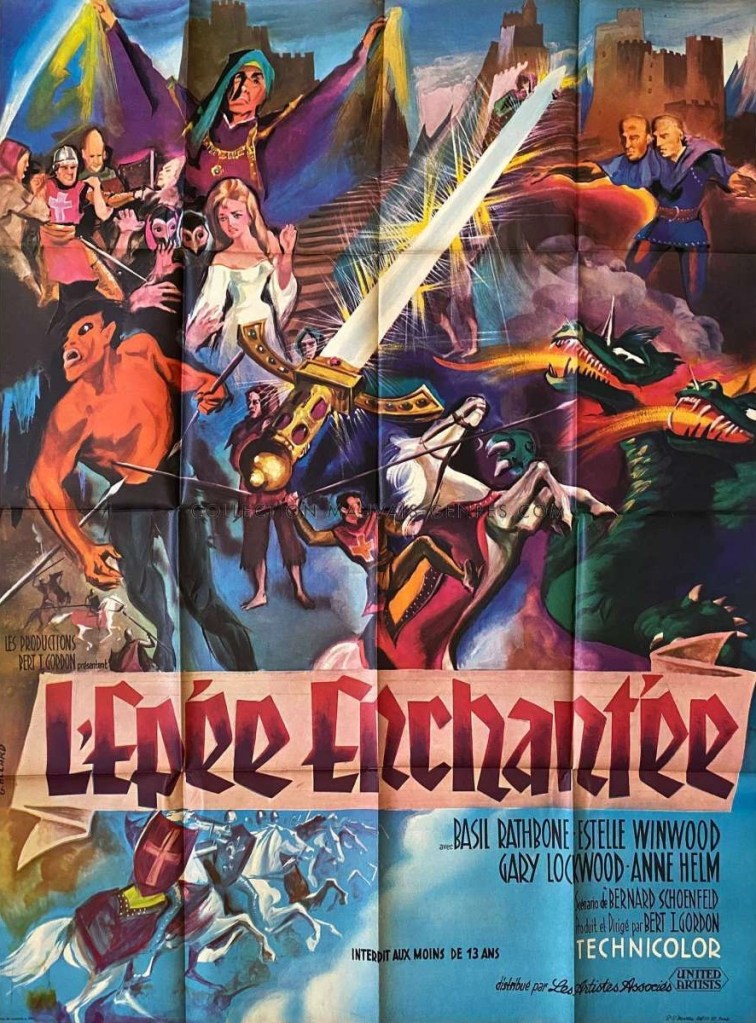

Where’s Ray Harryhausen when you need him? Not much wrong in this fun low-budget adventure that a few doses of Dynamation wouldn’t fix. While it means the monsters don’t cut it – man in mask with a dodgy perm playing an ogre, two-headed dragon whose flames appear superimposed – the rest of it is as up to scratch as you might expect from a genre that relies on exploiting old myths.

