As if John Wayne hadn’t endured enough directing The Alamo (1960), he took on an even weightier task with this Vietnam War picture which, from the start, was likely to receive a critical roasting given the actor’s well-known stance on the conflict and his anti-Communist views that dated back to the McCarthy Era of the 1950s. Wayne had enjoyed a charmed life at the box office with three successive hit westerns, Henry Hathaway’s The Sons of Katie Elder (1965) with Dean Martin, Burt Kennedy’s The War Wagon (1967) co-starring Kirk Douglas, and best of all from a critical and commercial standpoint Howard Hawks El Dorado (1967) pairing Robert Mitchum. Outside of box office grosses, Wayne’s movies tended to be more profitable than his box office rivals because they were generally more inexpensive to make.

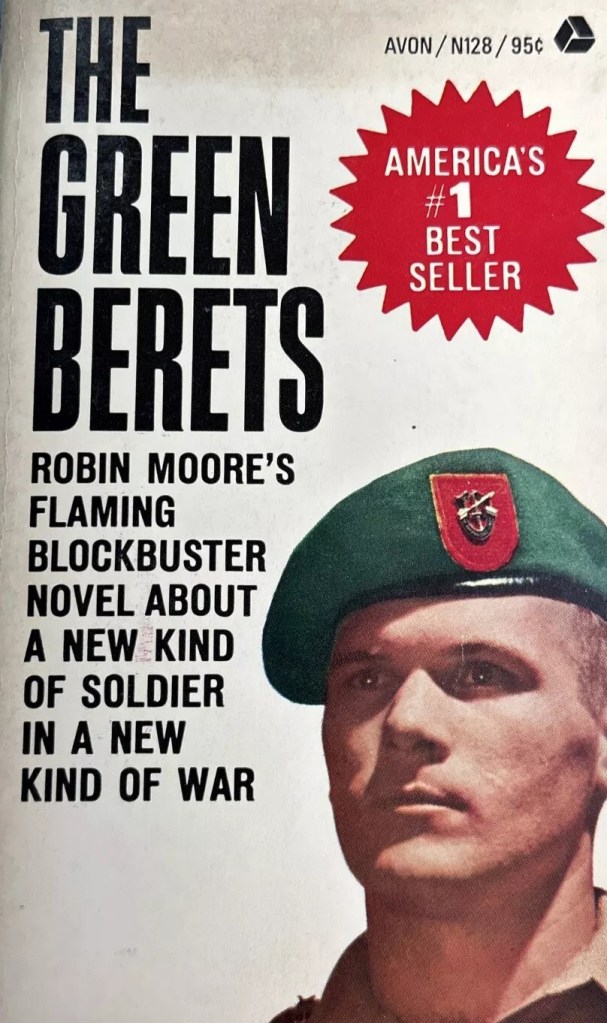

Columbia had been the first to recognize the potential of the book by Robin Moore and purchased the rights pre-publication in 1965 long before antipathy to the war reached its peak. A screenplay was commissioned from George Goodman who had served in the Special Forces the previous decade and was to to return to Vietnam on a research mission. But the studio couldn’t turn out a script that met the approval of the U.S. Army. Independent producer David Wolper (The Devil’s Brigade, 1968) was next to throw the dice but he couldn’t find the financing.

In 1966 Wayne took a trip to Vietnam and was impressed by what he saw. He bought the rights to the non-fiction book by Robin Moore (who also wrote The French Connection) for $35,000 plus a five per cent profit share. While the movie veered away in many places from the book, the honey trap and kidnapping of the general came from that source, although, ironically, that episode was entirely fictitious, originating in the mind of Robin Moore.

Universal originally agreed to back The Green Berets with filming scheduled for early 1967 but when it pulled out the project shifted to Warner Bros. And as if the director hadn’t learned his lesson from The Alamo, it was originally greenlit for a budget of $5.1 million, an amount that would prove signally inappropriate as the final count was $7 million. Wayne turned down the leading role in The Dirty Dozen (1967) to concentrate on this project. Wayne’s character was based on real-life Finnish Larry Thorne who had joined the Special Forces in Vietnam in 1963 and was reported missing in action in 1965 (his body was recovered four decades later).

