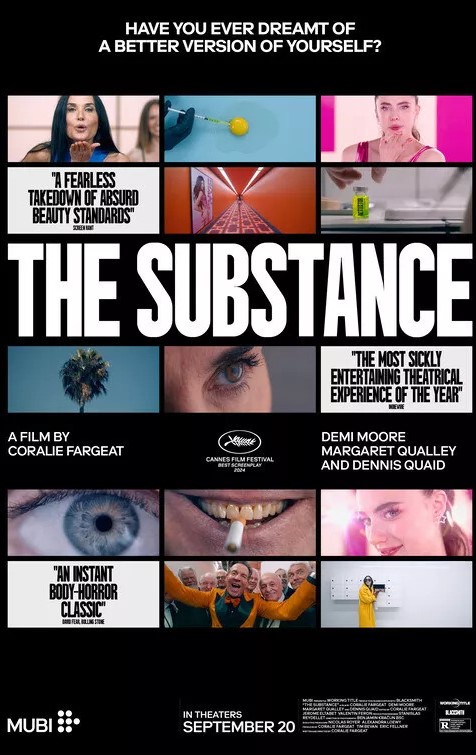

Like Tar (2022) suffers from stylistic overkill and outstays its welcome by a good 30 minutes, but otherwise a perfect antidote to Barbie (2023). While not entirely original, owing much to the likes of The Picture of Dorian Gray and The Stepford Wives and the doppelganger and split personality nrrative nonetheless a refreshing take on the ageing beauty syndrome. Shower fetish might be a homage to Brian DePalma and except that the movie is directed by Frenchwoman Coralie Fergeat (Revenge, 2017) we might be lambasting its rampant nudity for misogynistic reasons.

On the plus side, everything else about it feels new. The whole story plays out like a demonic fable, the participants only caught out because, in their greed, they refuse to play by the rules. But like all the best horror films this occupies its own world. Whoever offers this free drug and the chance to relive your life through the best possible you is a monosyllabic voice at the end of a telephone. Not only is there gruesome rebirth but a stitching-up process. The black market drug at the center of the tale can only be accessed in a deadbeat part of Los Angeles by crawling under a door, but then, suddenly we’re in a pristine room and the various constituent parts of the substance are laid out on the Ikea model with easy-to-follow instructions.

After surviving a horrific automobile accident, onetime movie star Elizabeth (Demi Moore), reduced to breakfast television exercise guru, is passed a mysterious note by an incredibly good-looking young man that takes her down this particular rabbit hole. Like Eve’s forbidden fruit or Cinderella’s toxic midnight, there’s a catch to reliving her beautiful youth. She must switch back “without exception” to her original persona every seven days.

Of course, that’s too much to ask, and as the double named Sue (Margaret Qualley) steals minutes then hours and days the effect is seen on Elizabeth, a monstrous aged finger appearing in her otherwise acceptable hands first sign that these rules cannot be broken. Warning that there are two sides to this singular personality goes ignored. Instead of acting in concert each prt of the split personality conspires againt each other until entitlement spills over into abhorrent violence.

Apart from the initial rebirth squence, and the toothless section, the best scenes are more toned down, in one Elizabeth is faced with an alternative future, the other when she re-does her make-up four times for a date, unable to decide on which face she wishes to present.

Demi Moore (Disclosure, 1994) is being touted as a shoo-in for an Oscar nomination, but that’s mostly on account of her willingness to appear without makeup and for long sections without clothing. I’m not convinced that there’s enough heartfelt acting beyond the bitterness that was often her trademark. Margaret Qualley (Poor Things, 2023) isn’t given much personality to deal with except for exuding shining beauty and horror when it starts to go wrong.

All the males are muppets, it has to be said, wheeler-dealer Harvey (Dennis Quaid) the worst kind of obnoxious male. But this doesn’t feel much like a feminist rant but a more considered examination of refusal to accept oncoming age. Everyone has the kind of vacuous personality that’s endemic in presenting the best face (and body) to the viewing (television, big screen) public.

The movie plays at such a high pitch that most of the time you can ignore the deficiencies, but the 140-minute running time is at odds with hooking a contemporary horror audience and the gore at odds with hooking the substantial arthouse crowd required to generate the returns needed to pay back acquisition rights. None of the characters has any depth, little backstory, virtually nothing in the way of the usual confrontation with others in their lives, but then Elizabeth already lives a life of isolation, clearly lamenting her longlost fame and the attention it brings.

This won at Cannes for the script and not the direction and that feels about right. Great idea in ultimately the wrong hands, too much of the repetition that was so annoying in Tar and the determination to make every single shot different, a movie beaten into style every inch of its running time.

Coralie Fergeat has a triumph of some kind on her hands, but one that might struggle, due to excessive length, to find an audience. Not sure, either, why tis is being sold as comedy-horror, a peculiar sub-genre in the first place to make work, but I don’t remember laughing once.

However, like Saltburn (2023) this has a good chance of attracting the young crowd via word-of-mouth, the kind who are just waiting to find their own cult material.

Both facinating and repellant.