A drunk falls into a swimming pool in the middle of the night and drowns. He has already crashed his car into the gate post of the villa. There’s no sign of foul play. No sign of the fact that his attempts to clamber out are hindered by someone holding his head down under the water until he loses consciousness.

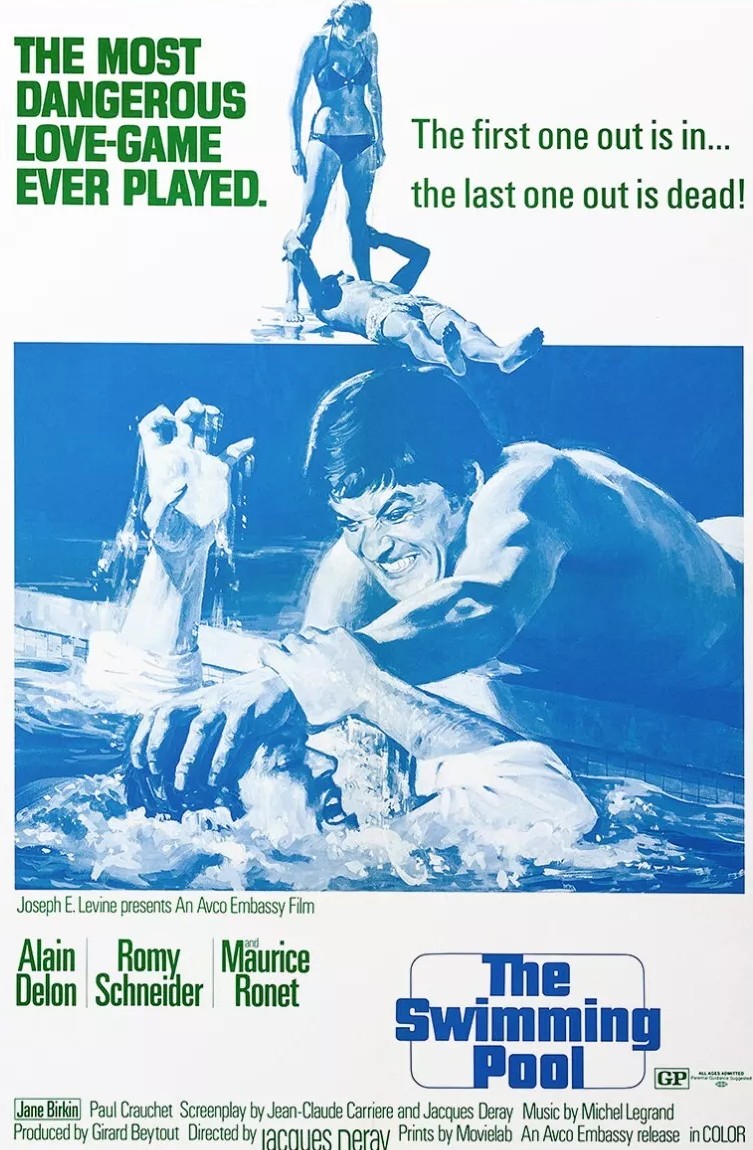

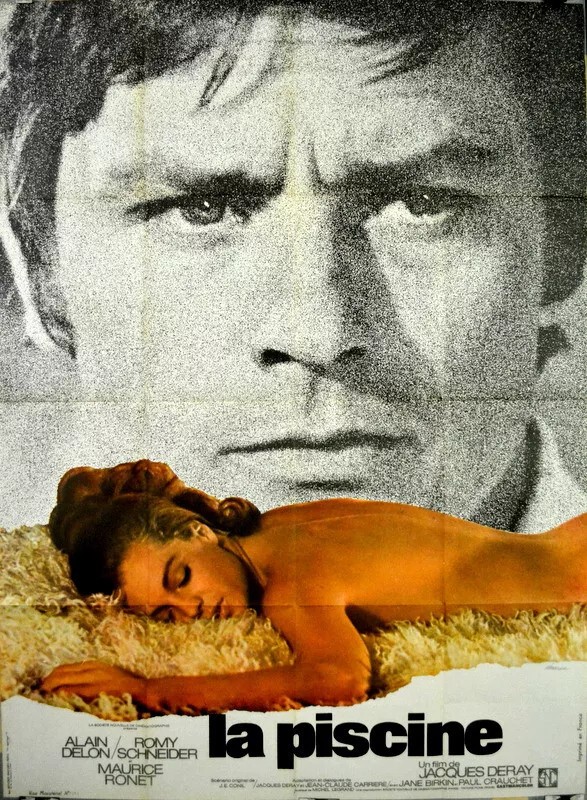

The perfect murder? Well, no, actually, because in the aftermath of the murder, recovering alcoholic killer Jean-Paul (Alain Delon) does about the dumbest thing you’ve ever seen. And that significantly detracts from what otherwise is a superb examination of sexual tension and hidden secrets.

So instead of leaving the corpse of best friend Harry (Maurice Ronet) floating fully clothed in the titular pool, Jean-Paul decides it would look better if it appeared that Harry had foolishly gone for a late night swim. So he pulls the dead guy out, strips off his clothes and decks him out in swimming trunks and slides him back into the watery grave.

He hides the sodden clothes somewhere and at the side of the pool puts a small stack of fresh clothes stolen from Harry’s wardrobe – he was a guest at the villa. But for some reason in pulling off Harry’s shirt he omits to remove his expensive watch which isn’t waterproof. Inspector Leveque’s (Paul Crauchet) suspicions are aroused by that simple fact. Although, theoretically, Harry might have been too drunk to notice, even though, obviously, the watch strap and the bulky watch would have caught on his shirt sleeve as he was taking off the item of clothing.

