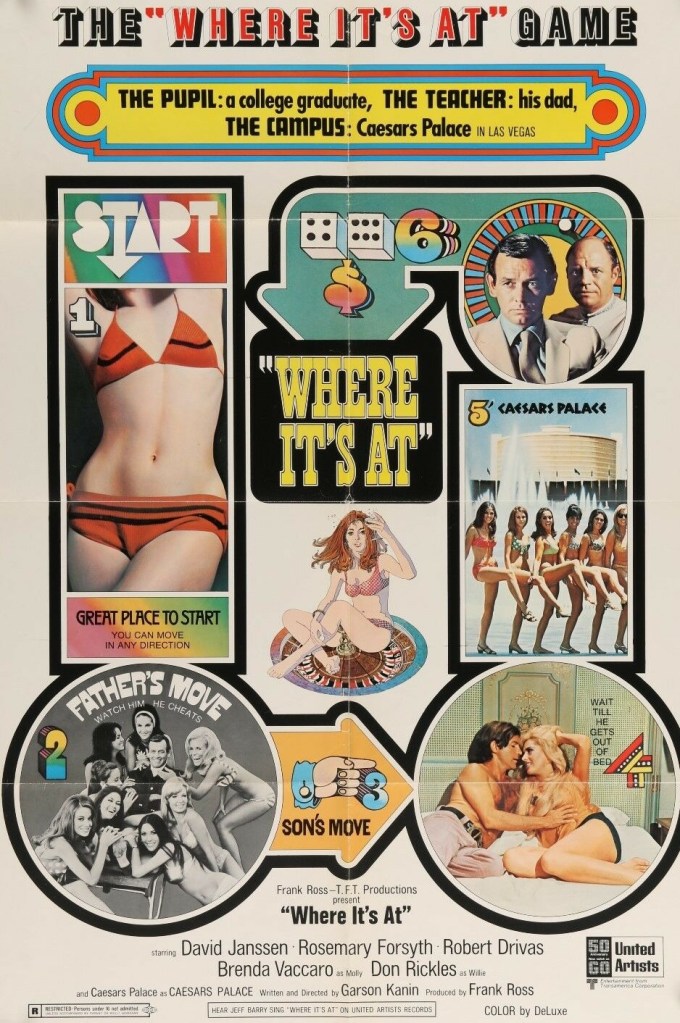

There is probably no more stunning definition of Las Vegas than the brief shot in this otherwise widely-ignored film of a woman playing the slot machines with a baby at her naked breast.

I doubt if anybody has watched this all the way through in the fifty-odd years since its release. And I can see why. I nearly gave up on what I thought was a lame generation gap comedy. But some distinguished directors at the time clearly perceived its value, the flash cuts and overlapping dialog initiated here turning up, respectively, in Sydney Pollack’s They Shoot Horses, Don’t They (1969) and Mash (1970). And as I gamely persevered, I realized it was a different movie entirely, a cross between Succession and The Godfather.

