When we talk about realistic war movies, we generally mean ones chock-full of brutality and violence. But there was another reality rarely touched upon, and that was guys to trying to get through the whole shooting match without getting killed. Not cowards, necessarily, but people unwilling to take stupid action in the guise of blind obedience.

This ends up being a highly unusual and hence highly original take on the war picture. Where, in another film, enemies might duel fiercely to the death, attempting to outwit each other at every turn, this delivers on a more emotional, thoughtful, and human, level.

You wouldn’t have thought, either, that the combination of two wildly different humor codes, the more overt Italian and the laid-back British, would work. So in subject matter and style, this takes a helluva risk. Much of the effect rides on exposing as misleading the standard tropes regarding the different countries – that the Italians are weak and that Brits, feelings numbed by stiff upper lip and upbringing, never complain.

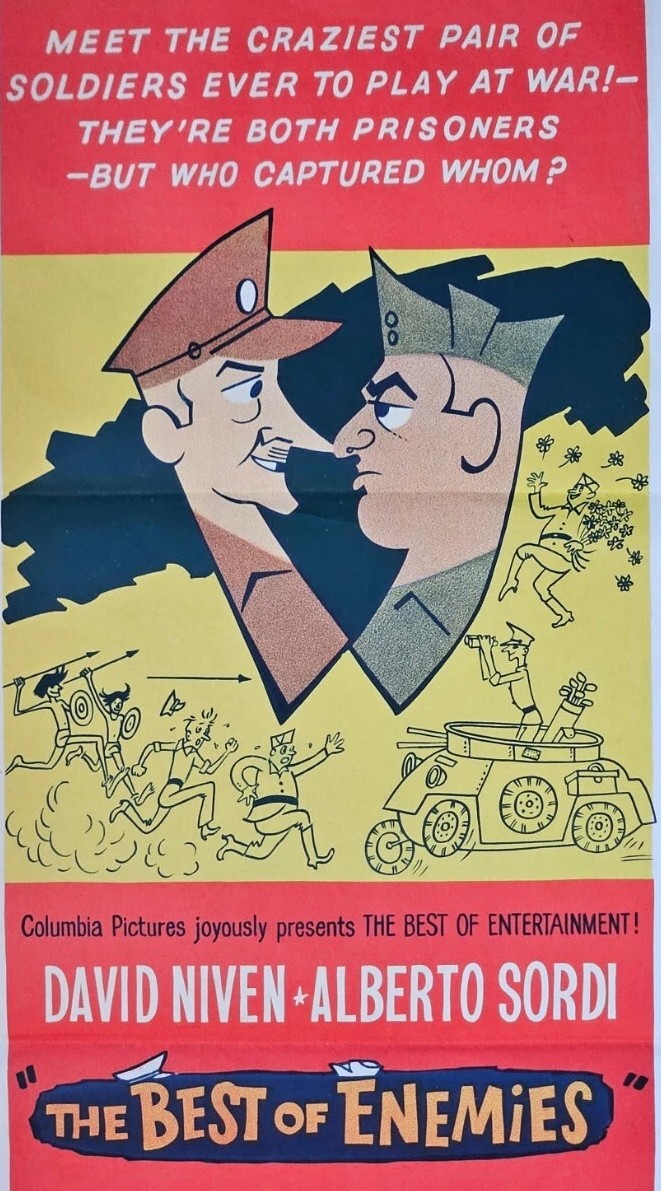

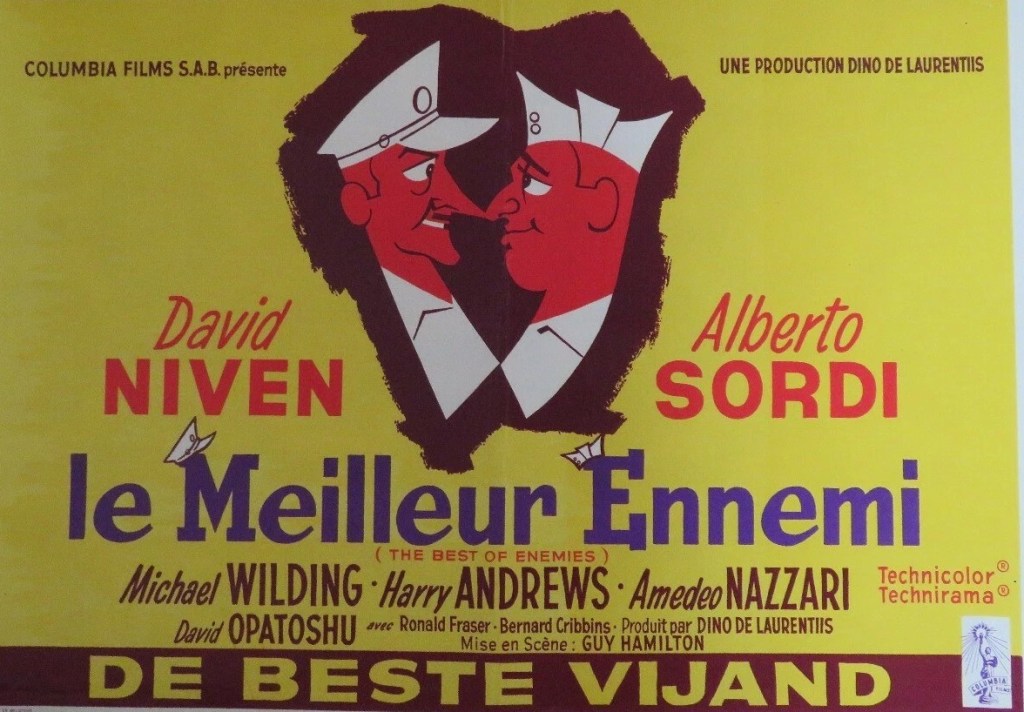

Major Richardson (David Niven), reconnaissance plane shot down in Italian-held Abyssinia (Ethiopia) in 1941 in World War Two, is captured in the desert by a unit led by Captain Blasio (Alberto Sordi). Blasio doesn’t want the responsibility of prisoners and encourages Richardson to escape, hoping that the Brit, taking note of how weak the Italian unit was, would leave them alone.

The opposite is true. The Brits would like nothing better than to capture a weak section of the Italian Army. So Richardson, leading a stronger unit with tanks and stuff, confronts the Italian who is furious that the man he let go has somehow reneged on an unwritten code of honor and come back. Using a simple ruse, the Italians escape.

The Brits nearly catch up with them several times but incompetence gets in the way. Then Blasio gets annoyed with some of his natives and cuts them loose and in revenge they start a fire that drives both Brits and Italians together. Blasio is happy to surrender since that means the Brits, devoid of transport after the fire, have to holster Italian rifles and carry on a stretcher any Italian, such as Blasio himself, who falls ill.

