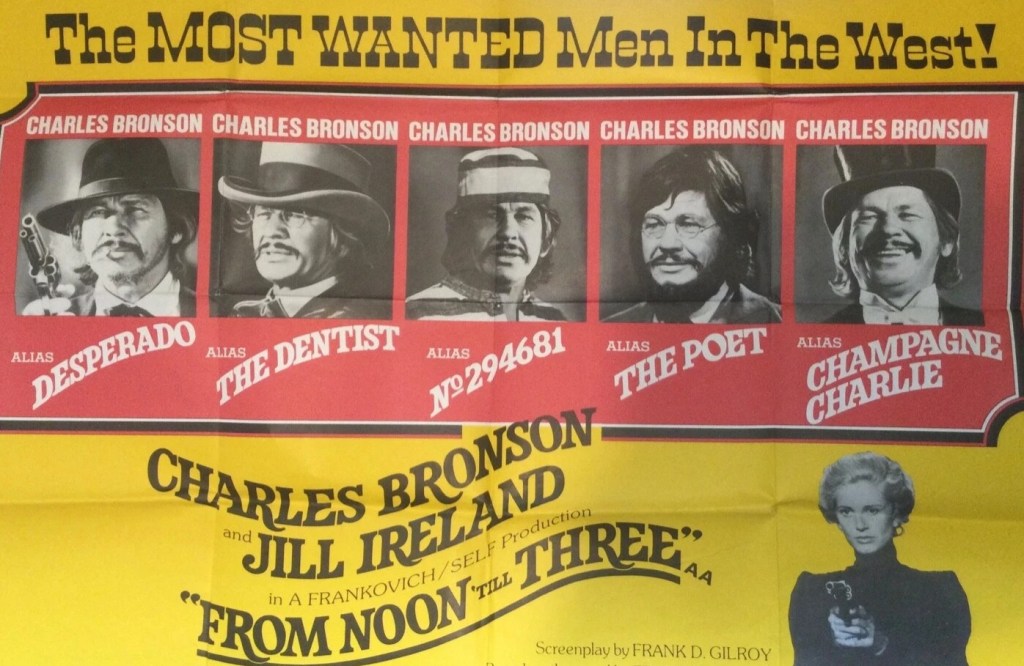

Charles Bronson in a feelgood movie? Charles Bronson the romantic comedy lead? Charles Bronson’s character impotent? The hell you say!

Certainly, Bronson’s boldest role, and if the original concept had played out the way audiences might have expected, the star’s career might have taken the kind of pivot afforded Arnold Schwarzenegger when he took on Twins (1988). But a third act which probably baffled audiences half a century ago plays straight into the hands of the contemporary filmgoer and spins such a twist – almost a horror version of “print the legend” – that nobody has ever invented a better one.

