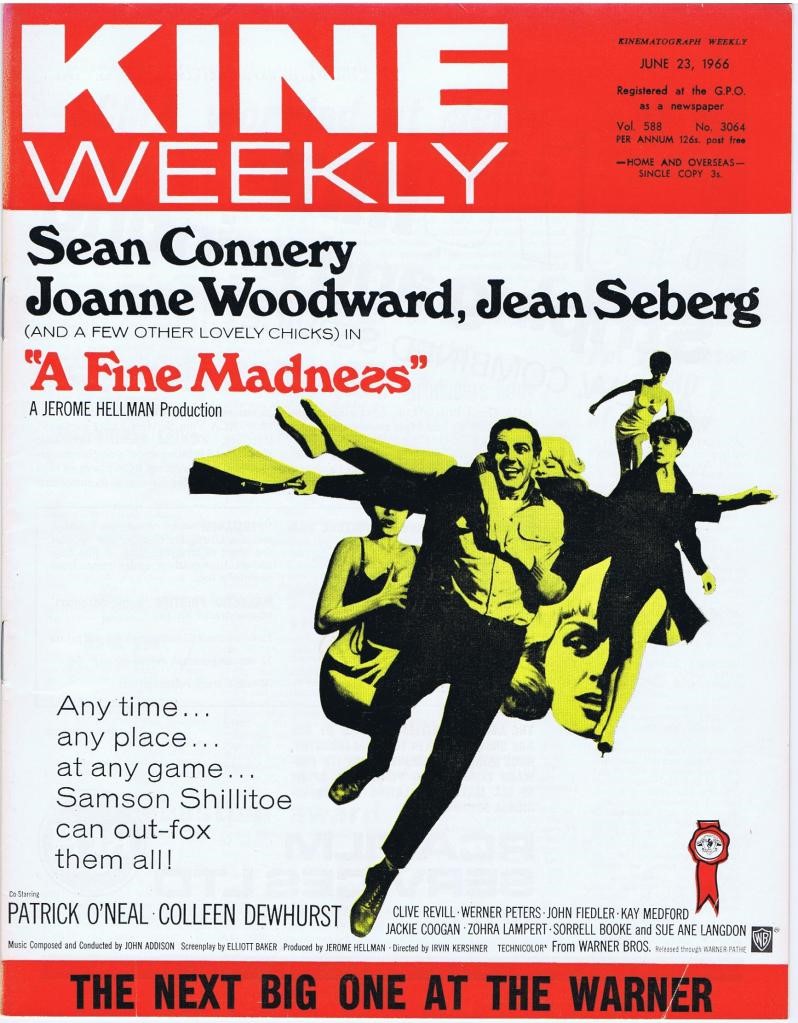

Let’s start with the Hollywood happy ending. Poet Samson (Sean Connery) slugs pregnant second wife (Joanne Woodward). He’d have punched her lights out before if only she hadn’t been so good at diving out of the way. As it is he manages to throw her down the stairs. The film kicks off with him ill-temperedly whacking her over the head with a pillow.

This is the kind of film where violence against women is treated as a running gag.

Lydia (Jean Seberg), wife of psychiatrist Dr West (Patrick O’Neal) treating Samson for writer’s block, doesn’t have the courage to make it plain to his creepy colleague Dr Vorbeck (Werner Peters) that she doesn’t fancy him when he endlessly paws her and slaps her rear so he takes this as the green light to attempt to rape her. That’s another running gag.

Surly loud-mouthed bully Samson gets a free pass because he’s an artist, a poet with one poor-selling volume of poetry, and unable to find the time or space to complete his masterpiece. He would have more time if he didn’t spend so much of it chasing women.

At my count, he gets through at least four – Lydia, office secretary Miss Walnicki (Sue Ann Lngdon), a client (he cleans carpets for a living) Evelyn (Zohra Lampert), and Dr Kropotkin (Collen Dewhurst), another colleague of Dr West, not to mention the current wife he drives demented and the previous wife for whom he is being aggressively pursued for alimony.

