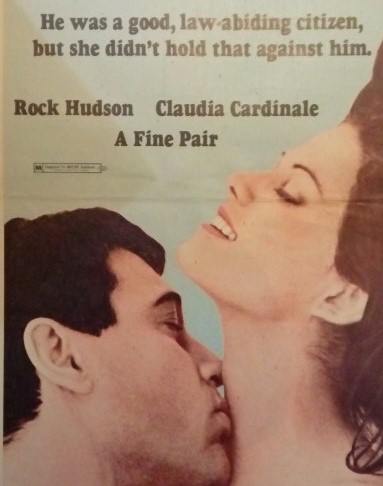

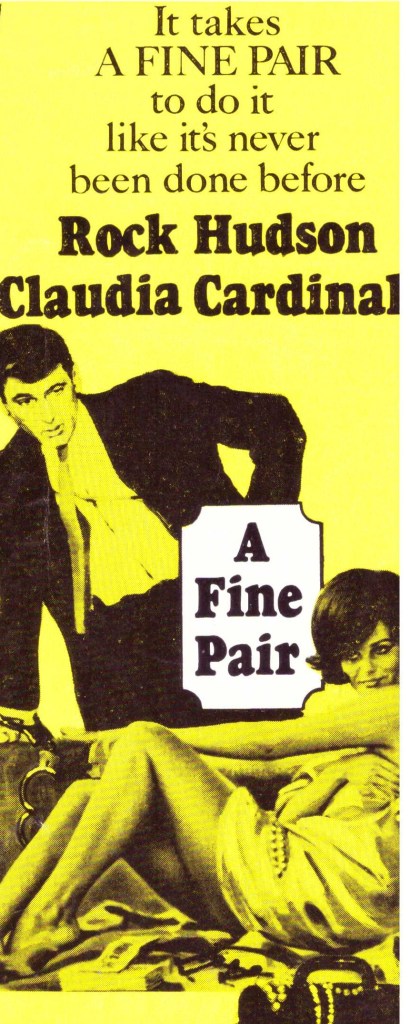

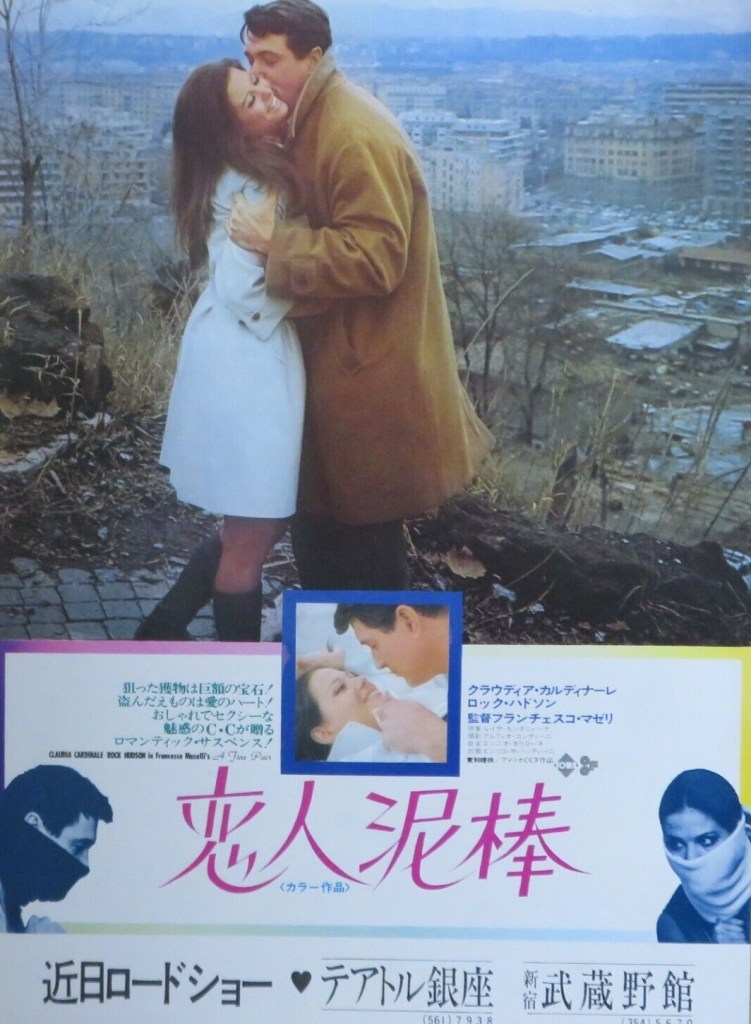

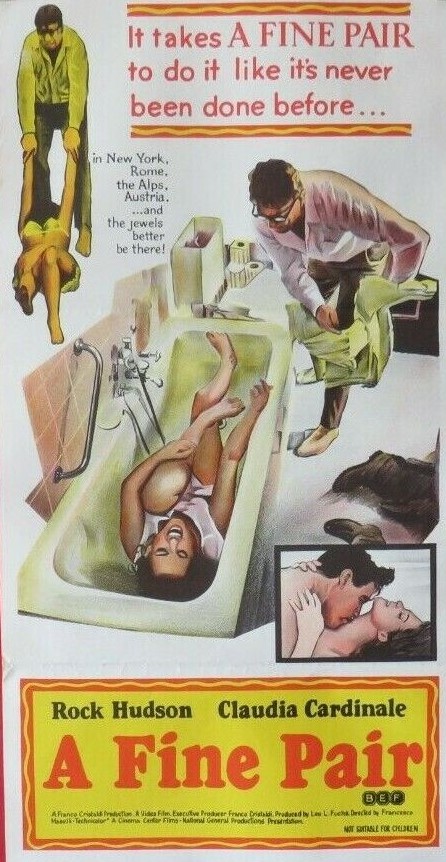

Essentially an Italian take on the slick glossy American thriller in the vein of Charade (1963), Arabesque (1966) and of course Blindfold (1966) which previously brought together Rock Hudson and Claudia Cardinale. Produced by Cardinale’s husband Franco Cristaldi, directed and co-written by Francesco Maselli (Time of Indifference, 1966), it is a cute variation on the heist picture. Fans accustomed to seeing the more sultry side of the Italian actress (as in The Professionals, 1966) might be surprised to see how effective she is in more playful mood apart from one scene where she strips down to bra and pants. The other major difference is that in her American-made films, Cardinale is usually the female lead, that is, not the one driving the story, but here she provides the narrative thrust virtually right up until the end.

The twist here (as in Pirates of the Caribbean nearly four decades later) is that the bad guy (in this case bad girl) wants to return treasure rather than steal it. Esmeralda (Claudia Cardinale) arrives in New York to seek the help of Capt. Mike Harmon (Rock Hudson), an old family friend, a stuffy married American cop who even has a timer to tell him when to take his next cigarette. She has come into jewels stolen by an internationally famous thief and wishes to return them to a villa in the Alps before the owners discover the theft. The bait for Harmon is to try and apprehend the guilty party.

The audience will have guessed the twist, that she is not breaking in to return jewels, but once Harmon, through his police connections, has been shown the alarm systems, to deposit fakes and steal the real thing. So Harmon has to work out an ingenious method of beating three alarm systems, one of which is heat-sensitive, the whole place “one big safe.”

Most of the fun comes from the banter between the principals and the is-she-telling-truth element essential to these pictures. “I lied – and that’s the truth,” spouts Esmeralda at one point. I disagree with a common complaint of a lack of chemistry between Hudson and Cardinale. What the film lacks is not enough going wrong such as occurred in Man’s Favorite Sport (1962), which makes the audience warm to the otherwise rigid Hudson, or as seen in Gambit (1966) where Michael Caine played a similar stand-offish character. Cardinale is terrific in a Shirley MacLaine-type role, as the playful foil to the uptight cop, and who, like MacLaine in Gambit, knows far more than she is letting on.

