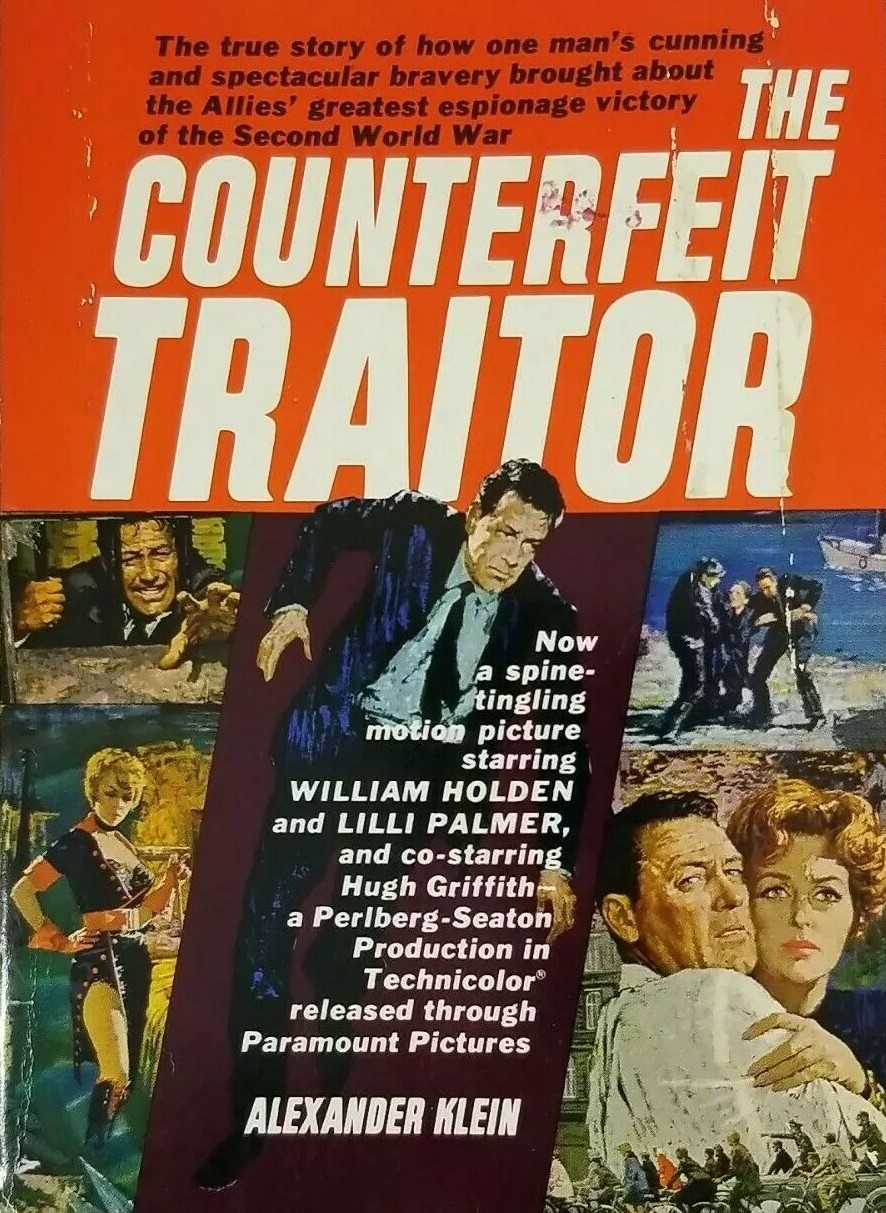

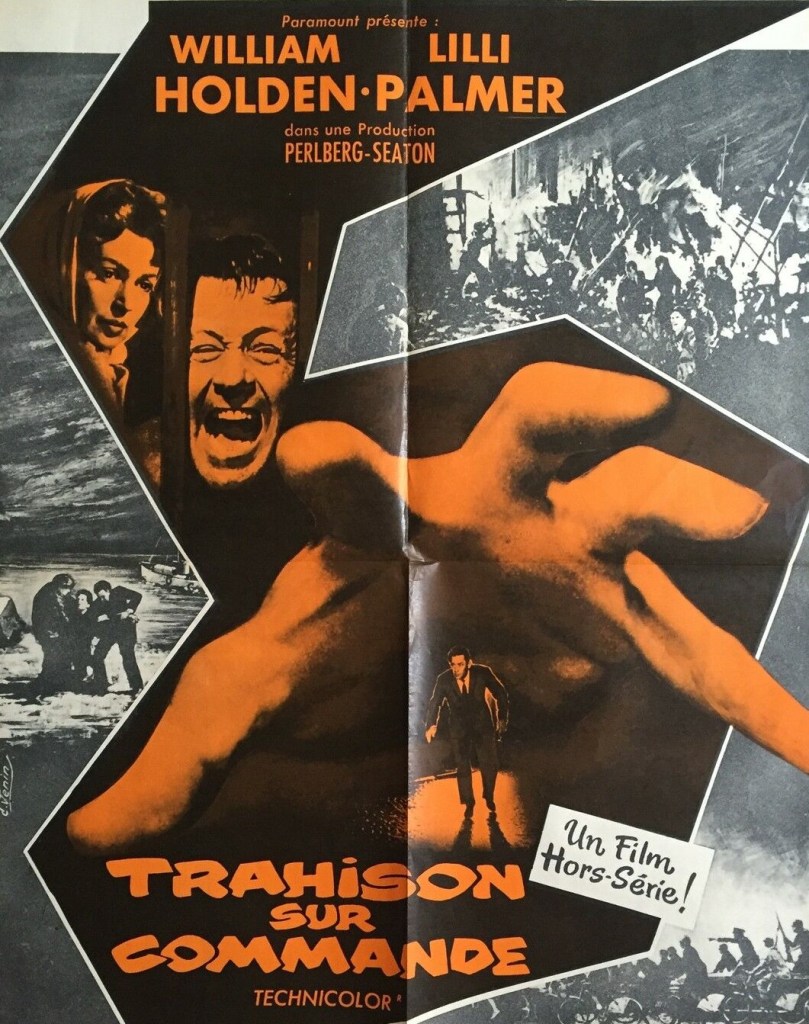

Cynical and opportunistic Swedish oil executive Eric Erickson (William Holden) blackmailed into World War Two espionage finds redemption after witnessing first-hand the horrors of Nazi Germany. Two extraordinary scenes lift this out of the mainstream biopic league, the first Erickson witnessing an execution, the second a betrayal. While some participants in the espionage game pay a terrible price, others like spy chief Collins (Hugh Griffiths) manage to maintain a champagne lifestyle.

Structurally, this is something of a curiosity. The first section, with over-emphasis on voice-over, concerns Holden’s recruitment and initial attempts at spying on German oil installations on the pretext of building a refinery in Sweden. Although resenting the manner in which he was recruited, Erickson had no qualms about resorting to blackmail himself to enlarge his espionage ring.

But it’s only when Marianne Mollendorf (Lili Palmer) enters the frame as his contact in Germany that the movie picks up dramatic heft. As cover for frequent meetings, they pretend to be lovers, that charade soon deepening into the real thing. While abhorring Hitler, she suffers a crisis of conscience after realizing that the information she is passing on to the Allies results in innocent deaths. The final segment involves Erickson’s thrilling escape back home.

The picture is at its best when contrasting the unscrupulous Erickson with the principled Marianne. Virtually every character is trying to hold on to way of life endangered by the war or created by the conflict and there are some interesting observations on the way Erickson manages to harness foreign dignitaries while being held to hostage in his home country. Loyalties are sparing and even families come under internal threat.

