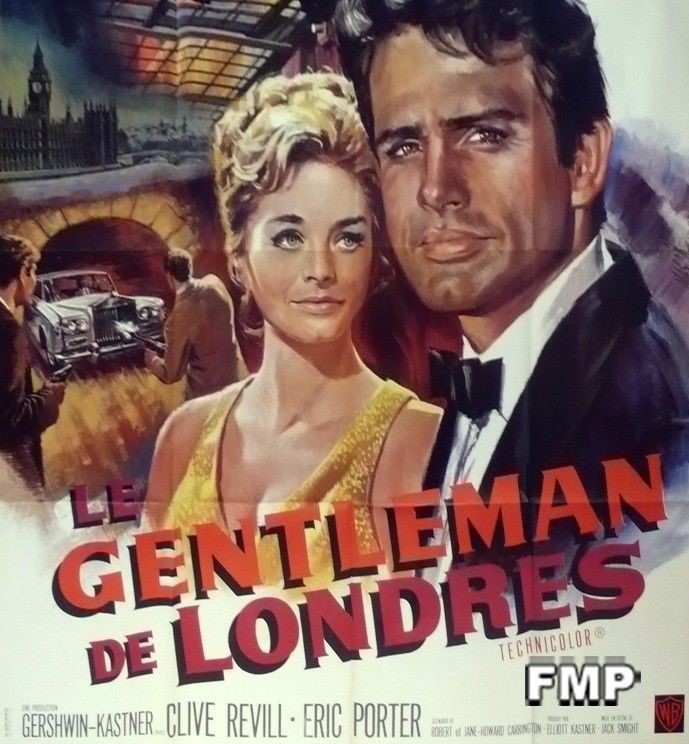

Amazing the tension that emanates from the turn of a card. Or, more correctly, waiting for one. Only problem is we’re two-third through the movie before high-stakes poker begins – the pot nudging £250,00 (close on a cool £5 million now). Mostly, the earlier tension derives from not knowing what the hell is going on in this enjoyable thriller made at the height of the Swinging Sixties as playboy gambler Barney (Warren Beatty), a walking Carnaby St model driving an Aston Martin DB5, tilts the odds dramatically in his favor.

Barney is a gambler but the problem with gambling is the odds. They can be against you too much. So Barney decides to turn himself into a burglar, the kind that can clamber over rooftops, abseil between buildings, and break into – a printing business called Kaleidoscope. This just happens to print the playing cards supplied to all the major European casinos. So Barney does a little doctoring of the master printing plates. Bingo, the odds are a bit more even now that he knows what cards are coming out of the shoe – he plays chemin de fer (as it is known in posh casinos, pontoon or 21 to you and me).

While cleaning up he bumps again into fashion designer Angel (Susannah York) – their original meet-cute taking place in a traffic jam – who he dated once in London. Unbeknownst to him, she is on a scouting mission, looking to snare the kind of high-rolling gambler who can take on and completely fleece the drugs kingpin Harry (Eric Porter) being pursued by cop Manny (Clive Revill), her father who, rather than waste so much time collecting the required evidence to put the villain behind bars, decides it would easier done by making him broke. Unable to pay his debts, some other villain would put him out of business in the traditional cemented-boot fashion.

It takes a while for the movie to line up all its ducks in a row, mainly by holding on to the information the audience requires. But the audience is privy to details of the way Manny works that Barney is not. Even for ruthless villains, Manny has a peculiar calling card, one that would make any gambler think twice about entering his lair. Of course, it doesn’t take long for Manny to rumble Barney’s game so the stakes are much higher than the charming gambler imagines.

Throw in as much fashion as London was capable of generating at this time, the burgeoning romance, some exotic European locations, a castle with a moat, and the usual tourist guide stuff of red buses, Big Ben, Piccadilly Circus, pubs and Tower Bridge and you have all the ingredients of an easy on the eye thriller.

