The making of this could have been a movie in itself. The novel, published in 1952, suffered from a long gestation involving four directors with seven actors at various points either signed up or mooted for the two top main roles.

Journalist-turned-author Paul Wellman specialized in westerns and historical non-fiction with a western bent. The Comancheros was the last of the half-dozen of his near-30 novels to reach the screen, following Cheyenne (1947) with Jane Wyman, The Walls of Jericho (1948) with Cornel Wilde and Linda Darnell, Alan Ladd as Jim Bowie in The Iron Mistress (1952), Burt Lancaster as Apache (1954) and Glenn Ford as Jubal (1956).

Originally earmarked by George Stevens as a follow-up to his Oscar-nominated Shane (1953), it was scheduled to roll before the cameras on completion of Giant (1956) in a Warner Bros production that contemplated re-teaming Vera Cruz (1954) pair Gary Cooker and Burt Lancaster. When that failed to gel, next up were Gary Cooper and James Garner. That was kind of a tricky proposition given that Garner had taken on the might of Warner Brothers in a lawsuit in a bid to extricate himself from his contract.

But the producer didn’t seem to care as the day the actor won the lawsuit he received the script. “I didn’t like it, I didn’t want to do it,” recalled Garner, “but a couple of days later I heard Gary Cooper was going to do it,” resulting in a speedy change of heart. However, despite his verbal acceptance, no contract appeared and never hearing from Fox again assumed foul play from Warner studio head Jack Warner.

Meanwhile, Stevens’ interest had cooled and after settling on The Diary of Anne Frank (1959) he sold the film rights off to Twentieth Century Fox for $300,000, more than he had originally paid the author. Fox hired Clair Huffaker (Hellfighters, 1968) to write the script with Cooper’s sidekick role assigned to the up-and-coming Robert Wagner (Banning, 1967). But Cooper’s ill-health prevented that version going ahead.

not appearing until three months after the movie opened.

Television director Douglas Heyes (Beau Geste, 1966) was set to make his feature film debut with the plum cast of John Wayne and Charlton Heston, fresh off global monster hit Ben-Hur (1959). Ironically, Wayne could have made this movie years before, in 1953 having been sent the novel by then-agent Charles Feldman (who had clearly also contacted Stevens).

Wayne had come back into the equation after signing a three-picture deal with Fox. But Heston, on reflection, decided it would not be in the interests of his career at this point to take second billing and dropped out.

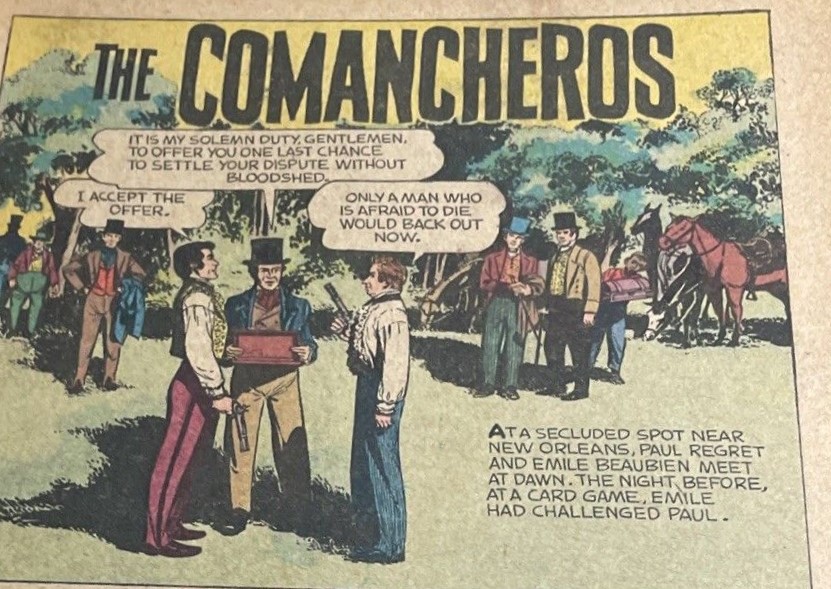

Wayne’s involvement meant re-shaping the script. In the novel the main character was Paul Regret, the Louisiana gambler wanted for murder for killing a man in a duel. Wayne was too old to play him so to puff up his part the Huffaker script was rewritten by James Edward Grant, better known originally as a short story writer, who had begun working for Wayne on The Angel and the Badman (1947) and would continue to do so for another 11 projects ending with Circus World (1964).

Another newcomer, Tom Tryon (The Cardinal, 1963), was lined up to play Regret. Then Heyes dropped out leaving the way clear for the final teaming of Hungarian director Michael Curtiz (Casablanca, 1942), now a freelance after decades with Warners, and John Wayne.

Stuart Whitman (Murder Inc, 1960) arrived from left field. While starring as Francis of Assisi (1961) he was shown the script by that film’s director, Curtiz. Tryon was eased out after Whitman managed to secure an interview with Wayne and the pair hit it off.

That Curtiz was already suffering from cancer was obvious to Whitman. Whatever sympathy his illness might have attracted was scuppered by the director’s rudeness. He had a predilection for sunbathing in the nude and blowing his nose on tablecloths, the actions of a powerful figure letting everyone know he could get away with it. His illness meant he restricted working to the mornings. After lunch he fell asleep in his chair, the crew placing umbrellas over his head to protect him from the sun.

