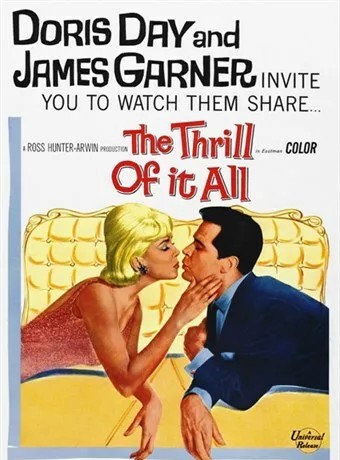

Has three unusual distinctions for a Doris Day comedy. First of all, it’s feminist. Secondly, it’s prophetic. Third, and perhaps most interesting of all, is that it plays exactly into expectations – for completely different reasons – for audiences sixty years apart. Only the ending would split the audiences.

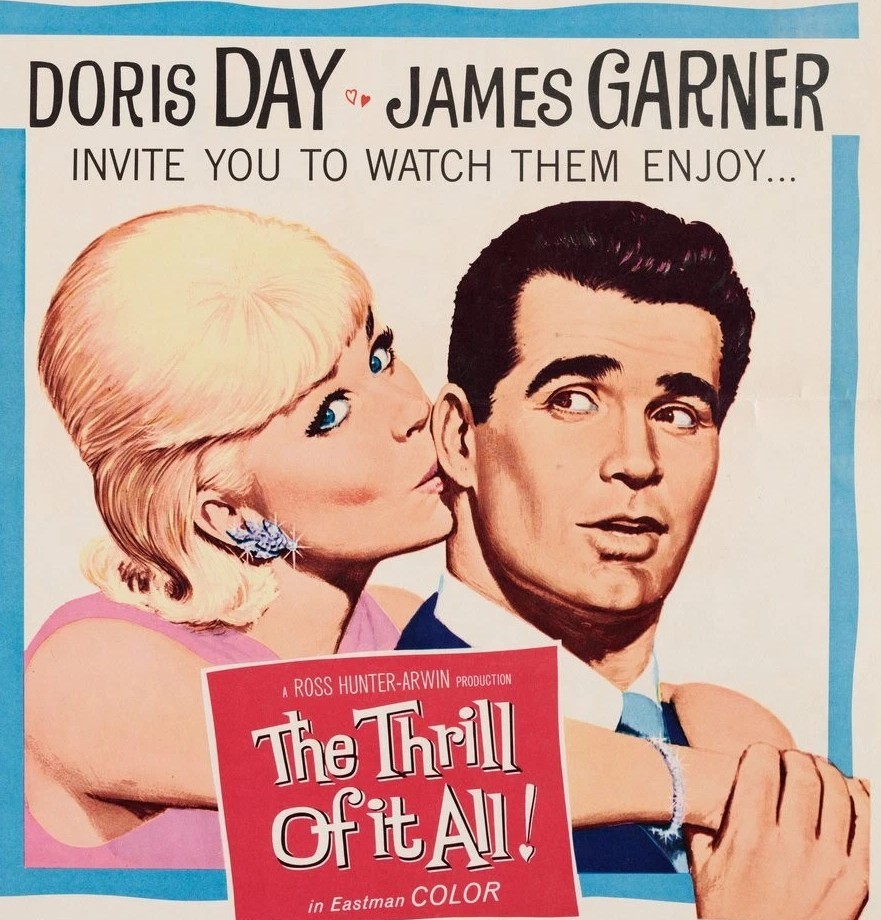

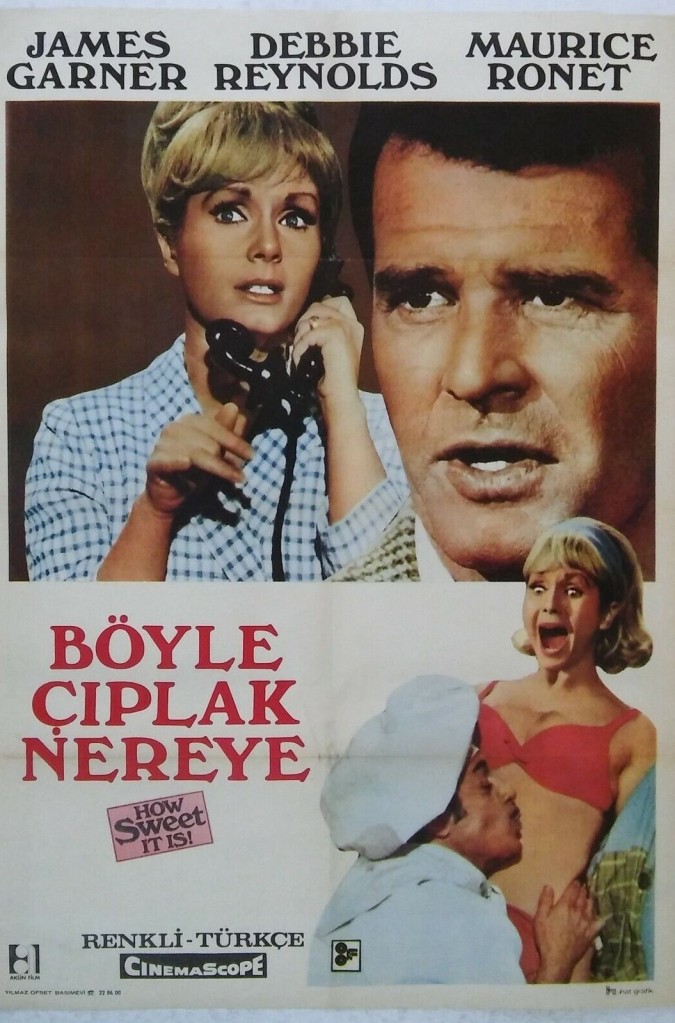

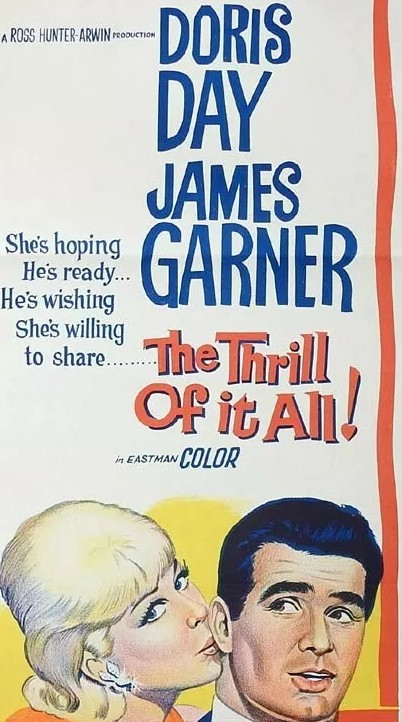

And this is a somewhat mature Doris Day. Having shucked off Rock Hudson and Cary Grant, she was no longer stuck in a relatively mindless, however charming, love story following the usual formula of girl-meets-boy girl-loses-boy girl-gets-boy. Here she’s contented housewife Beverly Boyer married to successful obstetrician Dr Gerald Boyer (James Garner) with two kids apt to cause disruption but whose main purpose, equally unusually, is to make caustic comment about grown-up behavior. There is one magnificent outlandish set-piece involving soap powder but the slapstick is toned down and there’s a gentle satire of the television industry and advertising.

There’s only one downside to the marriage, her husband is being called out at all hours to deliver babies and that’s such a worthy calling what decent wife could complain about such absences even if it means spoiled dinners and missing events.

However, everything is turned upside down when by pure chance Beverly takes on the role of becoming the onscreen spokesperson for a brand of soap called Happy Soap. This being in the days of live television – so this is set strictly in the 1950s hence the more pronounced tone of a woman’s place being in the home – she has to do the advertisement live on air and her fumbling and inexperience touch a chord with audiences who respond with such vigor that she is offered a contract that puts her in the position of earning substantially more than her husband. How dare she?

Naturally, the demands placed upon her by the advertising company turns the domestic tables. She’s the one coming home late and he’s the one seen as her adjunct. The soap powder boss is so determined to keep her he fulfills every whim – even when such wishes are not made with any seriousness. So she wakes up one morning with a swimming pool in the back yard which virtually demands that a car drive straight into it.

The battle of the sexes comes down a battle of women’s rights (yes, they are mentioned) against men’s rights, in other words freedom vs toeing the line. Rather than delighted at her extra dough, he’s infuriated that she’s infringing on his perceived role as being the sole provider for the family.

Eventually, he decides the only way to bring her to her senses is to arouse her jealousy by being seen in the company of other women. But that only works up to a point. And she only gives in when she is made to realize – by the only narrative misstep as far as the contemporary audience is concerned – that his job is much more important than hers.