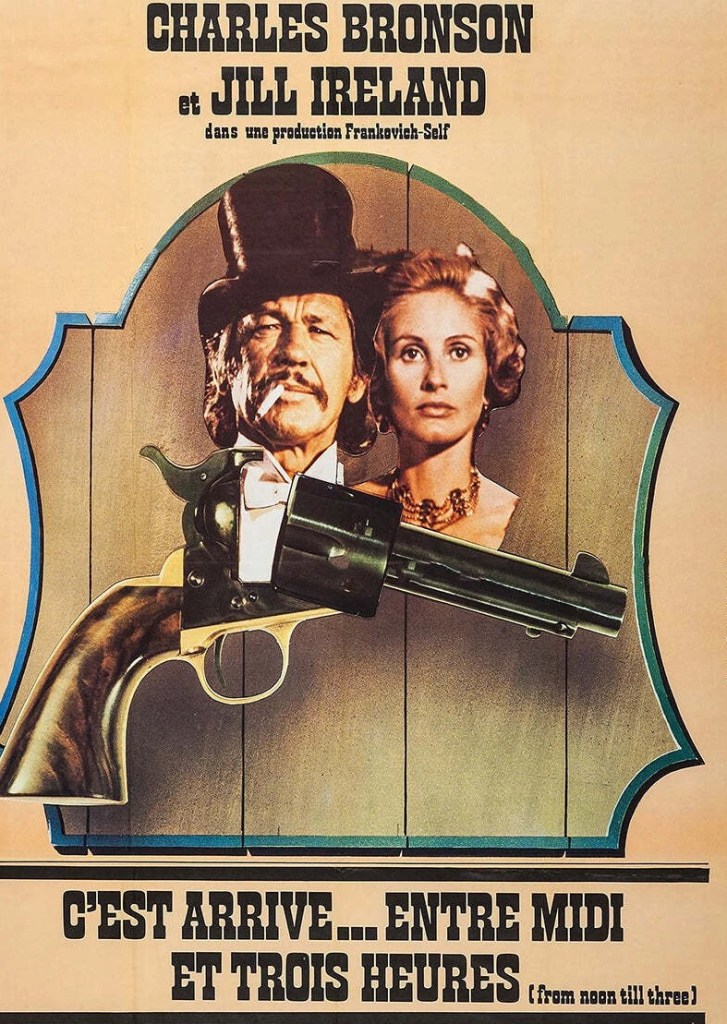

This isn’t just Bronson as you’ve never seen him before but it’s also Jill Ireland in the role of her life, proving not just that she can act but putting on a brilliant performance.

So, this isn’t like any Charles Bronson character you’ve ever seen, light years away from the monosyllabic justified or unjustified killers he had hitherto portrayed for most of the decade. He’s not even the leader of the gang of outlaws and has a decidedly cowardly streak. And this isn’t Jill Ireland, his wife, either, in some punched-up supporting role. Here she essays her inner Katharine Hepburn or prissy Maggie Smith and engages in the kind of male-female verbal duel that hasn’t been seen since The African Queen (1952).

When his horse pulls up lame Graham Dorsey (Charles Bronson) decides not to accompany his four outlaw buddies on a bank robbing expedition and despite the prospect of “borrowing” a horse from rich widow Amanda Starbuck (Jill Ireland) he goes along with her pretense that no such beast exists because he’s had a presentiment that the heist will go awry. The gang agree to pick him up on their return at a tension-sodden three o’clock – hence the title, a mild play on High Noon (1952).

Amanda is more than capable of dealing with his kind despite him spinning her a tale of having lost a similar mansion to her grand three-storey affair after the Civil War and being widowed for seven years and so depressed at his impotency he’s contemplating suicide.

In the way of opposites attracting, one thing leads to another and soon they are waltzing, dressed up to the nines, in her elaborate rooms and taking a dip au natural in a lake. When word comes back that the robbers have been caught and are all set to hang, much against his natural inclination not to jeopardize his newfound love, he agrees, at her behest, to go save them. Although he intends doing nothing of the sort and simply lying low, he is pursued by a posse and only evades capture by swapping clothes with a dentist he captures.

And then the tale deftly switches. The posse kills the real dentist. Seeing only his blood-drenched clothes at a distance, Amanda believes it’s Graham. Meanwhile, he’s locked up after being convicted of the dentist’s crimes. She’s so enthralled by the unlikely romance that she writes a book about it that turns into the kind of publishing phenomenon that triggers tours of Graham’s grave and the house where it all happened.

When Graham is released, you expect the sting in the tale will be that she’ll have gone off and married someone else. But she hasn’t. Except she doesn’t recognize him. Because in the writing she transformed him into a much taller more handsome figure and her imagination can’t deal with reality. Any time he reminds her of an intimate moment, she cries out “it’s in the book.” Finally, somewhat rudely, he does convince her but then, afraid of letting down the millions of fans captivated by the legend, rather than reviving their romance, she kills herself so the story cannot be challenged.