So the cop, in examining the clothes, is mightily surprised to discover they are fresh, unworn, not a sign of sweat or crumpled-ness, which is odd given Harry had been out dancing and enjoying himself for hours.

Psychologically, most of the aftermath is not just whether the cold-blooded killer – the otherwise very handsome, relatively charming writer Jean-Paul – will get away with it but whether his girlfriend Marianne (Romy Scheider), who has her own suspicions, will stand by him.

They have enjoyed a very intense sexual relationship and she clearly adores him. But she’s also the ex-lover of Harry and when Jean-Paul’s old pal, who is decidedly smooth with the ladies, turns up, the old sexual jealousy is rekindled. Either to get revenge or because he’s in any case that way inclined Jean-Paul has been making discreet moves on Harry’s eighteen-year-old daughter Penelope (Jane Birkin) who clearly despises her father.

We discover that Jean-Paul owes a great deal of his success to Harry who nurtured him through a severe depression that ended in attempted suicide. Rather than making Jean-Paul eternally grateful, it’s turned him into a spoiled brat, focused primarily on his own needs and without a loyal bone in his body when it comes to women.

For quite a while it looks like record producer Harry is going to steal away Marianne, if only for a brief affair, as Jean-Paul gives in to the sulks. But since Jean-Paul is already eyeing up Penelope, you would have thought any slip by Marianne would provide him with justification.

The murder is spur-of-the-moment. Jean-Paul has been drinking again and when Harry turns up drunk and launches into an attack on Jean-Paul’s character and hidden past, that’s when he ends up in the pool. Every time he tries to get out, Jean-Paul pushes him back in and eventually holds his head down underwater.

And he might have got away with the perfect murder except for stripping the body and forgetting about the watch, but when he decides to end his relationship with Marianne, the focus switches to whether she will betray him or not. There are a couple of twists on that score at the end.

So severely flawed psychological thriller. I’m guessing you could argue that anyone who kills someone out of the blue could easily be suffering from the kind of brain overload that prevents him thinking straight, but I didn’t fall for it. It would have been as easy to continue with the psychological stuff enough with Marianne maybe finding the wet clothes and facing the same choices that she eventually does.

What does elevate it are the performances. Austrian actress Romy Scheider (Otley, 1969), who had previously had an affair with Delon, is superb as a woman not sure if she has any principles given she is so easily in the thrall of attractive men. Although Alain Delon (Le Samourai, 1967) had played bad guys and immoral sorts before, this still feels like a fresh approach, the watchful, withdrawn calculating killer masquerading as something else.

Maurice Ronet (Lost Command, 1966) and Jane Birkin (Blow-Up, 1966) make significant contributions.

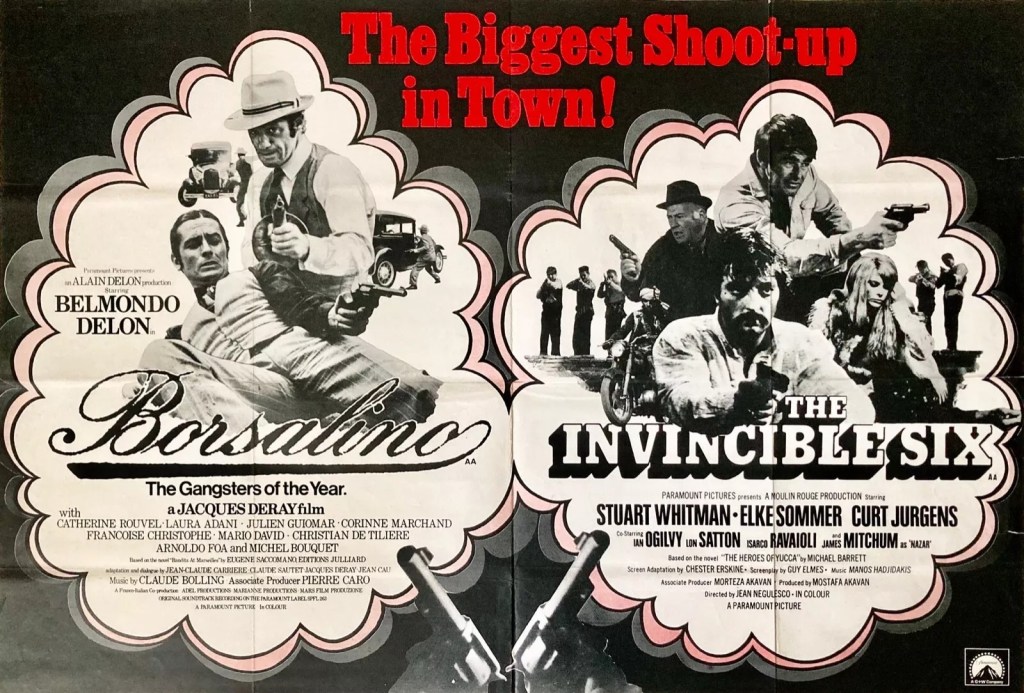

And director Jacques Deray (Borsalino, 1970) would have turned out another masterpiece had the movie not stumbled over the oddness of the murder. Written by the director, Alain Page (in his debut) and Jean-Claude Carriere (Viva Maria!, 1965).

Excepting the murder mishmash, superb.