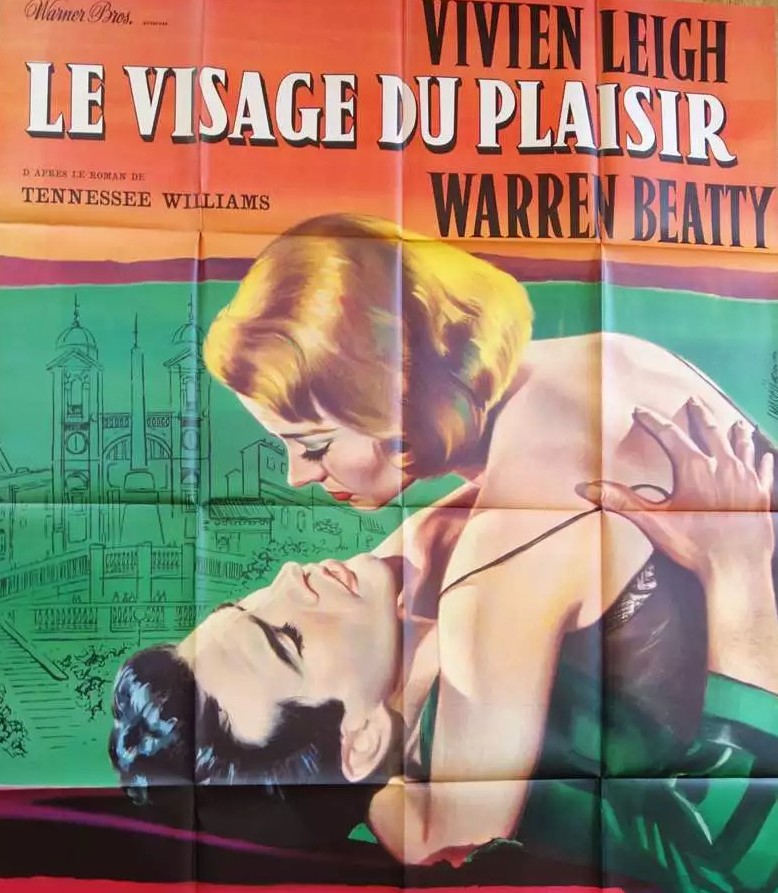

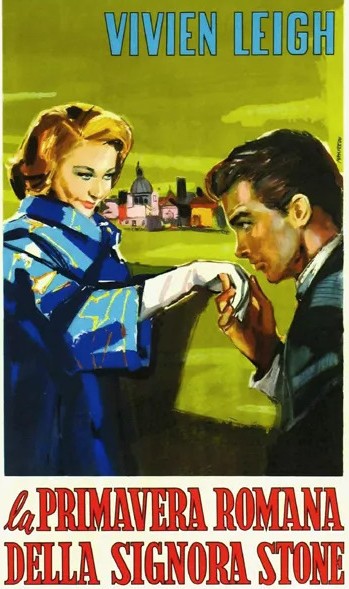

Dreary miscalculation. Ever since Tennessee Williams hit a home run with Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (1958), studios, directors and stars had clamored for his works, so much so that Hollywood had greenlit seven adaptations in five years. While box office was one consideration, the playwright was catnip to the Oscar, racking up 17 nominations with a hefty number in the Best Actress category.

However you dressed it up, his work contained a substantial number of portraits of sadness and malevolence and often teetered on the murky, so making them work at all depended not just on the acting and direction, but the initial story. Rather than being based on a play, this was sourced from his first novel, a bestseller.

But the tale never shifts out of first gear and it’s difficult to summon up sympathy never mind interest in any of the characters. The middle-aged romance had proved a cumbersome fix for studios, and since May-December numbers featuring ageing male and younger female had proved popular, Cary Grant set up with an endless supply of woman nearly half his age, it seemed only fair to give middle-aged actresses the opportunity to romance younger men.

Usually, however, this followed a more straightforward path, involving genuine feelings on both sides. But Hollywood was also digging into another cesspit, the female sex worker, somewhat dressed up in Butterfield 8 (1960) and Go Naked in the World (1961), treated more straightforwardly in Never on Sunday (1960) and Girl of the Night. So it only seemed fair to introduce the gigolo.

Stage actress Karen Stone (Vivien Leigh) heads for Rome with her wealthy husband to recover from the failure of her latest play, a Shakespearian outing. When her husband dies on the plane, Karen decides to hang on in the Italian capital, which, after a year, brings her into the orbit of gigolo Paulo (Warren Beatty) and his unscrupulous mentor/manager Contessa Magda (Lotte Lenya). While Karen isn’t entirely a dupe and quickly sees through Paulo, nonetheless a year of loneliness has taken its toll.

Plus she understands the attraction of the older lover, her husband being a good two decades older and willing to subsidize her theatrical and cinematic ambitions. Despite not falling for Paulo’s more obvious con tricks, Karen finds herself enmeshed in a one-sided romance, ignoring the warnings of friend Meg (Coral Brown) on the dangers of becoming the talk of the town with her lover clearly more attracted to rising movie star Barbara (Jill St John). Paulo quickly dumps the Contessa, leaving her free to pour bile into Karen’s ear.

Inevitably, the younger lover tires of the older, but generally such pairings work well enough because initially at least there is attraction on both sides. But when it’s as lop-sided as this no amount of long drawn-out close-ups of the disenchanted provide sufficient compensation for a story that overstays its welcome.

While there are hints of the decadence of La Dolce Vita (1960) that Fellini explored, here it’s more of a surface examination until the surprising ending, where you would think Karen is doing little more than willingly opening the door to a potential serial killer.

The only redeeming element, which might reverberate more easily today, is of the woman demonstrating her independence by being the one to choose, and to some extent discard, the man. While not for most of the movie a sexual predator, she may well have turned into one at the end.

Oscar-winner Vivien Leigh, in her first movie in six years, essays her role well but is compromised by portraying a character that fails to elicit sympathy. Warren Beatty (Promise Her Anything, 1966) avoids the trap of thickening his Italian accent and going wild with the gestures which lends his character more of a thoughtful personality but there’s not much here to write home about. Lotte Lenya (From Russia with Love, 1963) steals the show and was rewarded with an Oscar nomination. Jill St John (Tender Is the Night, 1962) plays the ingénue like an ingénue.

Unless you’re a student of theater I doubt if you’ll have come across Panamian director Jose Quintero. This was his only movie and he was more famous for staging some of Williams’ plays and for resurrecting Eugene O’Neill on Broadway. His inexperience shows in lingering on faces at the expense of creating drama. Gavin Lambert (Inside Daisy Clover, 1965) adapted the novel.

Disappointment.