Cinerama was the IMAX of the day and far superior in my view in many aspects not least the width of the screen. IMAX goes for height but I’m not convinced that compensates for lack of the widest screen you could imagine. So the chance of seeing this in the original Cinerama print, 70mm and six-track stereo, at the annual Bradford Widescreen Festival yesterday was too good to miss. And so it proved. A thundering experience. Much as I enjoyed it on DVD, this was elevated way beyond expectation.

Superb even-handed depiction of war, far better than I remembered. Most war films of this era and even beyond showed the action primarily from the view of the Americans/British – even the acclaimed The Deer Hunter (1978) and Apocalypse Now (1979) show nothing of the skills of the Vietnam forces that would prove victorious. And while The Longest Day (1962) shows reaction to the invasion, the Germans are revealed as caught on the hop. Given the basis for this picture is the unexpected German offensive in the Ardennes, France, in December-January 1944-1945, you might expect the Germans to be accorded some attention. But hardly, given as much of the picture as this, so that in the early stages the Germans are portrayed as powerful, clever and patriotic while the Americans are slovenly and complacent, their greatest efforts expended on preparing for Xmas.

With tanks the main military focus, Cinerama is deployed brilliantly, the ultra-wide screen especially useful as the unstoppable vehicles rampage through forests and land and allowing true audience involvement when opposing armies meet head-to-head. Of course, it being Cinerama, there are a couple of scenes that play to the strength of this particular screen, a car careening round bends and a train racing along twisting tracks, the kind of scenes that previously would have had the audiences out of their seats with excitement, but here mainly used to raise the tension in the battle.

It’s to the film’s benefit that the all-star cast doesn’t feature a single actor who is truly a star in the John Wayne/Gregory Peck/Steve McQueen mould so that prevents the audience rubbernecking to spot-a-star that afflicted The Longest Day. The biggest name, technically, is Henry Fonda, and although he received top billing in many pictures, you would have to go back to The Wrong Man (1956) to find an actual box office hit. The only previous top billing for Robert Shaw (From Russia with Love, 1963) had been in The Luck of Ginger Coffey (1964), a flop few had seen. And the top-billing days of Robert Ryan (Horizons West, 1952) and Dana Andrews (Laura, 1944). In fact, the actor with the biggest string of hits was Disney protégé James MacArthur (Swiss Family Robinson, 1960). Anybody who had seen The Magnificent Seven (1960) and The Great Escape (1963) would recognise Charles Bronson in a supporting role. So fair is the movie that it’s the blond-haired Shaw who steals the show with a dynamic performance.

So it helped the almost documentary-style of the film that it was filled with familiar faces rather than dominant stars and the director was not bound to give a star more screen time or provide them with one brilliant scene after another, or establish a redundant love story in order to provide them with more emotional heft. In fact, the only romance goes to a sly black marketeer who views his relationship more as a business asset.

Initially, the role of Lt. Col. Kiley (Henry Fonda), a former cop, seems only to be to rile his superiors General Grey (Robert Ryan) and Colonel Pritchard (Dana Andrews), his pessimistic view contrasting with the accepted notion that the Germans are well and truly defeated and the war would be over soon. On airplane reconnaissance he takes a photograph of an officer later identified as Panzer tank genius Colonel Hessler (Robert Shaw). While Grey and Pritchard over-ride his conclusions, the movie concentrates on the German build-up, their discipline, efficiency, leadership and determination juxtaposed to the American inefficiency and sloppiness.

Where the Americans just want to get home, Hessler – more charismatic than any of the dull Yanks – is in his element, wanting the war to never end, convinced at least that a tank-driven assault would drive a wedge between the Allied forces, and reaching the target Antwerp in Belgium in the north would extend the war by another year by which time Germany’s V2 rockets would give them greater firepower. The Germans also have a clever idea, the type that the British were always coming up with and would make a film of its own, of parachuting American-born Germans behind enemy lines, dressed in American uniforms to carry out vital sabotage and hold crucial bridges across the River Meuse.

In one of the best scenes in the film, his tank commanders spurt spontaneously into a patriotic song with much stamping of boots. And while Hessler’s immediate superior (Werner Peters) , ensconced in a superior bunker, can enjoy a comfortable lifestyle, no more illustrated by the fact that he has courtesans to hand, one of whom, offered to Hessler, is furiously dismissed. And the clock is ticking, the Germans have limited supplies of fuel and must reach the enemy’s supply dumps before they run out of gas.