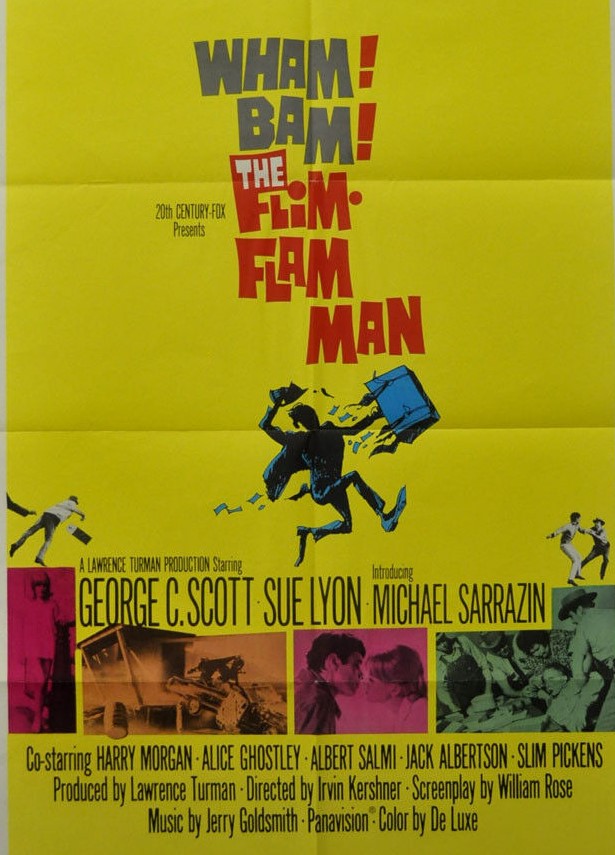

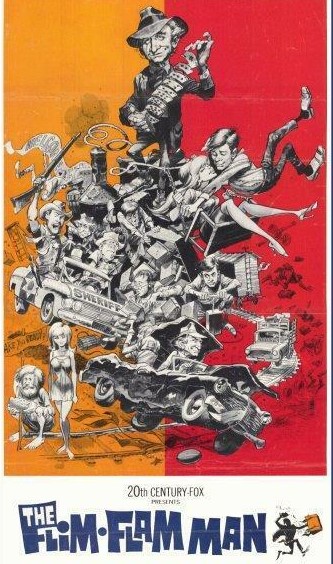

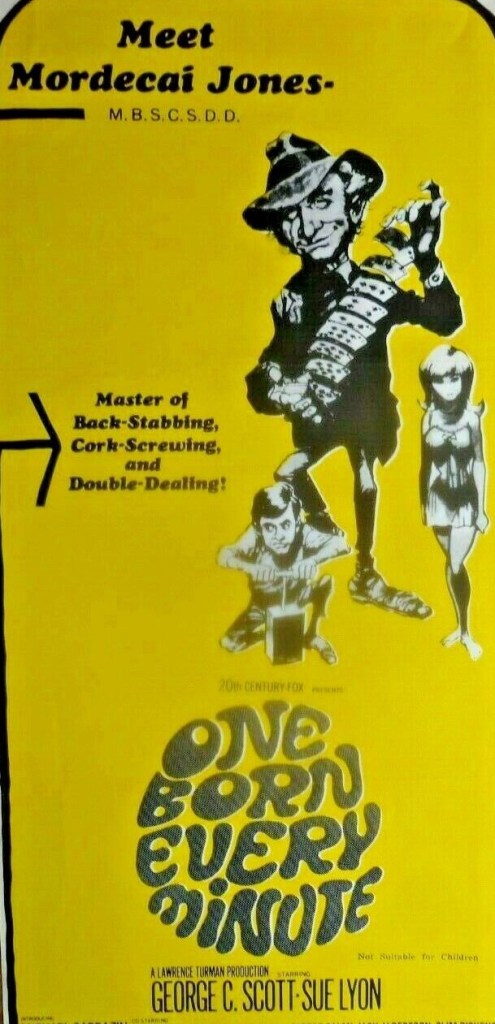

You can see how director Irvin Kershner was a shoo-in for The Flim-Flam Man/One Born Every Minute (1967) because at every opportunity he tries to turn simple dramatic confrontation that enhance the story into needless chases that divert it and extract slapstick from material that in no way suggests it’s ripe for such an approach.

There’s a story in here somewhere and a pretty barmy one at that if you set aside the poor poet’s endless battle against a world that fails to understand his genius and his dodging of the alimony. Rightfully diagnosed as some kind of sociopath by yet another of Dr West’s colleagues, the needle-happy Dr Menken (Clive Revill), he is admitted to a psychiatric hospital initially as a way of dodging his creditors and providing him with space and time to write.

Again, his most creative use of his time is to make out with Lydia and Krokoptin. But since he is spotted in a hydro-bath/ripple bath with naked Lydia, the vengeful husband gives the go-ahead to perform some kind of lobotomy on the poet, on the assumption it will dull his violent tendencies. (It doesn’t work.) The opportunity to satirise the psychiatric profession takes second place to another opportunity for a chase.

Anomalies abound. Samson’s character is clearly drawn on Welsh poet Dylan Thomas who exploited his fame and made his money on recital tours. Performing is against the broke Samson’s principles and he turns viciously on his audience of appreciative women. Despite demanding center stage, when offered it he turns it down. He lambasts middle-aged women but has little against those younger members of the species more susceptible to his charms. He only has to tell Miss Walnicki she has “pouty lips” and she falls into his arms.

All this has going for it are the performances. Sean Connery (Marnie, 1964), it has to be said, certainly exhibits screen charisma though this is not as far removed as he would like from the macho James Bond. Joanne Woodward (From the Terrace, 1960) – switching from her normal brunette to blonde – is excellent as the downtrodden waitress wife, but on the occasions when she is spiky enough to put him in his place soon regrets her temerity.

Jean Seberg (Pendulum, 1969) – switching from blonde to brunette and paid more ($125,000 to Woodward’s $100,000) – is good as the sexually frustrated rich housewife. And Patrick O’Neal (Stiletto, 1969) looks as if he is desperate to throw a punch. Elliott Baker (Luv, 1967) wrote the screenplay based on his own novel.

You do sometimes wonder at the knuckle-headedness of stars. Was this all that was offered to Connery at his James Bond peak? Or was it a pet project? I doubt if it would have been made with another big star – you couldn’t see even the macho Steve McQueen entering this territory and the likes of Paul Newman wouldn’t go near it.

Theoretically, studio head honcho Jack Warner gets the blame for this. He didn’t like Kershner’s cut and ordered it re-edited but I’d be hard put to see how his hand could be any less heavy than that of the director.

That’s two stinkers in a week. If you want proof of just how rampant sexism was in Hollywood check out a double bill of this and A Guide to a Married Man (1967).

An insult.