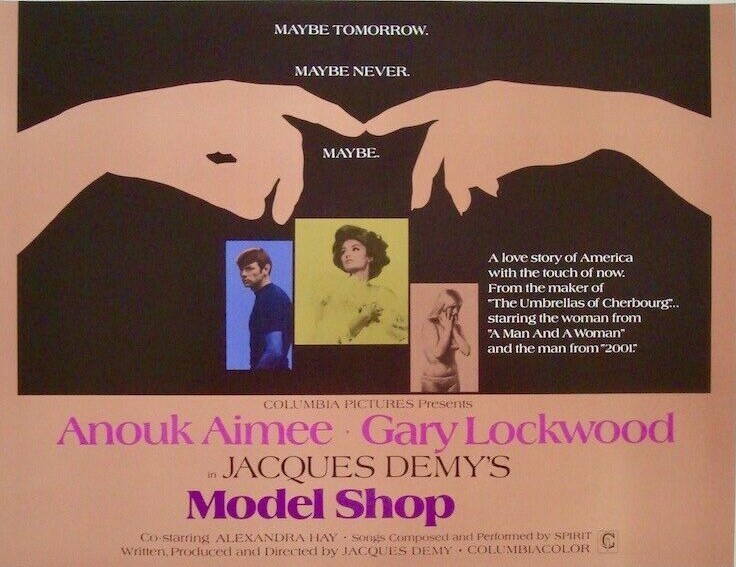

And we do get a look at Gary Lockwood (The Model Shop, 1969) in embryo and Basil Rathbone (The Comedy of Terrors, 1963) having a whale of a time as a villain who somehow (point plot not explained) has lost his magic ring. That means he’s going to strike a deal with loathsome knight Sir Branton (Liam Sullivan) – who happened across it (plot point unexplained) – to kidnap Princess Helene (Anne Helm). He’s somewhat hindered in explaining his plans because his voice is often drowned out by the thunder he can summon just by lifting his arms.

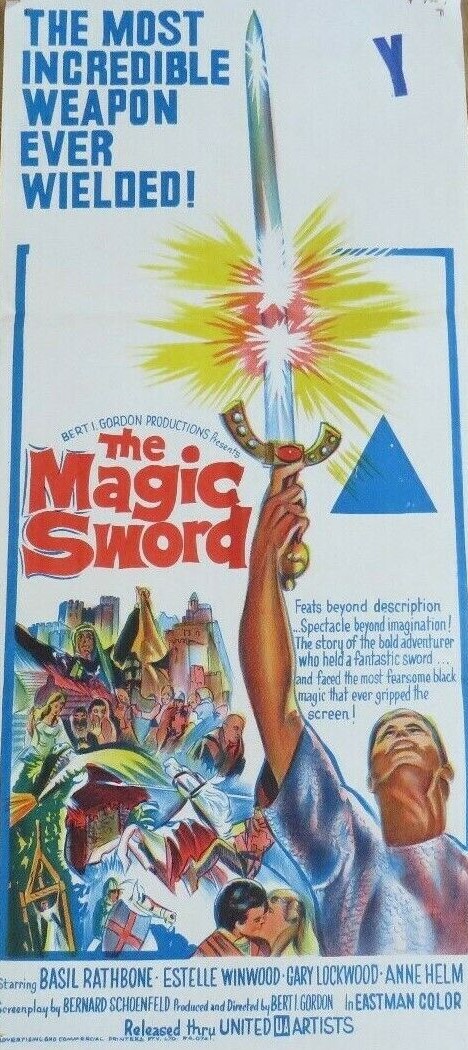

But it’s magic vs. magic as the pair come up against sorceress Sybil’s (Estelle Winwood) adopted son Sir George (Gary Lockwood) who’s stolen a set of enchanted artefacts including the titular sword, armor, a shield and the fastest horse in the world and heads off to rescue fair maiden from the castle of Lodac (Basil Rathbone) where the aforementioned dragon is on a steady diet of consuming a human being (or two, if twins or sisters are to hand) once a week.

Sybil, who seems to exist in some kind of darkroom, constantly lit by red, is a hoot, when not turning herself into a cat, unable to recall spells, not surprising since her memory has to span 300 years. Her coterie includes a chimp who does nothing (what’s the point of that, you might wonder, though perhaps magic is involved in just getting it to sit still) and a two-headed man, both faces speaking the same words at the same time.

There’s a tilt at a magnificent seven scenario as Sir George brings to life six sidekicks, a multi-cultural melange if ever, or a stab at attracting audiences from six different countries if you like. You need to be mob-handed at this game because the bunch, assisted or sabotaged by the accompanying Sir Branton, need to overcome The Seven Curses of Ladoc (the film’s alternative title in various parts), including the ogre and a malodorous swamp, and sure enough those dangers soon cut the motley band down to size.

Meanwhile, the imprisoned princess has watched the dragon eat, and is tormented by dwarves (though the caged elves turn out to be friendlier). There’s going to be two showdowns, not one, since Lodac has no intention of allowing Sir Branton the glory of rescuing said princess and therefore winning her hand in marriage. He is hell-bent on revenge, since the king’s father had burned his sister at the stake as a witch.

The meet-cute if you like is princess and potential rescuer facing each other across a dungeon while tethered by rope to stakes. Sybil does try to help but damned if she can remember the final words of her spell.