Worse, nobody believes Graham and he is accused of being a fraud and ends up in a lunatic asylum. Charles Bronson the madman, you didn’t see that coming I bet.

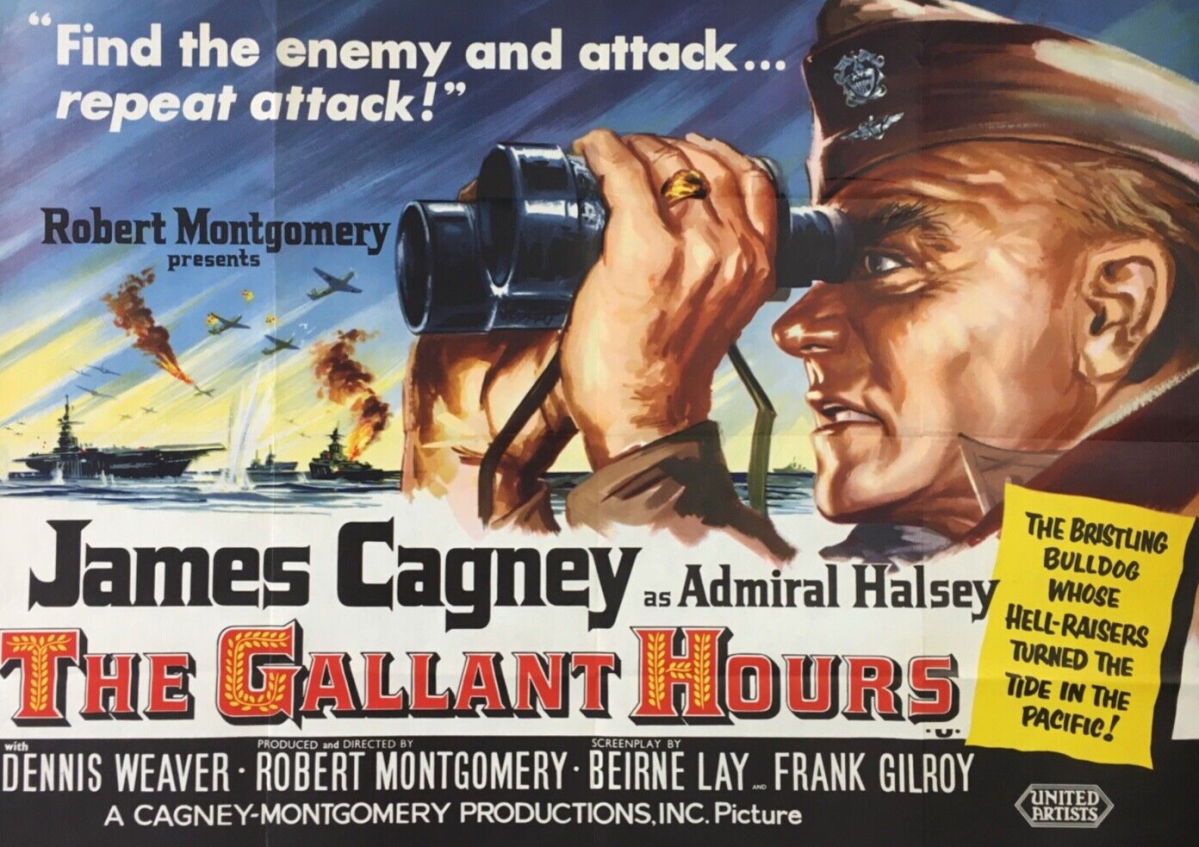

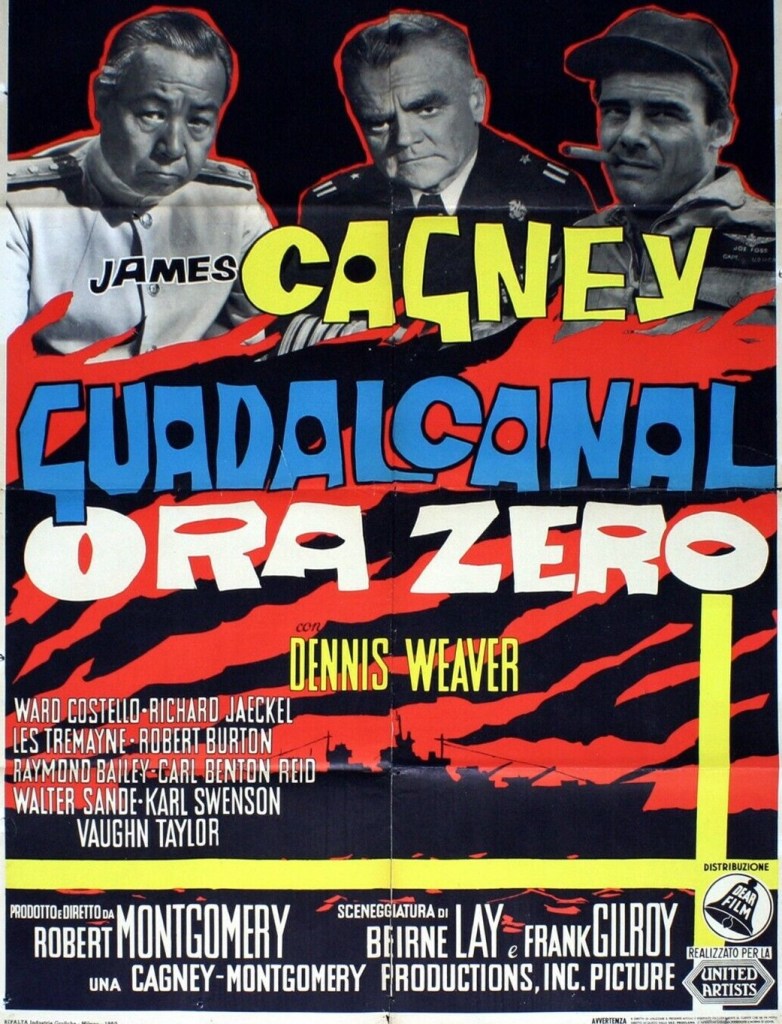

As you can tell from the posters, United Artists had no idea how to sell it and it lacked the single immediately visually-appealing gag of Twins, so it was a rare flop at this point in Bronson’s career. But a third act that was viewed as somewhat deranged satire has, in the half century since, now come into its own when questions about identity and point of view and “your own truth” and “recollections may vary” and imposter narrative and reality reinvention and fake news are endemic. In this case “print the legend” comes to haunt Graham.

But what was a flop in 1976 deserves reassessment and should be welcomed by a contemporary audience more able to deal with the sudden shift in tone. It might also put to rest the notions that neither Charles Bronson (Once Upon a Time in the West, 1969) nor Jill Ireland (Rider on the Rain, 1970) could act. This is a wonderfully spirited double act and had the movie been remotely successful might have set them up as a latter-day Tracy-Hepburn. I should note in passing a wonderful tune, “The Trouble With Hello Is Goodbye,” lyrics by Alan and Marilyn Bergman and music by Elmer Bernstein. Had the movie not been so quickly dismissed, that had all the making of a torch song.

Writer-director Frank D. Gilroy (Desperate Characters, 1971) has produced some scintillating dialog as well as bringing out the best in the couple. As clever on the spoofery front as Blazing Saddles (1974) and Support Your Local Sheriff (1969) but with a harder satirical edge.

I chuckled all the way through. It was a delight to see Bronson and Ireland playing such refreshing characters and the rom-com element worked out really well. So two bangs for your buck – a reinvented Bronson in the kind of role you never thought he could manage, and the kind of satire that hits home today.

Put aside all thoughts about what Charles Bronson and for that matter Jill Ireland can do or should do and sit back and enjoy this unexpected gem.

You can catch it on Amazon Prime.