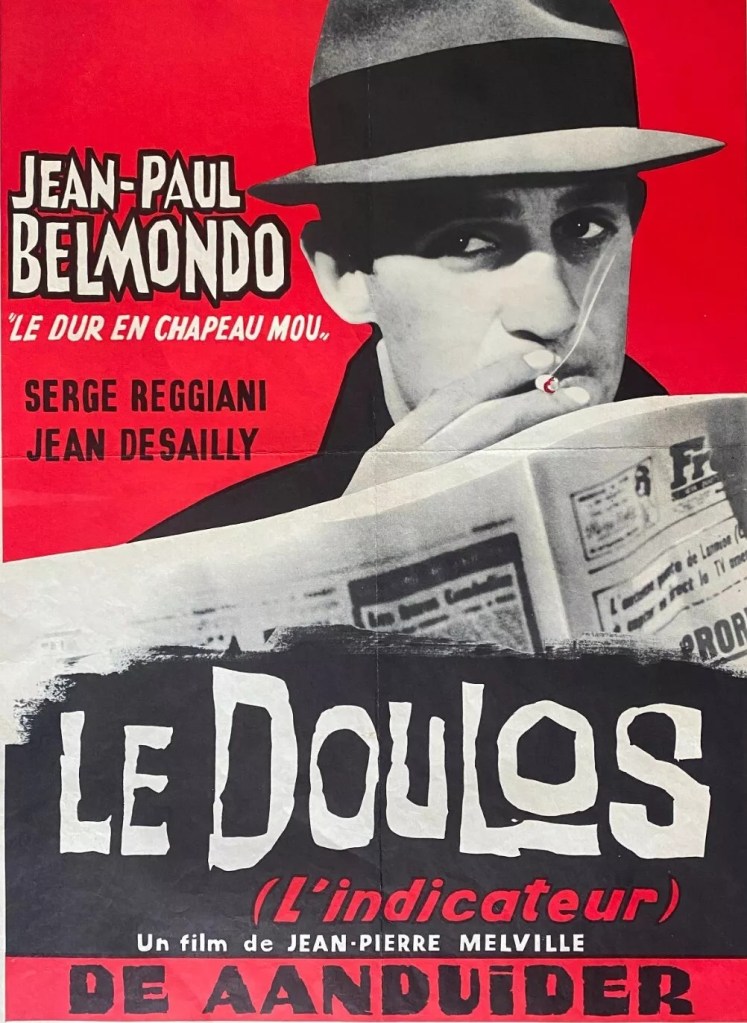

Stunning tour de force combining narrative complexity with technical audacity. Set up the template for later crime epics like Reservoir Dogs (1992) and The Usual Suspects (1995) and influenced Scorsese and Coppola. For the likes of me who revels in technical achievement, a delight, long tracking shots, two scenes over five minutes long shot in single takes, and rare use of the wipe. But technique is nothing without story. Luckily, here we are offered a riveting tale of double crossing, honor, revenge and that rare beast, irony. There’s a veritable tsunami of twists at the end but all the way through there’s the kind of sleight-of-hand that deserves a round of applause.