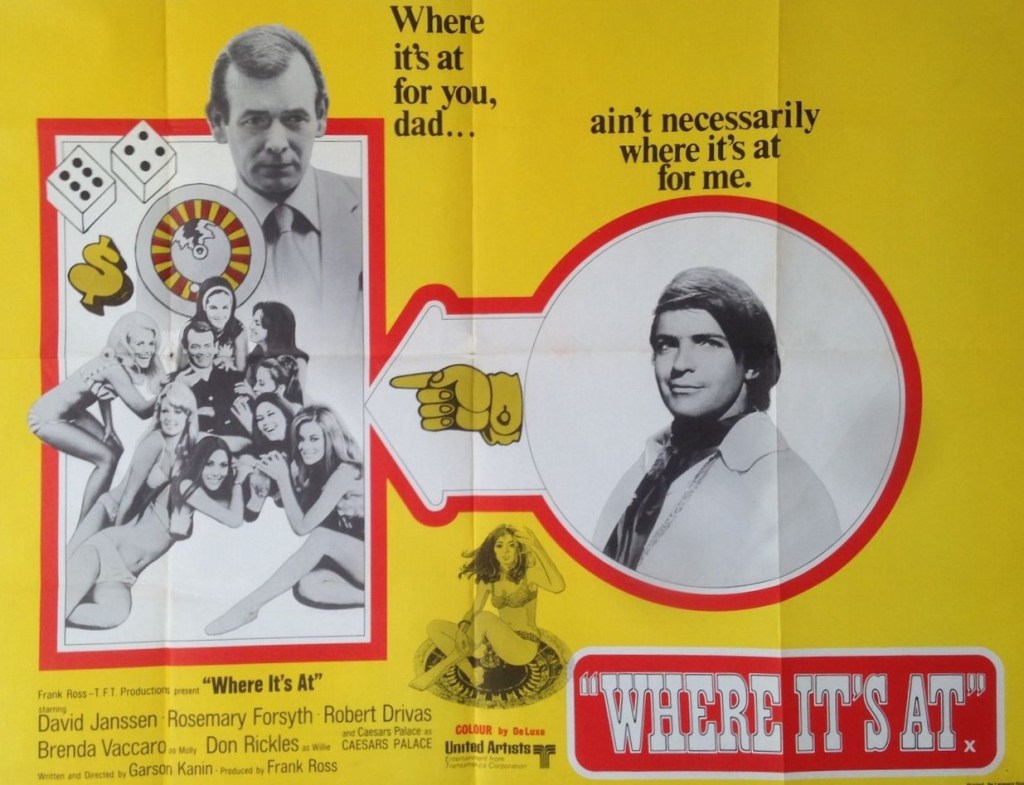

Though saddled with a trendy catchphrase of the period for a title – though making more sense if applied in ironic fashion – the original title of Spitting Image was much more appropriate to the material. As both veteran and new Hollywood directors struggled with understanding the burgeoning counter-culture, youth-oriented efforts of the Tammy and Gidget and beach pictures variety fast fading from view, and Easy Rider (1969) yet to appear, a generational mismatch between Hollywood veterans and younger audiences was in evidence.