While the director dozed, Wayne took over the directorial reins. When Curtiz was hospitalized, the actor finished the picture. It is estimated that he filmed over half of it, including the climactic battle.

Ina Balin, a Method actor, found her acting style cut little ice with Wayne. When she demanded rehearsals and long discussions about her character, he simply shot the rehearsal. “Cut. Print. See how easy this is,” explained the actor after wrapping her first scene with him using the rehearsal take.

“Duke was a terrific director,” observed Stuart Whitman, “as long as you did what he wanted you to do. Shooting with him was very easy although Ina Balin…pissed him off. Before each shot, she’d dig down and get emotional and he was a little impatient: get the goddam words out, he’d mutter to himself.”

Jack Elam, playing one of the heavies, had won in a poker game with their handler a pair of camera-trained vultures. The daily fee for the birds to sit on a branch was $100. Elam thought he’d get cute and ramp up the price to $250. That notion didn’t sit well with Wayne and he soon reverted to the original price.

While on the set, Curtiz fired third assistant Tom Mankiewicz, later a screenwriter, but currently just a lowly nepo, owing his job to the fact he was son of director Joseph L. Mankiewicz. Tom’s downfall was arguing with Curtiz over his plans for the stampede scene for which he had rented dozens of Wayne’s prized longhorns. Asking the cattle to go over a 5ft drop and scramble up the other side was a good way of breaking their legs. Having informed Wayne of the director’s proposal, he was told by the star to turn up for work the next day, by the time the actor had finished chewing out the director that would be the least of his problems.

Despite friction with Curtiz, Wayne was surrounded by old friends and colleagues, including producer George Sherman, cinematographer William Clothier and screenwriter James Edward Grant. “Duke and George Sherman grew up together working at Republic for $75 a week and all the horses you could ride,” explained Clothier. “They were old friends. Duke didn’t understand old Mike Curtiz very well and I must say he didn’t try very hard. Mike was just plain out-numbered and I felt sorry for him.”

Although set in Texas in 1843, parts of the film were shot in Utah and the cast used weapons such as the Winchester lever-action rifles and the Colt Peacemaker which were not in production for another three decades.

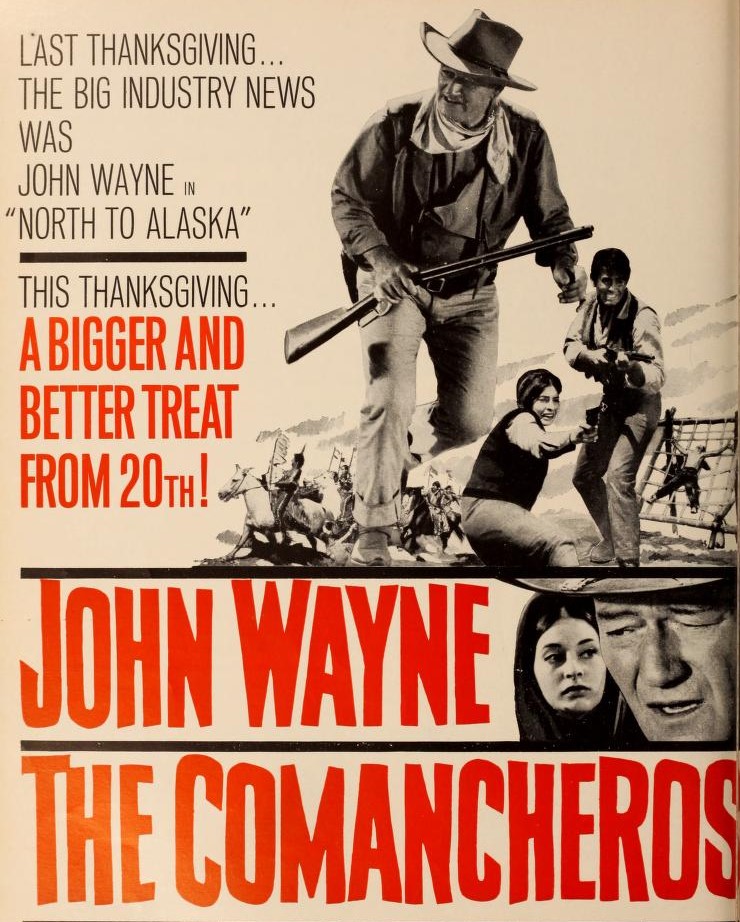

Michael Curtiz, after nearly half a century directing movies, died shortly after the film’s release. The Comancheros, a box office smash, helped balance Wayne’s finances after the financial hit of The Alamo and solidified the notion that as far as is career went he was better concentrating on westerns than anything else.

For some reason, U.S. box office figures are sketchy but it was a huge hit around the world, finishing seventh for the year at the British box office for example, and re-emphasizing the Duke’s resounding global popularity.

SOURCES: Scott Eyman, John Wayne, His Life and Legend, (Simon and Schuster paperback, 2014) p352-357; Howard Thompson, “Wagner Steps Up Work In Movies,” New York Times, January 21, 1961, p18; Lawrence Grobel, “James Garner, You Ought To Be in Pictures,” Movieline, May 1, 1994