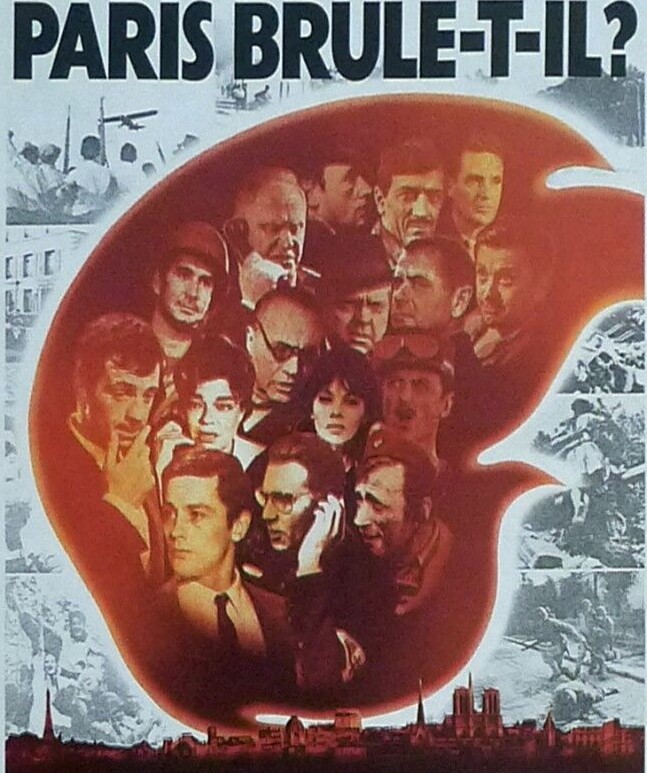

Jean-Pierre Melville hadn’t named his picture The Informer for the obvious reason of it being considered, erroneously, a remake of the John Ford 1935 Oscar-winning classic or just the danger of being unfavorably compared with it. But the pre-credit titles tell us that Le Doulos is underworld slang for an informer so we’re prepared for that element of the story. What we’re not prepared for is what comes next.

Maurice (Serge Reggiani), just out of prison after serving a six-year sentence, turns up at the house of fence Gilbert (Rene Lefevre) who’s helped him get back on his feet by setting him up with a safe-cracking job. Gilbert is appraising a cache of stolen jewels. Maurice shoots him, steals the jewels and a bundle of cash, burying the loot under a lamppost.

Maurice meets up with his partner Remy (Philippe Nahon) and another gangster Silien (Jean-Paul Belmondo), previously considered untrustworthy, who supplies the tools for the planned heist. While Maurice and Remy set off to burgle a house, Silien phones a cop, Inspector Salignari (Daniel Crohem). Silien viciously beats up Maurice’s girlfriend Therese (Monique Hennessey) and kills her.

The robbery doesn’t go according to plan, the cops turning up unexpectedly. In the shoot-out, Salignari and Remy are killed, Maurice wounded. Maurice passes on details of where he buried the loot to another buddy Jean (Philippe Marche).

Silien is picked up by the police as a known associate of Maurice. The interrogation scene, which lasts five or six minutes, is a piece of cinematic bravura. Shot in a single take the camera follows chief interrogator Clain (Jean Desailly) as he paces round the room, Silien only coming into view when the cop stops in front of him and asks him a question. While refusing to rat on Maurice, Silien agrees, under pressure from the cops who threaten to expose his drug racket, to phone around the various bars where Maurice might be holing up. This triggers another virtuoso piece of filmmaking as Melville employs the wipe. Maurice is located, reading a newspaper report on Therese’s death.

There follows another colossal technical achievement, Maurice interviewed in another long single take, this time the interrogator pacing in front of the prisoner. Maurice is jailed, where he shares a cell with an assassin.

