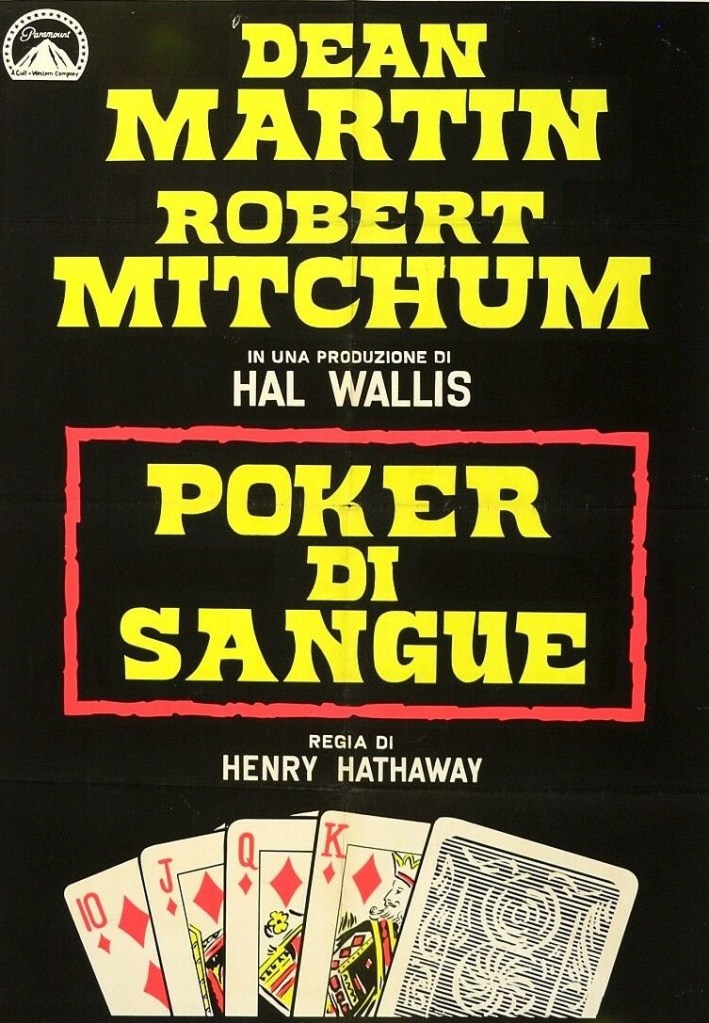

Another western in sore need of re-evaluation. Largely dismissed as a routine oater trading on the gimmick of a whodunit and packed with old stagers, this is in fact about a serial killer, a treatise on law and order, and almost acts as a conduit between the decade’s previous westerns when the good guys and the bad guys are easily defined to the end of the decade when such distinctions were muddied after The Wild Bunch (1969) and Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969) invited audiences to root for the bad guys. In this rather well-structured picture, full of action and romance, we don’t know who the bad guy is.

The whodunit, however, is really a MacGuffin. The movie is more concerned with investigating the changing mores and hypocrisies of the West and predicting the inherent dangers in the proliferation of weaponry. It’s worth remembering that the movie came out at time when mass murderers such as Charles Whitman (the subject of Peter Bogdanovich’s Targets, 1968) who went on a killing spree in 1966 were becoming the norm.

A card sharp is lynched for cheating at poker in the quiet town of Rinchon where late-night gambling is the height of entertainment. One of the players, professional gambler Van (Dean Martin), attempts to stop the hanging but is beaten up for his troubles. No surprise then, that he ambles off to Denver. Sometime later the hangmen begin dying off and Van returns not just to solve the mystery but to ensure that his name isn’t on the list. “If someone is out to kill you, you don’t sit around and let him pick the time,” he concludes. With the number of killings, not to mention brawls and shoot-outs, it’s almost continuous action.

On his return, Van discovers, with a gold strike nearby, the incipient boom town has attracted unsavory elements, not just the high murder quotient but a whorehouse and loud music in the saloon. Acting as counterbalance is gun-toting preacher Jonathan Rudd (Robert Mitchum) who announces his presence by spraying bullets in the saloon floor, emerging as the self-proclaimed “conscience” of the town.

For a sometime protector of law and order, Van is rather lax in the morals department, unwilling to commit to main squeeze rancher’s daughter Nora (Katharine Justice) when the likes of Lily (Inger Stevens), the unlikely proprietor of a barbershop-cum-whorehouse, are on hand. Van is an interesting study. Once he becomes aware that the only people likely to end up in an early grave are the six men who played poker with the lynched individual, it doesn’t occur to him to fess up to Marshal Dana (John Anderson) which would ease the fears of the ordinary public. Awareness the only corpses belonged to the guilty would have prevented further outbursts of violence among a disaffected population. Interestingly, too, Dana makes no attempt to investigate the lynching.

At the core of this picture are a couple of amazing scenes as paranoia takes hold. One miner, without the slightest sense of irony, complains that in the old days a gunfight took place face to face, not by a murderer slinking round in the dark. Rudd adds some prophetic advice: “wear a gun and use it fast, wear a gun and use it slow – I say don’t wear a gun and you won’t use it at all.”