The maverick Kiley manages to be everywhere – the River Meuse bridge, in the air in the fog determinedly hunting for the panzers he believes are hidden, is the one who realises how critical the fuel situation is for the enemy, and at the fuel depot for the movie climax. Otherwise, the picture uses its cast of supporting characters to cover other incidents, the massacre of prisoners of war at Malmedy, the chaos as the Germans over-run American-held towns.

Best of all is the human element. It would be easy on a picture of this scope to lose emotional connection, as you would say was the prime flaw of The Longest Day. Not only is Kiley the outsider trying to beat the system, but we have the cowardly Lt Weaver (James MacArthur) who would rather give up without a fight than lose his life, the weaselly Sgt. Guffy (Telly Savalas) representing the worst instincts of the grunts, the confused General Grey can’t make up his mind how to respond to the sudden attack, and Hessler’s driver Conrad (Hans Christian Blech) who is fed up with paying the price of war.

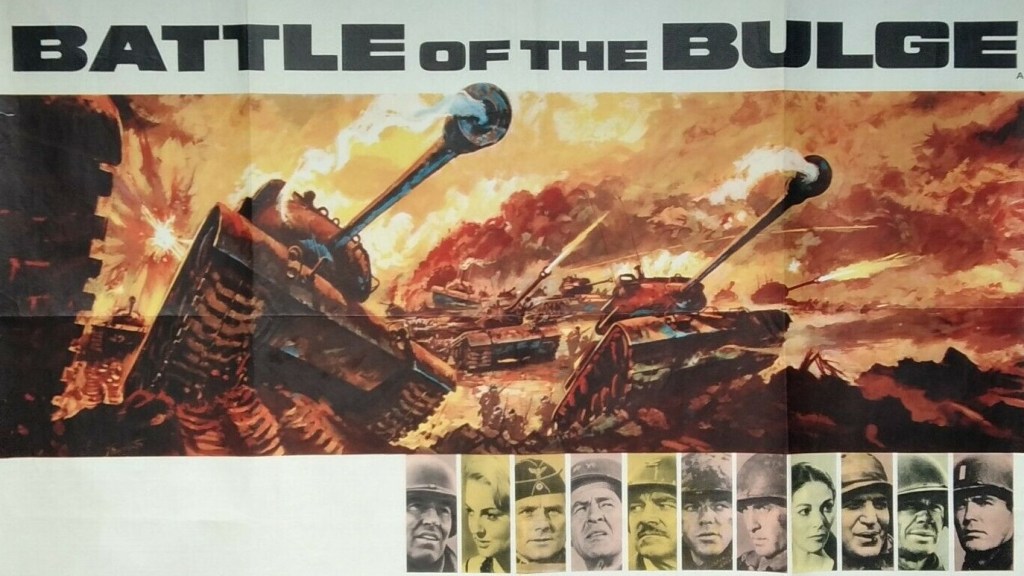

The action scenes are outstanding. If you’ve never been up against a tank in full flight, you will soon get the idea how fearsome these metal battering rams are, as the rear up, crash over trees, race across open fields, and either with machine gun or shells wreak havoc. As with the best war films, you are given very precise insights into the battles, the tactics involved, the ultimate cost. Wolenski (Charles Bronson) is in the thick of the fighting.

While Robert Shaw is easily the biggest screen personality, Henry Fonda is solid, and holds the various strands of the picture together, while Charles Bronson enjoys a further scene-stealing role. But the pick of the acting, mostly thanks to bits of improvisation, is Telly Savalas (The Slender Thread, 1965) as the thieving Guffy. In one memorable scene he kicks out in resentment at his collection of hens and in another shakes his body at the tanks. No one else, beyond Shaw, comes close to his infusing his character with elements of individual personality.

Pier Angeli (Sodom and Gomorrah, 1962) as Guffy’s mistress and Barbara Werle (Krakatoa, East of Java, 1968) as the courtesan are inexplicably billed above Charles Bronson, Telly Savalas and James MacArthur perhaps in a ploy to deceive audiences into thinking there was more female involvement.

Full marks to British director Ken Annakin (The Biggest Bundle of Them All, 1968) for visual acumen and for simplifying a complicated story and peppering it with human detail. His battles scenes are among the best ever filmed. Credit for whittling down the story into a manageable chunk goes to Philip Yordan (The Fall of the Roman Empire, 1964), Milton Sperling (The Bramble Bush, 1960) and John Melson (Four Nights of the Full Moon, 1963).

A genuine classic, with greater depth than I ever remembered.