Red faces all round. Uneasy pirate spoof that misses all its targets, coming close to resembling the kind of movie that gives turkeys a bad name and saved only by a spirited performance by Genevieve Bujold. Uber-producers Jennings Lang (Rollercoaster, 1977) and Elliott Kastner (Where Eagles Dare, 1968) should have known better but were seduced by the tantalizing returns for Richard Donner’s The Three Musketeers (1974) and its sequel which had revived the moribund swashbuckling genre.

Robert Shaw (Custer of the West, 1967) was nailed-on for the leading role since had made his name playing a pirate in British television series The Buccaneers (1956-1957) and was as hot as he was going to get after the double whammy of The Sting (1973) and Jaws (1975). However, the movie takes its cue from one of the chief supporting actors Major Folly (Beau Bridges).

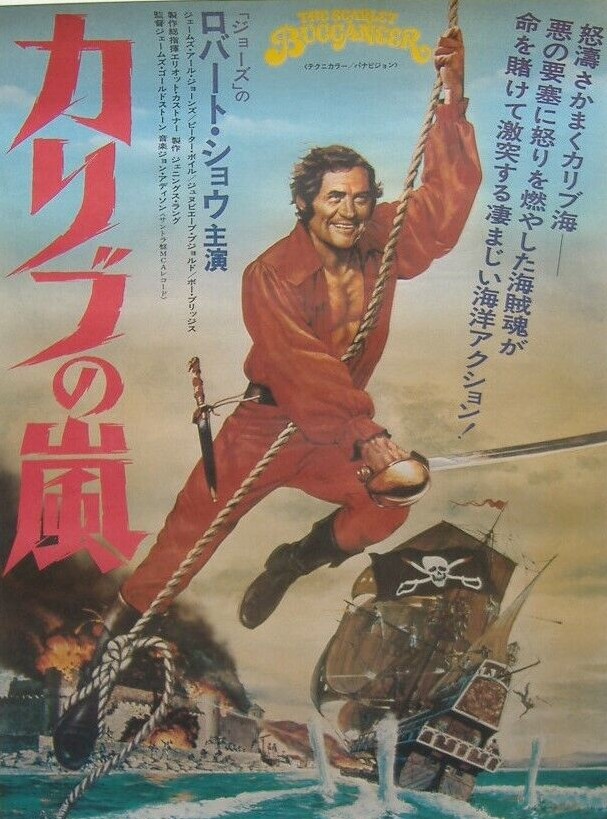

It’s color-coded. In case we can’t tell a good guy from a bad guy, we’ve got the Man in Red, pirate Ned Lynch (Robert Shaw), shaping up against the Man in Black, unscrupulous Jamaican governor Lord Durant (Peter Boyle). Ned is presented as a seagoing Robin Hood, Durant as the wicked Sheriff of Nottingham, his ruthlessness somewhat undermined by his predilection for playing with toy boats in his bath and for getting his hairy back waxed.

Twin narratives quickly unspool. Ned rescues from being hanged shipmate Nick Debrett (James Earl Jones) while Durant jails island chief justice Sir James Barnet (Bernard Behrens) and steals his treasure.

Stolen treasure being fair game, Ned and Nick hijack a coach-load of it, while Sir James’s on-the-run daughter Jane (Genevieve Bujold) ends up in their hands. Not being as black-hearted as his nemesis, Ned puts Jane ashore, but still a bit black-hearted humiliates her in a swordfight, and is disinclined to help her save her imprisoned father.

However, Jane has a trump card. For reasons unknown, Durant is heading back to England with a cargo of 10,000 dubloons, too tempting a target for any pirate. Naturally, nothing goes as planned but, as you might expect, there is a happy ending.

This might have worked, since all the ingredients are there, the laughing cavalier, the spirited woman, the humorous sidekick, the unprincipled villain. You’ve got an historically-accurate pirate ship for once, unlikely romance between high-born woman and charming scallywag, simple rescue-imprisonment-rescue scenario, and ample scope for swordplay.

Except the dialog is awful, the ship too small to accommodate any fighting so the pirates are landlubbers for the most part, and except for the duels between Ned and Jane and Ned and Durant, the swordfights are all kind of bundled together, and every now and then the action stops so we can hear a verse or two of a sea shanty sung by nobody in particular.

Though Ned and Nick trade cringeworthy, and in one case downright offensive, limericks, the best (only) laugh comes when Ned chucks Jane off a roof onto a canopy and follows up with the line “It worked.” It doesn’t help that Durant’s pederastic tendences are played as a joke. Everywhere you look people are turning cartwheels or are “blithering idiots” or “pawns” and as you might expect there’s a cat-fight and a monkey around to relieve a jailer of his keys. You are just praying for a shark to come along to put the cast out of their misery.

In the midst of this feast of over-acting along comes Genevieve Bujold (Anne of the Thousand Days, 1969) who must think she’s in a different picture. She is a feisty one all right, not above putting a knife to a man’s cojones, or kneeing them in that region, and, given the lawless state of the island, branded a criminal for wounding a rapist. At least she takes the whole thing seriously rather than as if being in a Mel Brooks picture.

It’s hard to know who to blame: the stars for acting as if enjoying a holiday from more serious fare; director James Goldstone (Winning, 1969) for failing to get the recipe right and employing a jaunty score that undercut everything, or writers Jeffrey Bloom (11 Harrowhouse, 1974) and Paul Wheeler (Caravan to Vaccares, 1974) for making a mess of the ingredients in the first place.

Of course, I am hardly blameless in drawing your attention to this, a sudden enthusiasm for pirate pictures sending me dashing into the wrong decade.

Watch for: Robert Shaw making a bid for the all-time Golden Raspberry; an unrecognizable Peter Boyle (Taxi Driver, 1976); Beau Bridges (Gaily, Gaily, 1969) doing his best Frankie Howerd impression; James Earl Jones (The Comedians, 1967) sounding normal, minus the deep-throated vocal tic on which he made his name; and so many inanities it falls easily into the So Bad It’s Good category.