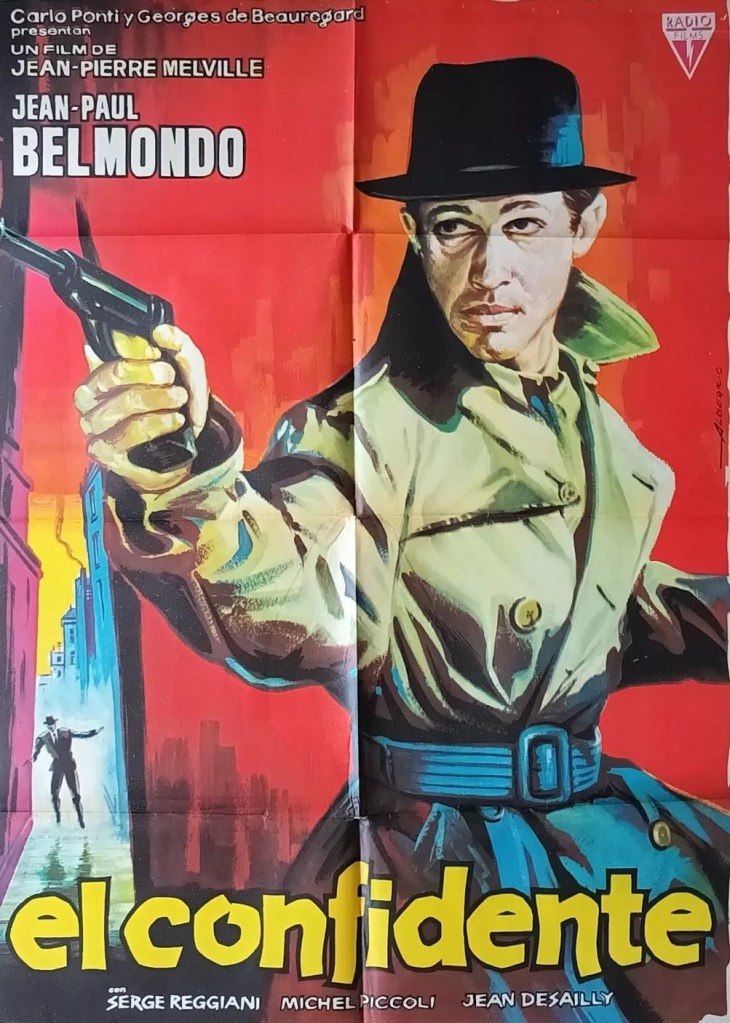

Meanwhile, Silien gets hold of the jewels and cash. He enrols old girlfriend Fabienne (Fabienne Dali), currently the unhappy squeeze of top gangster and club owner Nuttheccio (Michel Piccoli), and hatches a scheme that makes little sense to the audience. So we just have to watch. Silien breaks into Nutthecio’s club and in the guise of selling the gangster the jewels gets him to hold some of the items, thus, we quickly realize, covering them with his fingerprints.

Silien kills Nuttheccio then waits for the club-owner’s partner Armand (Jacques de Leon) to arrive, kills him and stages the scene to look like they killed each other over the jewels which he deposits in the safe. One of the jewels was found at the failed robbery so that’s enough to free Maurice.

Then we play out the revelation, the same kind of scenario repeated in The Usual Suspects, where the audience learns the truth. Therese was the snitch. That’s why she was killed. Gilbert was shot by Maurice because the dealer in stolen goods had drowned Maurice’s previous girlfriend Arletty. Even though you could argue that was justified, Maurice not being a good judge of character and not aware, as Gilbert was, that Arletty was also a police informer.

It was pure coincidence that Silien phoned Salignari on the night of the burglary. Despite being on opposite sides of the law, they were friends and the gangster was merely inviting the cop to dinner.

Silien proves to be such a straight-up guy that he hands all the stolen cash to Maurice. Silien plans to get out of the business and retire with Fabienne to a house in the country. Then we learn that Maurice has distrusted Silien after all and arranged for the assassin he met in jail to kill Silien. To try and prevent that, he races to the country house, fortuitously arriving before Silien and is, ironically, shot by the assassin. When Silien arrives shortly afterwards he, with more savage irony, is also despatched.

I watched this initially thinking what a huge risk Jean-Paul Belmondo (Borsalino, 1970) was taking in playing, as I initially believed, not just a police informer, but stealing from Maurice the buried loot and leading the police to him. It would have been a hell of a note if the narrative had continued in the same hard-nosed vein especially after Silien’s absolutely brutal treatment of Therese. The slap he administered came out of nowhere and resounded like a gunshot. He then tied her up, again venomously, and poured a bottle of whisky over her head.

That it turned out to be a story of honor among thieves was perhaps the biggest twist of all.

Jean-Paul Belmondo is outstanding in an underplayed role, Serge Reggiani (The Leopard, 1963) convincing as the two-timing crook.

Deservedly recognized as one of the most influential crime pictures of all time, this is nothing short of a masterpiece by Jean-Pierre Melville (Army of Shadows, 1969). Written by the director from the novel by Pierre Lesou.

Beg, borrow or steal this one.