What does let the film down is that it is at cross-cultural cross-purposes. As mentioned, this is an Italian film with Italian production values. The color is murky, way too many important scenes take place outside, but, more importantly, the actual heist lacks sufficient detail, and post-heist, although there a few more twists, the film takes too long to reach a conclusion. But for the first two-thirds it is a perfectly acceptable addition to the heist canon, the script has some very funny lines, Cardinale is light, charming and sexy.

The American title of this film was Steal from Your Neighbor, which is weak. A Fine Pair while colloquial enough in America has, however, an unfortunate meaning of the double-entendre kind in Britain.

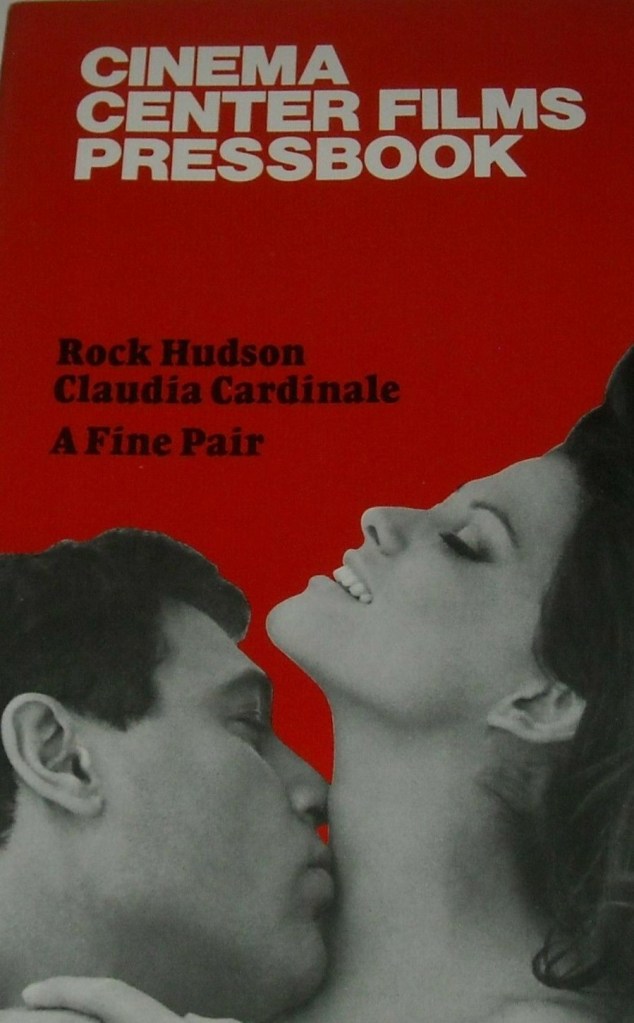

Lack of films being released – these days due to the pandemic – is not new. A Fine Pair was made during a time of low production. But there was a sickening irony in the story of this film’s production. It was financed by the short-lived Cinema Center owned by the American television network CBS. When television was in its infancy, American studios had been barred by the Government from becoming involved in the new media. CBS got into movie production after studios had suffered from another governmental policy reversal.

In 1948 the Paramount Decree prohibited studios from owning cinemas, a move which led to the end of the studio system and decimated production. The most sacrosanct rule of American film regulations was that studios could not own movie houses. Everyone assumed that applied the other way until in the early 1960s cinema chain National General challenged the ruling.

By this point, production was so low that exhibitors were crying out for new product so the government relented, much to the fury of the studios. That opened the door for television networks like CBS and later ABC (Charly, 1968) to enter movie production. And now, of course, studios have re-entered the exhibition market as have, once again, television companies.

Entertaining enough and the pair have enough charisma to see it through.