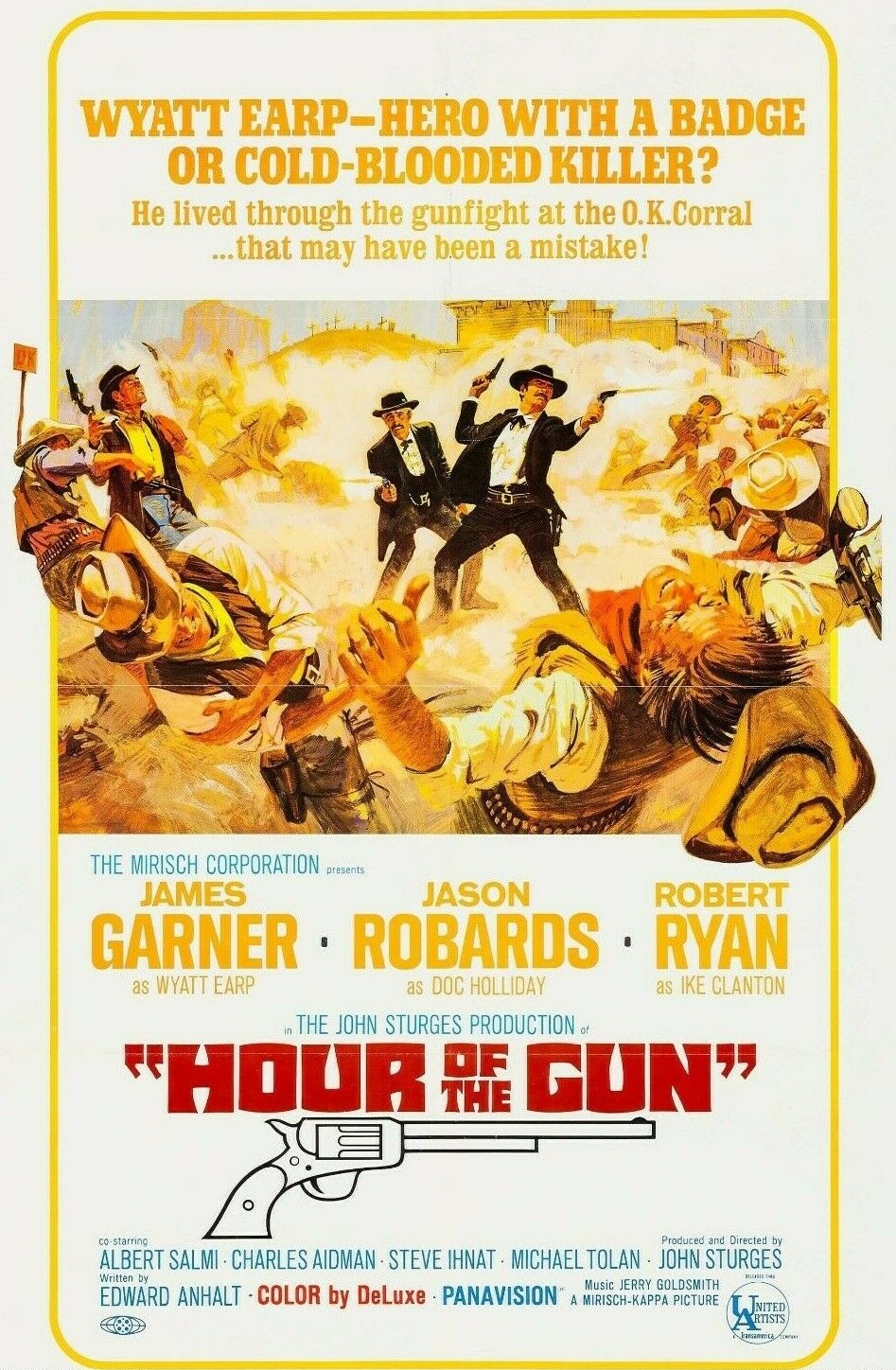

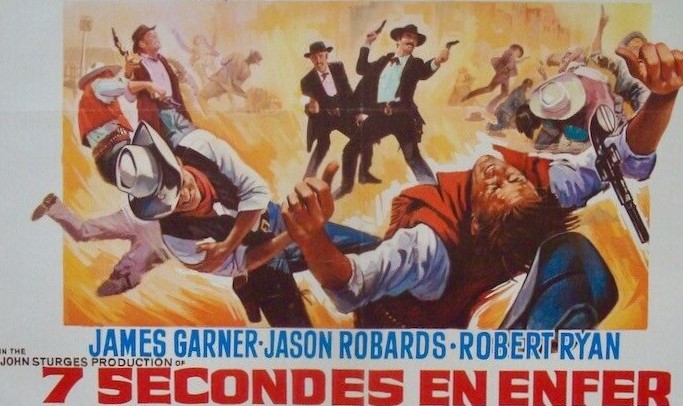

While this is the first of two pairings – the other being Move Over, Darling the same year – between Doris Day and James Garner (Hour of the Gun, 1967) is lacks the purer screen chemistry she found with Cary Grant and Rock Hudson and you feel the plot has been written to accommodate this deficit. There’s little requirement for intimacy or proper wooing, much less for the misunderstandings that fueled the previous pairings.

Doris Day’s haplessness is put to a different use, as it is initially the reason why she proves so appealing to television audiences.

Whether women in the 1960s had to keep to themselves their rooting for the career women in Beverly being given a chance to shine, or whether – the beginnings of the modern feminist movement dating from the publication of The Feminine Mystique by Betty Friedan published in 1963 – she was seen as a poster girl for the movement I’m not qualified to judge.

These days, however, Beverly would be viewed as an early champion of women’s rights and that, regardless of how important it was that a man tasked with delivering babies had a woman at home to make his dinner and mop his brow, his demands should not take priority.

While there aren’t as many outright laffs as in previous Doris Day comedies, the feminist angle provides the picture with an unusual worthiness, not something you’d go looking for in Day’s portfolio.

Directed by Norman Jewison (The Thomas Crown Affair, 1968) and written by Carl Reiner (The Art of Love, 1965).

Passage of time has made this more important than the material might suggest. Gets extra marks for serious intent.