It’s a movie that relies on star power but Beatty and York deliver. That is, if you don’t need Beatty to do much more than be Beatty, all teeth and charm. At this point in his career Beatty looked as if his career was fast approaching its end. The box office success of Splendor in the Grass (1961) had been followed by a string of flops, romantic dramas and comedies that should have had audiences queuing up plus an occasional wild card like Arthur Penn’s Mickey One (1965), the biggest flop of all. He does make an engaging crook, and he never loses his screen charisma here, but there ain’t quite the right number of twists that moviegoers weaned on the likes of Topkapi (1964) had come to expect.

Hollywood had been doing its best to position Susannah York as a top box office attraction and she had snagged the female lead in The 7th Dawn (1964) opposite William Holden and Stanley Baker in Sands of the Kalahari (1965) but she was recovering from the colossal flop of Scruggs (1965) by ‘poet of the cinema’ David Hart. Kaleidoscope offered the kind of role York could do with her eyes closed. So while the screen pair were not exactly sleep-walking it was not the kind of story that was going to create sparks.

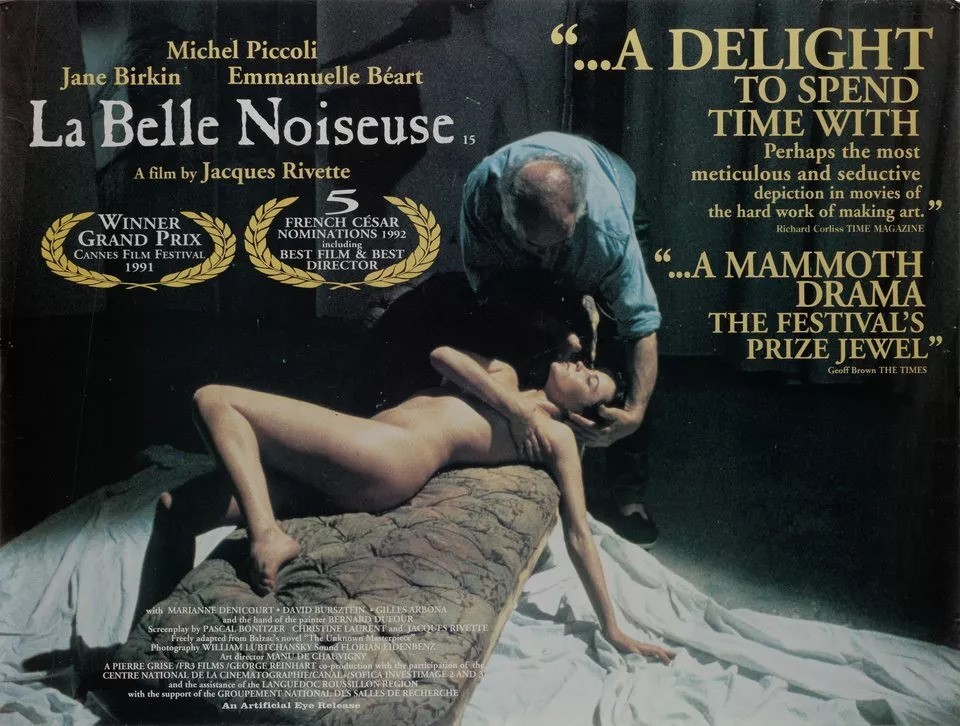

Character actor Clive Revill (Fathom, 1967) and Eric Portman (The Pumpkin Eater, 1964) take more leeway with their roles, the latter almost chewing he scenery, the former content with just chewing his lips. Look out for Jane Birkin (Blow-Up, 1966) and British television stalwarts Yootha Joyce, George Sewell and John Junkin.

The title would have been more enigmatic, original meaning of images twisted out of shape, had it not also applied, straightforwardly, to the card-making company. Giving Harry the surname of Dominion seems overkill.

Director Jack Smight (No Way to Treat a Lady, 1969) came to this after twisty private eye picture Harper/The Moving Target (1966), a big hit starring Paul Newman. This is too lightweight a feature to command such interest, but he does keep the story rolling along and it’s an effortless watch and it has a certain offbeat quality. The screenplay was fashioned by Robert Harrington and Jane-Howard Harrington, making their movie debut, who also co-wrote Wait until Dark (1967). It was also the debut for Winkast Productions, the Jerry Gershwin-Elliott Kastner production team who went on to make Where Eagles Dare (1968).