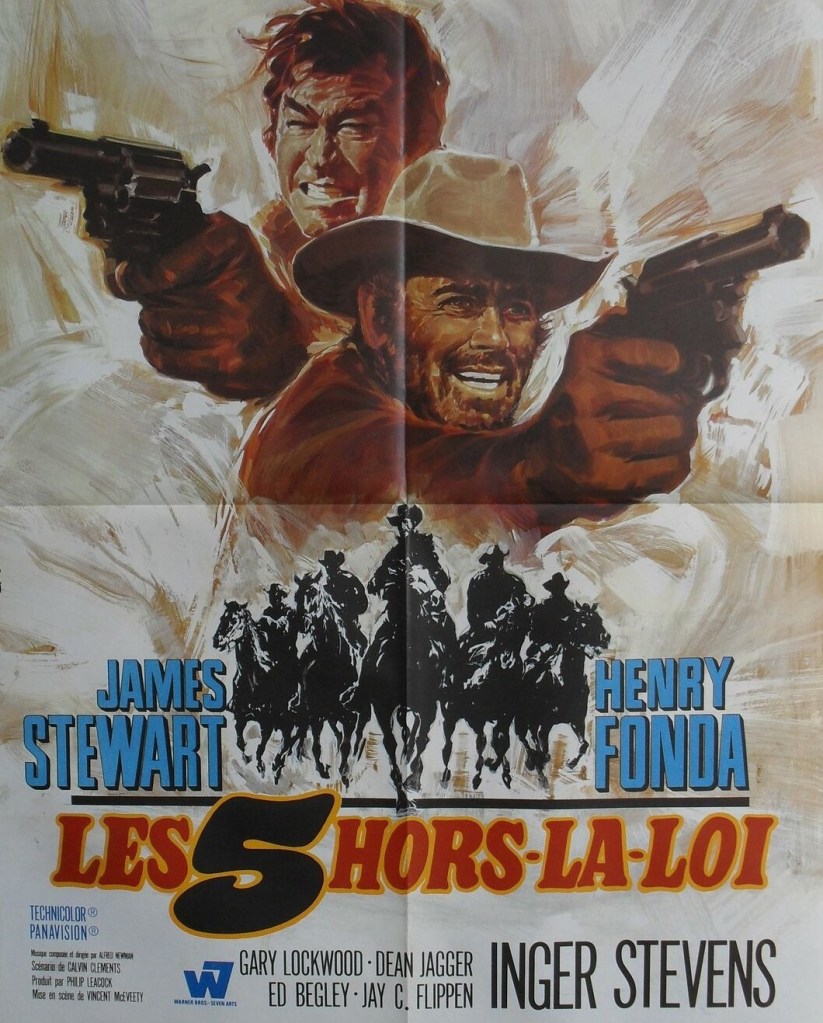

Gary Lockwood, in his first leading role, takes the whole thing seriously, and only made two more films before something in this role and It Happened at the World’s Fair (1963) and Firecreek (1967) tipped off Stanley Kubrick that here was a star in the making for 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). So it does show that no part, however preposterous, is worth turning down.

Basil Rathbone would steal the show – as he should being top-billed – were it not for the fun-loving Estelle Winwood (Games, 1967) as the dotty aunt kind of sorceress. What Hollywood dictat I wonder determined that leading actresses often made their entrance swimming naked in a pool. Anne Helm (The Interns, 1962) doesn’t have much to do except look scared. You might spot Danielle De Metz (The Scorpio Letters, 1967).

With Sybil to dupe, all the curses to overcome and deal with the duplicitous Sir Branton, the pace never lets up. And it’s short (just 80 minutes) so no time for dawdling.

Director Bert I. Gordon (The Amazing Colossal Man, 1957) has been here before with the special effects that appear dodgy to the contemporary eye but were ground-breaking at the time when SFX did not command multi-million-dollar budgets. Screenplay by Gordon and Oscar-nominated Bernard C. Schoenfeld (13 West Street, 1962).

While Harryhausen tales were always redeemed by the special effects, this is perfectly acceptable late-night entertainment when the critical guard is down.