The rocking chair motif in this underrated film is ignored while the door opening and closing in The Searchers (1956) is hailed as one of cinema’s greatest images. Welcome to the world of director Henry Hathaway (Nevada Smith, 1966). Way down the pecking order when it comes to the makers of great westerns, below Sergio Leone (Once Upon a Time in the West, 1969) who only made four and Howard Hawks (Rio Bravo, 1959) only three.

Closer inspection, too, of The Wild Bunch (1969) might reveal cinematic ideas that turned up here first. Closer inspection of John Wayne (The Commancheros, 1961) might reveal a mighty fine, very touching, performance.

The genre was chock-full of vengeance, but here that is tempered by mystery over the death of their father, a drunken gambler, that has led to the loss of the family ranch, leaving the mother, for whose funeral the titular sons return, living hand-to-mouth, supplementing the usual sewing and mending with giving guitar lessons.

Hastings (James Gregory), a businessman with big ideas, has taken over the ranch and pretty much the local town of Clearwater. And he’s just hired extra muscle, notorious gunslinger Curley (George Kennedy), to swell his already-growing army.

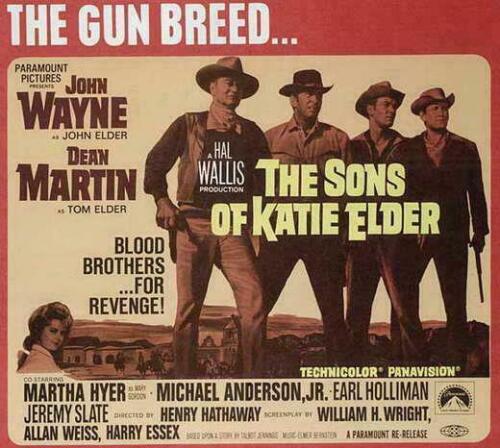

Only the youngest son, Bud (Michael Anderson Jr), a reluctant college student, is clear of the taint of wrong-doing. John Elder (John Wayne) has a reputation as a gunfighter but unlike shifty younger brother Tom (Dean Martin) doesn’t have a wanted poster following him around. The other son Matt (Earl Holliman) takes after John, some shady action but no legal consequence.

This is certainly not a great fraternal union. When they’re not engaged in low-level investigation or trying to prevent themselves being lynched, they’re bickering and fighting. The only thing that unites them, beyond love of the deceased woman, is determination to continue paying for Bud’s education.

Apart from the ranch, one of Hastings’ other lucrative investments is a firearms business, which allows him to tote around a telescopic rifle which, of course, ensures he can bump off those who get in his way from a distance, without fear of discovery. The easiest way to get rid of the brothers is to have them arrested for murder and to kill off the one man, Sheriff Wilson (Paul Fix), who might have the brains and experience to work out something fishy was going on.

John Wayne is more emotional here than in any picture since The Searchers, though, as you’ll be aware, his emotion is registered through his eyes or bits of business rather than a lengthy speech. And given double duty of looking after the youngest while holding back the more tempestuous Tom.

Dean Martin’s (Five Card Stud, 1968) charm runs thin, as is intended, no woman to gull, and no cliché alcoholism a la Rio Bravo to fall back on. It’s a part he plays completely against type, although you can sense he’s bursting out of those confines in the false eye con. He’s pretty much always brought to heel by Wayne. The one time he defies big brother ends in personal calamity. Imagine a marquee name as big as Dean Martin taking on a role where the part sets him up to be walking in the Duke’s shadow, despite his efforts to break loose.

In fact, unusually for a western, until Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969) came long, it’s replete with reversals. Hathaway plays with expectations from the outset, the opening sequence of big beast of a train puffing through fabulous scenery doesn’t bring John, instead, unknown to the waiting brothers, Curley disembarks. Katie Elder’s friend Mary (Martha Hayer) cuts off at the pass any idea the audience might have of incipient romance when she gives John both barrels.

Thanks to the screenplay, Michael Anderson Jr.(Major Dundee, 1965) and Earl Holliman (The Power, 1968) are given more bite than their roles might suggest and James Gregory (The Manchurian Candidate, 1962) makes his villain meaty though you suspect the presence of George Kennedy (Cool Hand Luke, 1967) is another lure, creating audience expectation that is not fulfilled. Martha Hyer (The Chase, 1966) is more conscience than glamor, spending most of the time on the sidelines.

You’d be surprised just how lean a production this is, and equally how deftly Hathaway avoids cliches. Just because there’s a kid you don’t need to teach him how to be a man. A huge herd of horses doesn’t need to stampede. Beautiful woman in the vicinity doesn’t necessarily call for a heated love affair. Ending up in jail doesn’t necessitate a bust-out. Villainous gunslinger doesn’t set up obligatory shootout in an empty street.

Hathaway’s unusual, too, in the way he anchors his pictures in reality. Here it’s a funeral director washing the wheels of his hearse, a blacksmith applying shackles.

You’d marvel, too, at just who was involved in fashioning the terrific screenplay: veteran William H. Wright, his first in two decades, Harry Essex (Creature from the Black Lagoon, 1954) in his first in eight years, and Allan Weiss whose six other movies were all Elvis Presley vehicles. Hardly the pedigree to produce one of the best westerns of the decade. This is the kind of screenplay where no line is wasted, not when a retort can be used to define character.

Most people remember the rousing theme by Elmer Bernstein (The Scalphunters, 1968), but actually there are also some very innovative musical passages worth listening out for.

Curiously, it was Andrew Sarris, hardly a John Wayne fan, who recognized the movie’s attributes, though in niggardly fashion, “The spectacle of people in Hollywood trying to do something different in a western at this late date is reassuring.”

It’s about time those differences and the picture’s excellence were recognized.