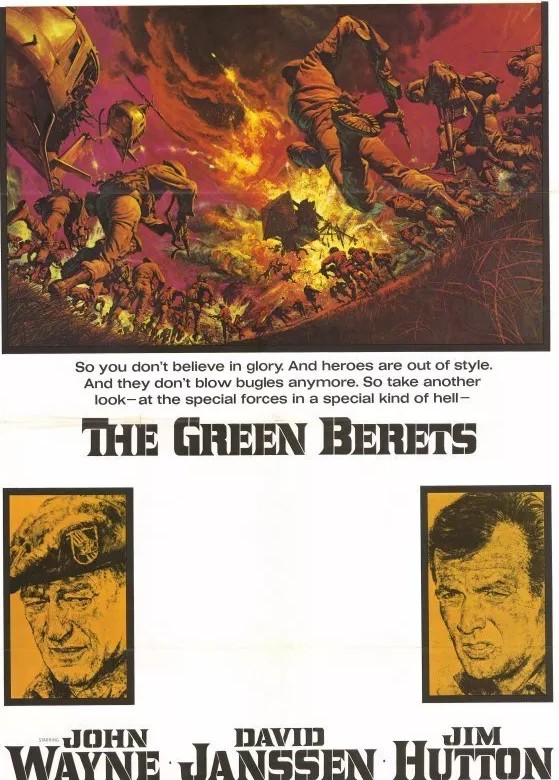

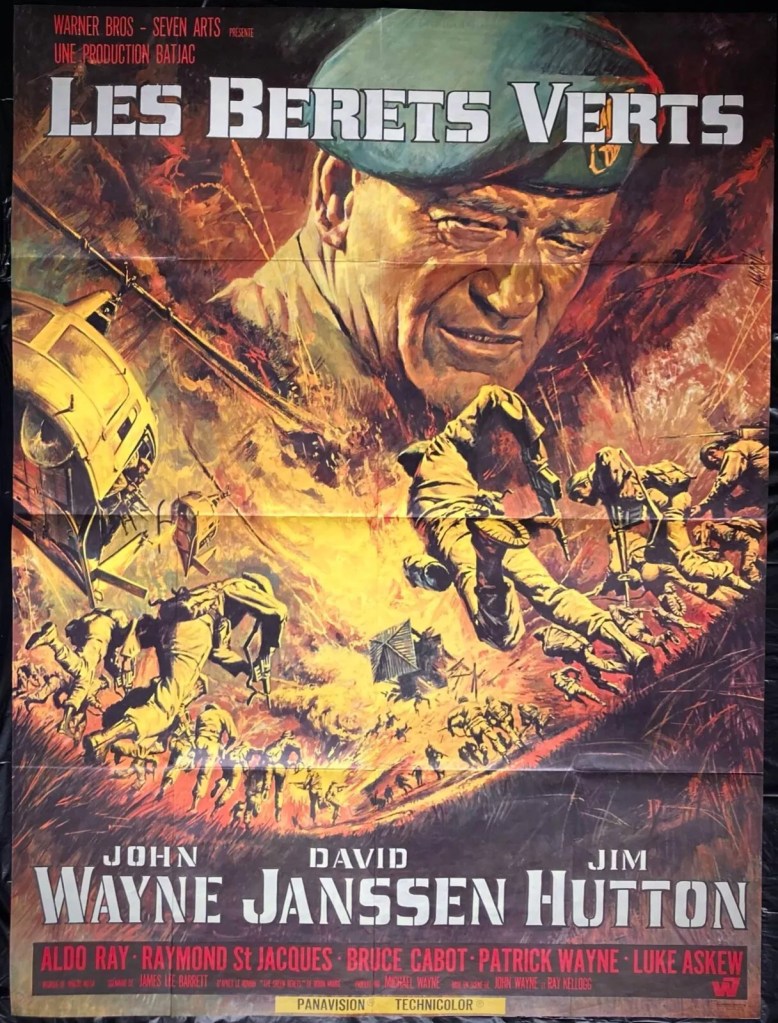

As well as John Wayne, the movie was a platform for rising stars like Jim Hutton (Walk, Don’t Run, 1966), David Janssen (Warning Shot, 1967) and Luke Askew (Easy Rider, 1969) who replaced Bruce Dern. Howard Keel, who had appeared in The War Wagon, turned down a role.

Wayne holstered his normal $750,000 fee for acting plus $120,000 for directing. But it turned out The Alamo had taught him one important lesson – not to shoulder too much of the responsibility – and Ray Kellogg for the modest sum of $40,000 was brought in as co-director. It was produced by Wayne’s production company, Batjac, now run by his son Michael. But neither Wayne nor Kellogg proved up to the task and concerned the movie was falling behind schedule and over budget the studio drafted in veteran director Mervyn Leroy – current remuneration $200,000 plus a percentage – whose over 40 years in the business ranged from gangster machine-gun fest Little Caesar (1931) to his most recent offering the Hitchcock-lite Moment to Moment (1966).

But exactly what LeRoy contributed over the next six months was open to question. Some reports had him directing all the scenes involving the star; others took the view that primarily he played the role of consultant, on set to offer advice. Even with his presence, the movie came in 18 days over schedule – 25 per cent longer than planned. Unlike the later Apocalypse Now (1979), it didn’t go anywhere near South-East Asia so the location didn’t add any of Coppola’s lush atmosphere, though the almost constant rain in Georgia, while a bugbear for the actors, helped authenticity.