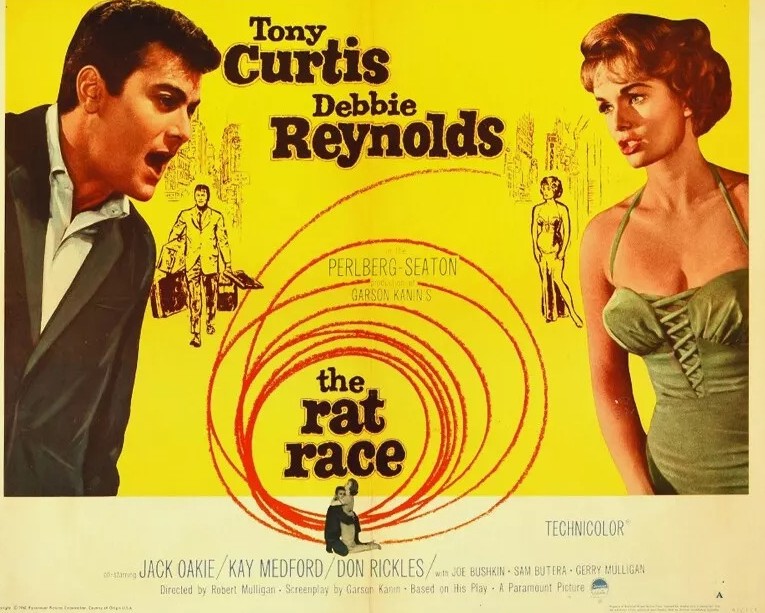

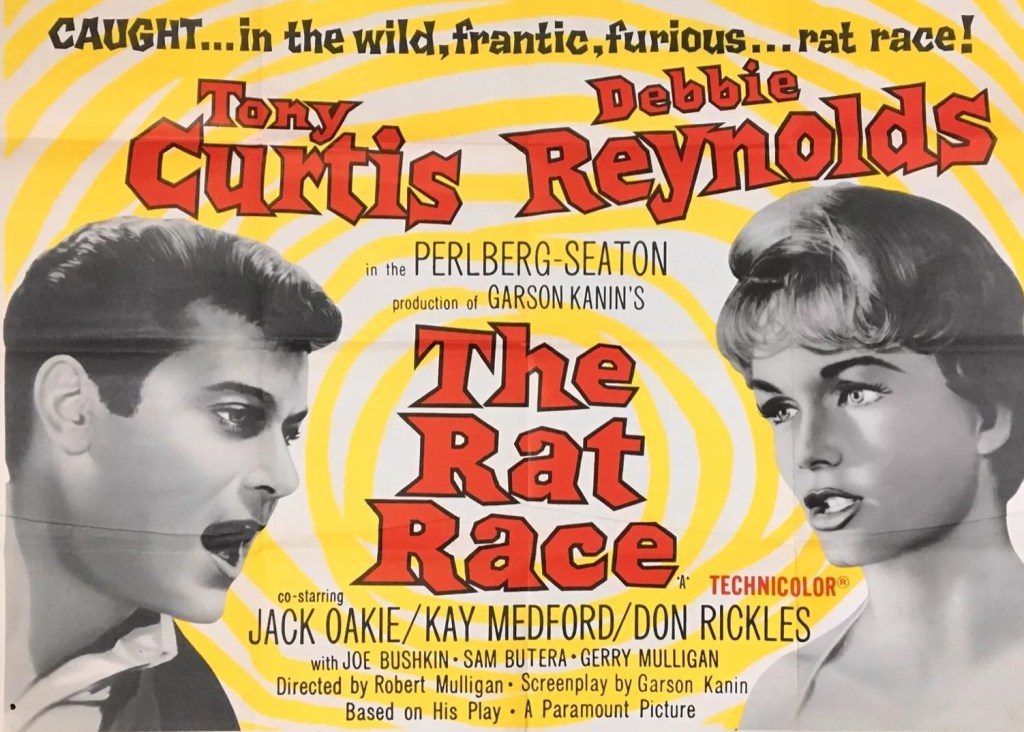

And you would hardly turn to Garson Kanin to capture the zeitgeist. Although acclaimed as a screenwriter, with wife Ruth Gordon responsible for a string of Tracy-Hepburn movies like Adam’s Rib (1949), he had not directed since 1941. The story he wanted to put over – he wrote the script as well – was not an easy sell. So he’s disguised it as a coming-of-age tale exploring the generation gap and as a lurid expose of Las Vegas with behind-the-scenes footage of the reality underpinning the glamour.

It’s pretty clear early on it’s not about some middle-aged parent getting jealous over the amount of sex his child has, for widowed casino owner A.C. (David Janssen) can have as much as he wants courtesy of fiancée Diana (Rosemary Forsyth) – and a wide range of available and eager-to-please showgirls – and certainly far more than the majority of his male customers whose biggest thrill is gawping at topless women on stage. Las Vegas was the epitome of Sin City, at the beginnings of its sacred position in American popular culture where what you got up to remained secret. The representation of the “showgirl” world is less brutal than in Showgirls, but even so an audition includes removing your bra.

A.C. wants to introduce son Andy (Robert Drivas) into the business not realizing he is laying out a welcome mat for a viper. At first Andy is happy to learn the ropes by working in menial positions and wise enough to resist obvious lures like showgirl Phyllis (Edy Williams), whose interaction with him is recorded. However, when like Michael Corleone, he is required to make his business bones – “pay your dues and stop your whining” – by transporting cash skimmed from the business and banked in Zurich back home, where if caught he will have to take the rap, a more calculating and dangerous individual emerges. A.C. has been working a Producers-type scheme where by massaging profits downwards he hopes to panic his investors into offloading their stock cheaply to him.