Van likes to think he has the measure of women, when in fact they have the measure of him. The story avoids the obvious lure of a love triangle, of jealous women competing for Van’s affections. Both the young Nora and the more mature Lily are pretty well grounded. “One wore-out no-account kiss” is Nora’s dismissive description of Van’s attempts at romance while Lily lets Van know she has taken a shine to him as a matter of convenience, he’s just a man and she hasn’t had one in three years. Expecting to be treated as a pariah, Lily, expressing the notion that “women don’t usually like women who like men,” strikes up a friendship with Nora.

Marshal Dana finds it increasingly difficult to maintain any kind of peace since as the death count mounts, paranoia grows rife, exacerbated by the kind of greed gold fever brings, resulting in citizens determined to challenge authority and take matters into their own hands.

The most antsy character is Nick (Roddy McDowall), Nora’s brother and the leader of the lynch mob. Nick seems to stir up bad feelings, provoking the ire of both his father and Van. The guilty are despatched in original ways, one man “drowns” in a barrel of flour, another strangled by barbed wire, a third wakes the town at night when the church bell to which his neck is attached starts ringing out. It’s not too hard in the end to work out who the killer is, but as I said, that is not the point of the picture, although the ending is satisfactory.

There a mass of small detail of the kind that director Henry Hathaway (True Grit, 1969) tends to work into his pictures. Van is a cut above. He travels to Denver and back by stagecoach not on horseback. Citizens can purchase Pocahontas Remedies and beer from the Denver Brewery. Shaves and haircuts at the Tonsorial Parlor are reasonably priced but “miscellaneous” comes in at $20. After the preacher shoots up her floor, saloon owner Mama (Ruth Springford) smooths out the holes.

And there is some distinctive direction. Rudd’s sermon that lasts nearly 90 seconds is delivered in virtually one take, a fistfight is conducted in silence except for a soundtrack punctuated by grunts and punches hitting their target, a dying man tries to leave a physical clue about the identity of the mysterious killer. And there is a superb main street gunfight with Van trying to rescue the marshal and Rudd striding down the street in old-fashioned gunslinger mode.

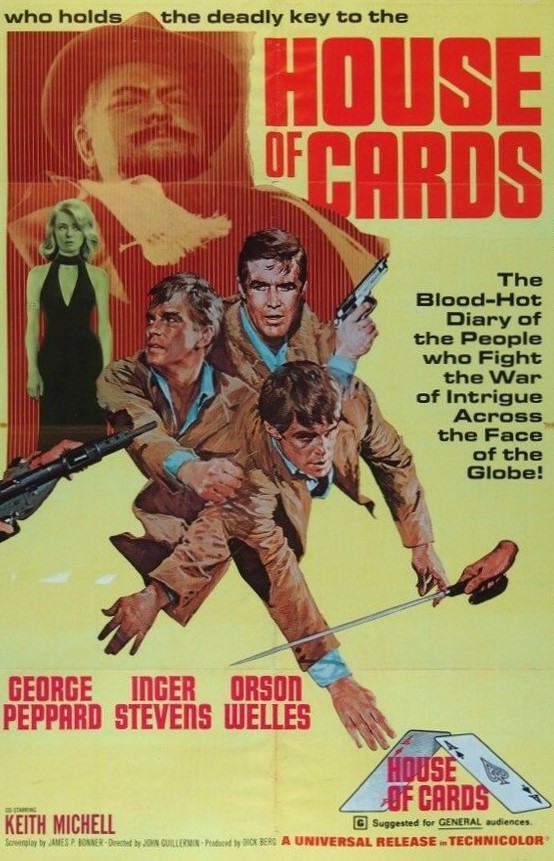

Dean Martin (Rough Night in Jericho, 1967) and Robert Mitchum (The Way West, 1969), both with apparently easy-going but magisterial screen personas, come off well together. Inger Stevens (Firecreek, 1968) always a great screen presence, an ethereal beauty, is vulnerable and strong at the same time. Katherine Justice (The Way West, 1967) is sassy and independent-minded and has a terrific facial response to coming across the first murder. John Anderson (The Satan Bug, 1965) leads a fine supporting cast including Yaphet Kotto (Live and Let Die, 1973), Denver Pyle (Shenandoah, 1965) and Whit Bissell (Seven Days in May, 1964).

Screenwriter Marguerite Roberts, adapting the novel by Ray Gaulden, contributes some classic lines. “If that is a Bible, read it,” Van instructs Rudd, assuming the preacher has a gun planted in the Holy Book, “If it ain’t a Bible, drop it.” There’s a nod to a James Coburn scene in The Magnificent Seven (1960). Congratulated on his marksmanship in hitting the spinning wheels of a windmill six times out of six, Rudd protests his shooting was a failure since he was aiming for the spaces in between. It was ironic that her next assignment concerned a lawman who took much the same no-holds-approach to the criminal fraternity (True Grit, 1969) as the killer in this picture.

I was so intrigued by this picture, realizing it had much more to offer than a whodunit, that I watched it again within a few days and was pleasantly surprised by its depths.