The enemies unite to escape an interfering native tribe but then Blasio gets the hump at Richardson once again, returning the Italians to prisoner status once they are free. Hiding out in an abandoned village, the Italians are put to work building latrines – and according to the British class system different ones for officers and soldiers. A bid by Blasio to put Richardson in his place misfires. The two units bond again over a game of football and when the tribesmen return Richardson breaks the rules by handing back the Italians their rifles. Only thanks to British incompetence there’s no Italian ammo.

So then, weapon-less, and nobody apt to take sides, they stagger over the desert, directed by Richardson to safety. Richardson and Blasio bond over wives and family. But when they reach a proper road, Richardson reverts to the status quo and insists the prisoners form up at the rear. Except, he’s got it all wrong and they have ended up in the Italian-controlled zone. Blasio can’t contain his delight, mocking the Brits, but not taking them prisoner. Except he’s got it wrong, too, as the desert campaign is over and the Brits are victorious.

It doesn’t end well for either officer. Richardson is threatened with being put in the catering corps, Blasio a bedraggled prisoner. But it finishes on an uplifting moment, Richardson instructs his men to present arms to the prisoners, indicating their mutual respect.

So, as I said, nothing like your usual war movie. Both commanders are incompetent. Richardson despises Blasio for not “putting any effort” into his job. Blasio can’t understand why Richardson takes the job so seriously. Even if it marked him down as a coward, Blasio’s wife just wants him home safe. Incompetence rules, mistakes are legion, and pettiness guides the action of the officers. Movie makers of the period tended to concentrate on the heroism of war, but there must have been a ton of expeditions like this that went awry.

The script allows both David Niven (Bedtime Story, 1964) and Alberto Sordi (Anzio, 1968) considerable latitude, the Englishman afforded a wider range than usual, the Italian encouraged to tone down the over-acting, so each turns in a more measured performance. Sordi was nominated for a Golden Globe and the movie was nominated for two other Globes including Best Foreign Film.

The supporting cast includes Michael Wilding (The Sweet Ride, 1968), Harry Andrews (The Hill, 1965) and David Opatoshu (Guns of Darkness, 1962).

Directed by Guy Hamilton (Battle of Britain, 1969) from a screenplay by Jack Pulman (The Executioner, 1970).

More rewarding and emotionally satisfying than I expected.