The ploy works but it turns out his partners have sold their stock to Andy, who hijacked the Zurich cash to pay for it. Rather than chew out Andy, A.C. is delighted at the ruthlessness of the coup, until his son, now holding the majority of shares, takes complete control, easing him out – “If I need you, I’ll send for you.” Andy’s prize could easily include, had Andy showed willing, the duplicitous Diana. However, that’s not the way the picture ends and I won’t spoil the rest of the twists for you.

This is one of the few genuine attempts to show the pressure under which businessmen operate. No wonder A.C. is so glum, barking at everyone in sight, little sense of humor, when the stakes are so high and as with any game of chance you might lose everything. Employing indulgence to insulate himself against emotion, he is surrounded by what he deduces is the best life can offer, driven by mistaken values. Optimism is the automatic prerogative of youth, pessimism the corrosion that accompanies age.

The second half of the picture has some brilliant brittle dialog. Assuming the young man has principles, when his acceptance of the Las Vegas dream is challenged Andy replies, “Who am I to police the party?” In a series of visual snippets and verbal cameos, the film captures the essence of Las Vegas, from the aforementioned woman breast-feeding while playing the slot machines to the telephone call pleading for more money, waitresses hustling drinks, a machine in A.C.’s office rigged to give high-rollers an automatic big payout and leave them begging for more, customers not even able to enjoy meal without a model sashaying up to the table to sell the latest in swimwear, never mind the more obvious tawdry elements.

There’s a superb scene involving a cheating croupier (Don Rickles). Of course, when Martin Scorsese got into the Vegas act, violence was always the answer. A.C. takes a different route, allowing the man to pay off his debt by working 177 weeks as a dishwasher. There’s a neat twist on this when Andy, guessing which way Diana is going to jump, warns “watch out you don’t end up washing dishes.”

David Janssen (The Warning Shot, 1967) gives another underrated performance, gnarly and repressed all the way through until he can legitimately feel pride in his son. Robert Drivas (The Illustrated Man, 1968) is deceptively good, at first coming over as a stereotypical entitled youngster (or the Hollywood version of it) before seguing into a more devious character. Rosemary Forsyth (Texas Across the River, 1966) is excellent, initially loving until casually moving in on the young man when he appears a better prospect than the older one. Brenda Vaccaro (Midnight Cowboy, 1969), in her debut, plays a kooky secretary who has some of the best lines. “Two heads are better than one,” avers Andy. Her response (though Douglas Adams may beg to differ): “Not if on the same person.”

Garson Kanin takes the difficult subject of ruthless businessman and provides audiences with an acceptable entry point before going on to pepper them with vivid observations. This is not a picture that divided audiences – not enough critics or moviegoers saw it to create divergence – but it’s certainly worth another look especially in the light of the shenanigans audiences have welcomed in Succession. And if you remember the pride Brian Cox took when shafted by his son, check out this picture and you will see where the idea came from.

And it’s worth remembering that the defining youth-culture movie of 1969, Easy Rider, was actually about two young businessmen. The fact that their product was drugs didn’t make them any less businessmen. The idea that what a young buck “digs” the most is making money rather than peace and love seemed anathema to critics as far as Where It’s At went but not Easy Rider.

To be sure, none of the characters are likeable. Maybe likability was an essential ingredient of 1960s movies, but we’re more grown-up now. Compared to the the horrific characters populating The Godfather and today’s Succession, these appear soft touches. One critic even pointed out that The Godfather did it better without seeming to notice that Where’s It’s At did it first. And there’s certainly a correlation between Andy turning his nose up at his father’s business and Michael Corleone showing similar disdain until the chips are down and the old cojones kick in.

Critics who complained this had little in common with the Tracy-Hepburn pictures missed the point. The Tracy-Hepburn films were always about power, in the sexual or marital sense. Kanin has merely shifted from a male-female duel to that of father-son.

Not currently available on DVD or on streaming, but easy to get hold of on Ebay and YouTube has a print.