Sweden was neutral during the Second World War so in assisting the Allied cause Erickson was effectively betraying his country and once, in order to keep proposed German investors sweet, he begins to spout Nazi propaganda at home finds himself deserted by friends and, eventually, wife.

In some respects, William Holden (The Devil’s Brigade, 1968) plays one his typical flawed personalities, easy on the charm, fluid with convention, but once he learns the true cost of his espionage a much deeper character emerges. The actor’s insistence, for tax reasons, on working abroad – this was filmed on location in Europe – would hamper his box office credibility and although not all his movie choices proved sound this was a welcome diversion. Whether American audiences were that interested in what a Swede did in the war was a moot point, as poor box office testified. And the title might have proved too sophisticated for some audiences, given there was no counterfeiting of money involved.

Lili Palmer (Sebastian, 1968) is excellent as the manipulative Marianne, betraying her country in order to save it from the depredations of Hitler, not above using her body to win favor, but paralyzed by consequence. Hugh Griffith (Exodus, 1960) provides another larger-than-life portrayal, disguising his venal core.

Werner Peters (Istanbul Express, 1968) puts in an appearance and Klaus Kinski (Five Golden Dragons, 1967) has a bit part.

Double Oscar-winner George Seaton (Airport, 1970) makes a bold attempt to embrace a wider coverage of the war than the film requires and could have done with concentrating more on the central Erickson-Mollendorf drama, especially the German woman’s dilemma, but it remains an interesting examination of duplicity in wartime. Written by the director based on the novel by Alexander Klein.