Role play wasn’t the sub-culture it is now. Though fashion had injected more of a sense of dressing up what with Russian furs courtesy of Doctor Zhivago (1965) and snazzy berets from Bonnie and Clyde (1967), the idea of people living out their lives in costume had not taken hold. So consider this a precursor – and maybe a warning – as to what can go wrong if taken too far.

Obscurity to the point of obfuscation was an arthouse default especially prevalent in more commercial ventures like Blow-Up (1966) and In Search of Gregory (1969) so no need to bother yourself with hunting out motivation or background.

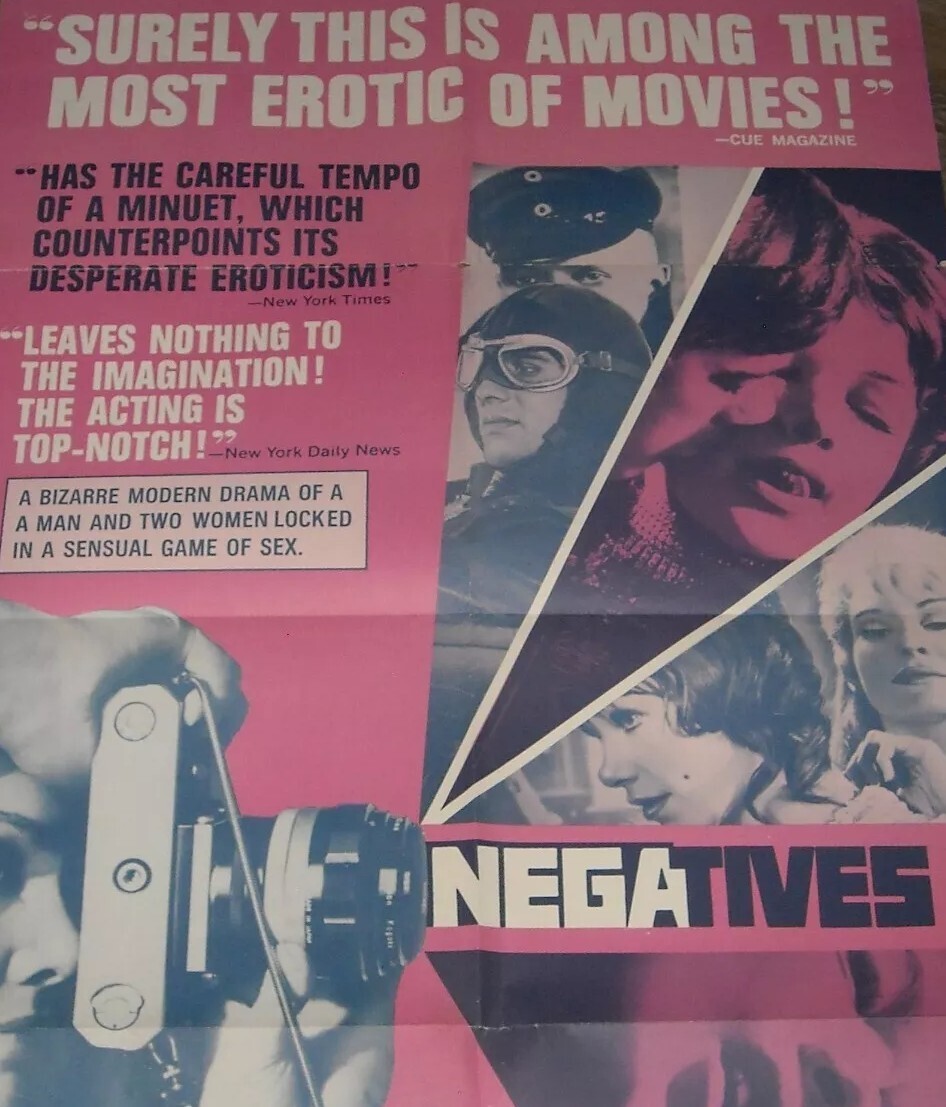

The erotic subtext – voyeurism too – here takes on a disturbing quality as it touches on the notion of male justified in using violence in response to female provocation. Drama centers on a clash of role model sensibilities with a weak male shifting from interpreting a murderous villain to imitating a heroic pilot.

Antiques dealer Theo (Peter McEnery) spices up his stale marriage to Vivien (Glenda Jackson) by dressing up as serial killer Dr Crippen. She invests in the role of his complaisant lover Ethel. Play-acting, at her behest it appears, doesn’t prevent her verbally tearing into him. Into this unconventional nest arrives German photographer Reingard (Diane Cilento) who has been spying on him for several weeks. She has her own fantasy and soon has him rigged out as World War One flying ace Baron von Richtofen, complete with ancient biplane. He responds to the militaristic characteristics of the pilot, entering more into the spirit of the game than the famed killer.

Naturally, Vivien doesn’t take kindly to this intrusion, not least because she realizes she isn’t the only one who can manipulate her malleable husband and violence and tragedy ensue. It’s not entirely clear why either female character indulges in such fantasies and does give rise to the cliche notion, and redolent of the times, of the female wishing to give in to the dominant male, even when the man shows little sign of being a dominant personality.

Apart from Theo visiting his father (Maurice Denham) who appears to be dying in hospital, the picture doesn’t shift much from its three-cornered narrative. The idea of the ongoing masquerade is emphasized by a sequence set in Madame Tussaud’s. Given the censorship of the times, the eroticism is largely of the discreet variety, rather than going down the full-blown sexual fantasy of The Girl on a Motorcycle (1969).

Glenda Jackson both plays a character right up her street and brings far more to the role than either Peter McEnery (The Moonspinners, 1964) or Diane Cilento (The Third Secret, 1964) who give the appearance of slumming it in a low-budget production in the hope it might bring career kudos.

Unwilling to dig any deeper into the characters, director Peter Medak (The Ruling Class, 1972), in his debut, merely toys with technique, elaborate shots following a character round a room or unusual compositions.

With the trendy crowd parading down King’s Road with all the latest hip gear including military uniforms and Victorian garb, this might have seemed to fit right in, except that the main characters have little in common with the “Youthquake” of the era.

On the one hand a true oddity with McEnery and Cilento well out of their comfort zones, on the other proof of what Jackson and Medak had to offer.

Might appeal to the role-playing crowd, more likely to those interested in early Glenda Jackson.