It was filmed instead on five acres of Government land around Fort Benning, Georgia, hence pine forests rather than tropical trees. President Lyndon B. Johnson and the Department of Defense offered full cooperation. But that was only after the producers complied with Army stipulations regarding the screenplay. James Lee Barratt’s script was altered to show the Vietnamese involved in defending the camp and the kidnapped was switched from being over the border. Also axed, though this time by the studio, was Wayne’s wish for a romantic element – the studio preferred more action. Sheree North (Madigan, 1968) was offered the role of Wayne’s wife but she also turned it down on political grounds. Vera Miles (The Hellfighters, 1968) was cast but she was edited out prior to release.

The Army provided UH-1 Huey helicopters, the Air Force chipped in with C-130 Hercules transports, A-1 Skyraiders and the AC-47 Puff the Magic Dragon gunship and also the airplane that utilized the skyhook system. Actors and extras were kitted out in the correct jungle fatigues and uniforms. Making a cameo appearance was Col Welch, commander of the Army Airborne School at Ft Benning. The sequence of soldiers doing drill was actually airborne recruits.

The attack on the camp is based on the Battle of Nam Dong in 1964 when the defenders saw off a much bigger enemy unit.

This set was built on a hill inside Fort Benning. The authentic detail included barbed wire trenches and punji sticks plus the use of mortar fire. While the camp was destroyed during filming the other villages were later used for training exercises. .

The pressure told on the Duke physically – he lost 15lb. But the oppressive heat and weather of that location – it was mostly shot in summer 1967 – was nothing compared to the reviews. It was slated by the critics with Wayne’s age for an active commander called into question, never mind the parachuting, the gung-ho heroics and the dalliance in an upmarket nightclub.

“In terms of Wayne’s directorial career,” wrote his biographer Scott Eyman, “The Alamo has many defenders, The Green Berets has none.” That assessment, of course, would be to ignore the moviegoers around the world who bought tickets and put the picture into reasonable profit.

Wayne was clear in his own mind about the kind of movie – “about good against bad” – he was making and accommodated neither gray areas nor took note of current attitudes to the war as exemplified by nationwide demonstrations. Co-stars David Janssen, Jim Hutton and George Takei were opposed to the war. Takei, a regular on the Star Trek series, missed a third of the episodes on the second season; his lines were written to suit the character of Chekov, who went on to have a bigger role in the television series. Composer Elmer Bernstein turned down the gig as it went against his political beliefs. “The Ballad of the Green Berets,” heard over the opening credits was not composed for the film, having been released two years earlier.

Most critics hated it – “Truly monstrous ineptitude” (New York Times); “cliché-ridden throwback” (Hollywood Reporter); “immoral” (Glamour). Even those reviews that were mixed still came down hard: “rip-roaring Vietnam battle story…but certainly not an intellectual piece” (Motion Picture Exhibitor). Not that Wayne was too concerned. At the more vital place of judgement – the box office – it took in $9.5 million in rentals (what’s returned to the studios once cinemas have taken their cut) – $8.7 million on original release and a bit more in reissue – in the U.S. alone plus a good chunk overseas.

It was virtually impossible to examine a movie like this without taking a political stance. Other movies covering the same topic were allowed greater latitude regarding authenticity, audiences and critics like appearing to accept that creating watchable drama often took precedence over the facts. Both The Deer Hunter (1978) and Apocalypse Now, considered the best of this sub-genre, clearly ventured away from strict reality. With over half a century distancing the contemporary viewer from those inflammatory times, it’s worth noting that it still divides critics. Or, rather, critics and the general public take opposing views.

Although Rotten Tomatoes deems it “an exciting war film”, the critics voting on that platform gave it a lowly 23 per cent favourable report compared to a generally positive 61 per cent from the ordinary viewer. That contrasts, for example, with a more even split for the likes of Exodus (1960) – 63 per cent from critics and 69 per cent from audiences. However, The Green Berets attracts twice as much interest, collaring 9,000 votes compared to just 4,300 for Exodus.

After this, Wayne’s fee went up to a flat million bucks a picture. “He wasn’t a guarantee of success,” explained his son Michael, “he was a guarantee against failure.” At this point in his career, he was gold-plated. Where other stars in his commercial league suffered the occasional box office lapse – Paul Newman’s career in the 1960s, for example, was riddled with flops like The Secret War of Harry Frigg (1968) – he did not. Especially with a global following, his pictures never lost money.

SOURCES: Michael Munn, John Wayne, The Man Behind the Myth, Robson, 2004; Scott Eyman, John Wayne, The Life and Legend, Simon and Schuster, 2014; Brian Hannan, The Magnificent 60s, The 100 Top Films at the Box Office, McFarland, 2023; Robin Moore, Introduction, The Green Berets, 1999 edition, Skyhorse Publishing; Laurence H. Suid, Guts and Glory, University of Lexington Press, 2002; The Making of The Green Berets, 2020; Review, Hollywood Reporter, June 17, 1968; Review, Motion Picture Exhibitor, June 19, 1968; Renata Adler, “The Absolute End of the ‘Romance of War’”, New York Times, June 30, 1968; Glamour, October 1968; “Big Rental Pictures of 1968,” Variety, January 8, 1969.