William Castle (The Tingler, 1959) was always a cult director but 60 years later this hits a contemporary bullseye with uncanny accuracy. It couldn’t be more Hitchcockian, down to the director making an appearance at the start and adopting the same lugubrious tones as Alfred Hitchcock did for his television series.

Bookended by two brilliant scenes, one of mystery, the other revelation, it’s only when you go back and unravel the way this has been put together you realise how fiendishly clever – and heartrendingly awful – it had been. Gender identity, in case you hadn’t guessed, is a central theme.

Castle wasn’t known for concentrating on any emotion beyond fear but this goes back to the most basic of all emotions. Who am I? How do I figure myself out? And even the acting – almost as black-and-white as the picture with one over-the-top character and one so weak he almost drains the picture of any life – makes more sense in retrospect.

Stunning blonde Miriam Webster (Jean Arless) checks into a hotel and offers bellhop Jim (Richard Rust) $2,000 to marry her that night on the understanding the marriage will immediately be annulled. Puzzled, and of course fancying his chances of sex as a tip, he drives her to local Justice of the Peace Alfred S. Adrims (James Westerfield) who demands an increased fee for getting dragged out of bed. In short order, Miriam murders him and his wife and escapes.

Turns out she’s not Miriam Webster. That’s the name of a florist in the town where Emily, her real name, looks after mute invalid Helga (Eugenie Leontovich). The real Miriam (Patricia Breslin) is half-sister to businessman Warren (George Marshall), returning home after a lengthy absence to claim his inheritance. At the age of 21, in a couple of days’ time, he falls heir to a $10 million fortune. Helga was his Danish nanny whom he resolved to provide care for after a heart attack.

But it’s soon clear that Emily hates her charge who can only communicate, and only to draw attention, by using a clacker to batter against her wheelchair. When Miriam visits Helga, Emily skips out, promising to return shortly, only to tell Miriam’s boyfriend Karl (Glenn Corbett) that she’s been detained and won’t be free to join him for a picnic.

Then she proceeds to smash up Miriam’s flower shop, in particular destroying anything that points to a wedding, and tearing up a photograph of Miriam’s half-brother. When Carl pops in, she knocks him out.

So what’s with all the wedding malarkey? You won’t be surprised to learn it’s something of a red herring, especially as Emily is already married to Warren, news that comes as a shock to Miriam.

Warren has the constitution of a weakling and looks the kind of boy who would have been trampled over as a child. Except, it turns out, he was bullied by his father, a driven businessman, and whipped by Helga to turn him into someone a lot sturdier, able to stand on his own two feet, and not get knocked around. If anything, he was inclined to be the bully.

Emily should have murdered the bellboy when she had the chance because of course he goes and rats on her and now there’s an illustration of her in the newspaper and the cops are on her trail having tracked down a Miriam Webster living in her town.

Naturally, Warren rejects the notion, but Miriam isn’t so sure. There was an incident in her bedroom and she had lied to Miriam about nipping out for a few minutes and something had been dropped among the debris in the florist shop that linked its destruction to Emily.

So if Emily’s married to a man who’s about to become a multi-millionaire and by far the richest guy in town and with who knows what influence that could buy…You see where this is going? Or if the deeply-in-love Warren could tolerate a wife with homicidal tendencies? Or if she would inherit should Warren have a nasty accident? You see where else this could be heading?

Well, it goes to none of those places. And I’m not going to spoil the climax by telling you exactly where it goes, but it’s a shocker for sure and just superbly done.

And once that revelation’s out in the open everything else makes sense – and doesn’t. For what is at its heart is something so jarring real and troubling, an emotion with consequence, that it neatly fits into one of the most compelling controversies of today.

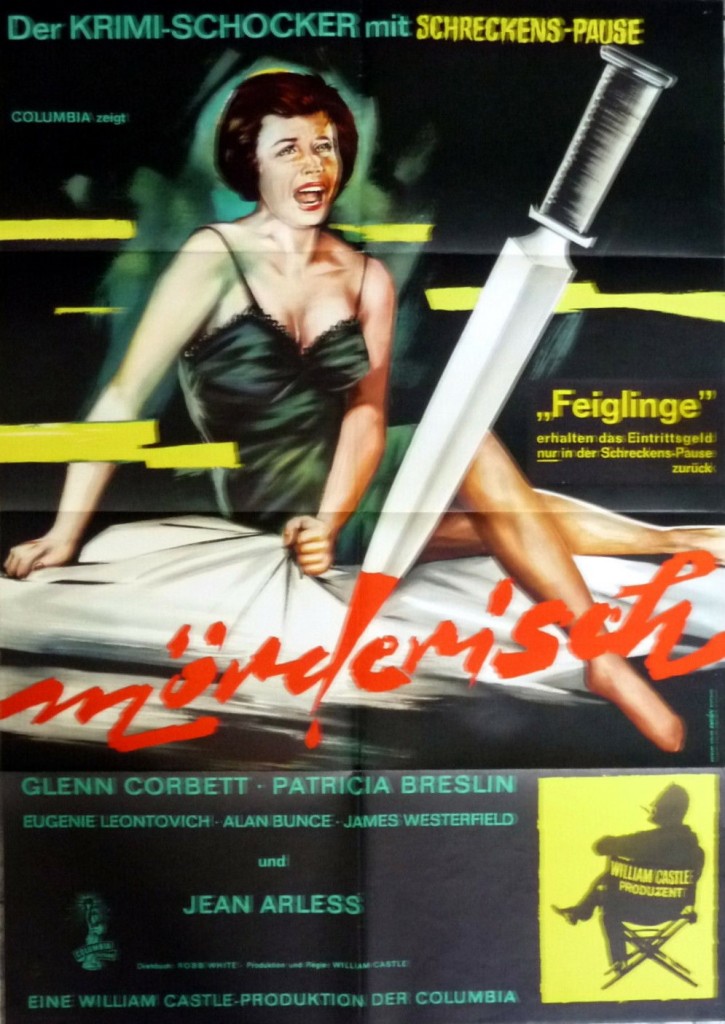

Otherwise, it’s a perfectly good straight-up thriller, owing much to Psycho (1960), especially the knife-wielding killer, but with some thrilling moments and, in another contemporary salute, busting open the fourth wall with the “Fright Break” gimmick where at the height of proceedings the director literally stops the clock and gives the audience 45 seconds to get out of the theater if they can’t take any more.

If you think William Castle has managed some sleight-of-hand I’m going to have to fess up and say I’ve done the same but you’ll only understand what if you watch the film. Anyone who guesses it can let me know.

There’s a prize. A copy of my latest book, shipped to anywhere in the world, 1960s Movies Redux, Volume 1 – printed copy available now, e-book shortly.