Richard Greene had been a childhood idol as that dashing hero Robin Hood in long-running British television series (The Adventures of Robin Hood, 1955-1960) and movie Sword of Sherwood Forest (1960) so I was rather at a loss to discover that his career appeared to stumble thereafter. Only one movie in seven years and then a short stint as the hero in The Blood of Fu Manchu (1968) and The Castle of Fu Manchu (1969). What I hadn’t realized given his eternal youthful demeanor was that he was already approaching 40 when he first donned the tights for Robin Hood and that he was coming to the end of a reasonable stint as a leading man in both Hollywood and domestically.

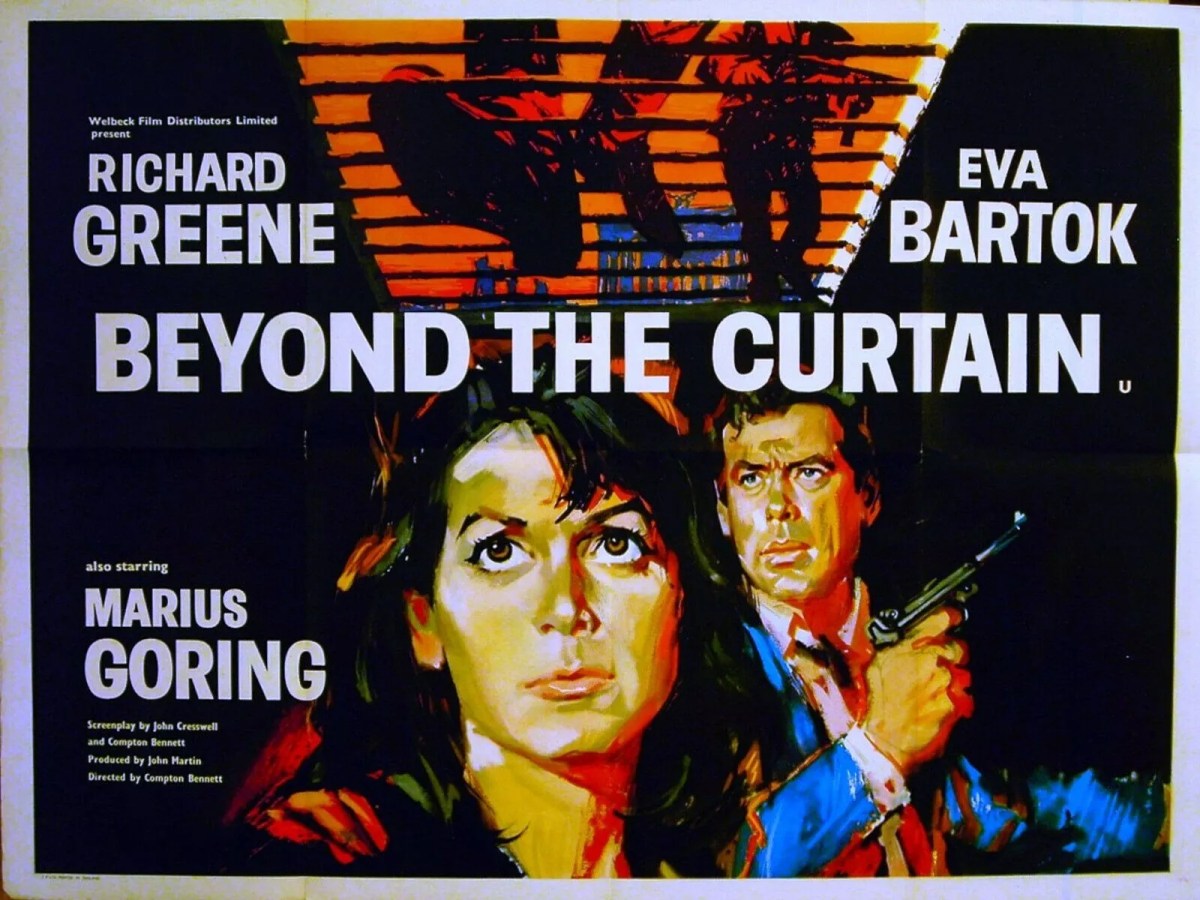

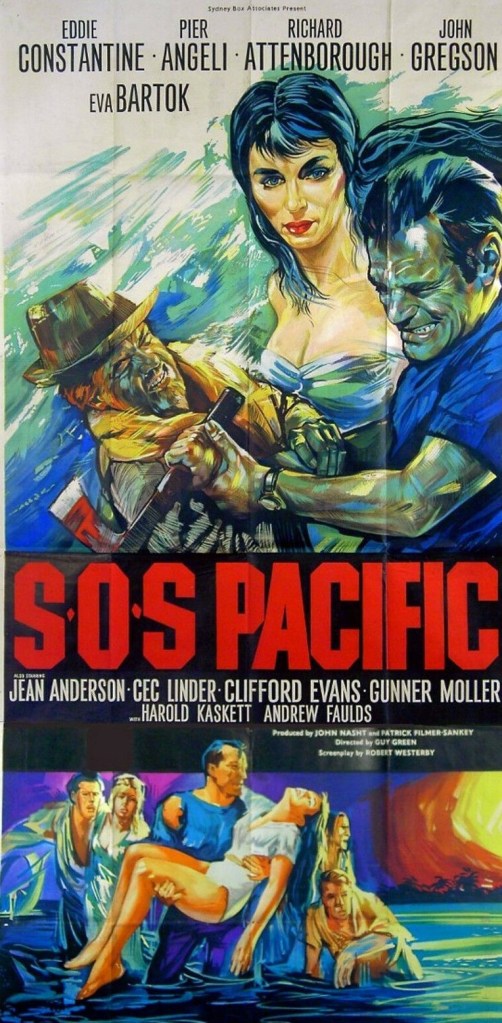

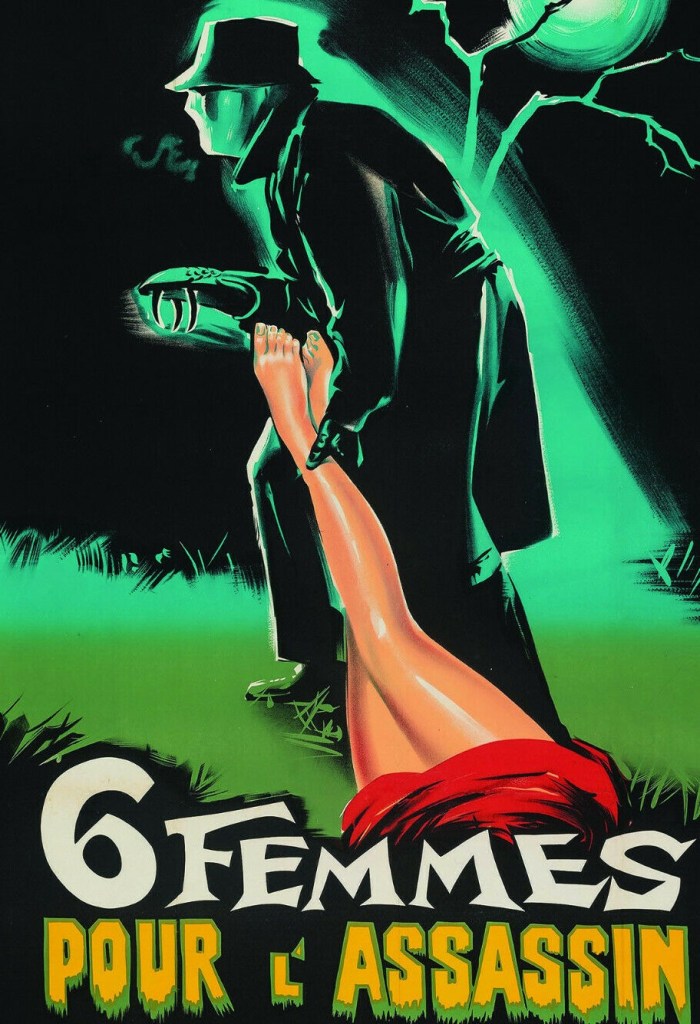

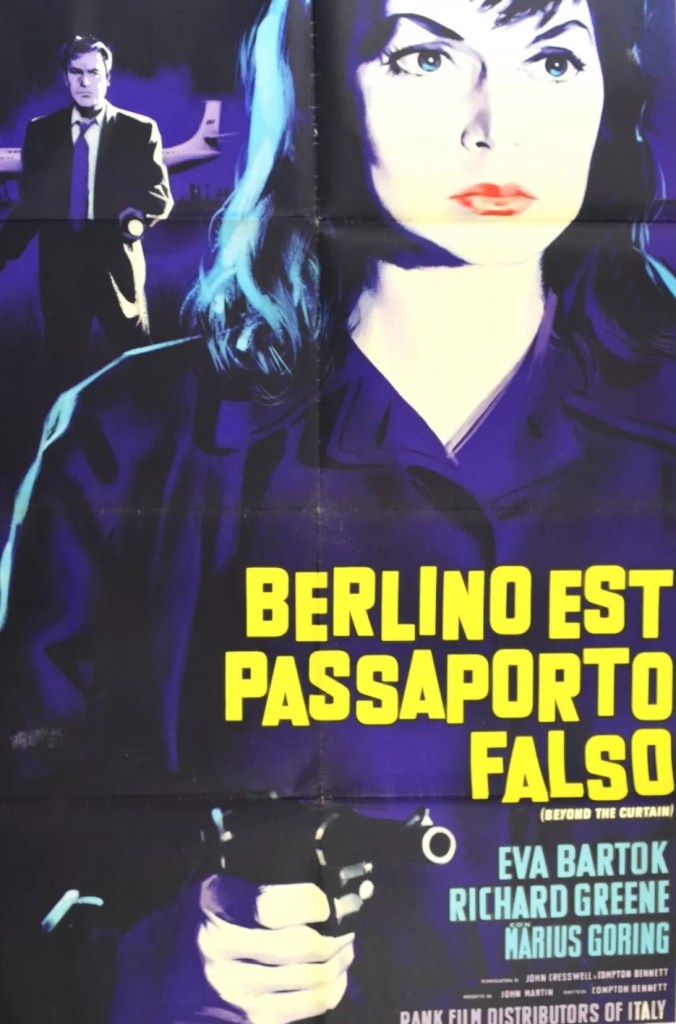

So I shouldn’t really have been surprised that he turned up in this Cold War B-picture. Precisely because he was the star the movie didn’t make the inroads it should have done, given the subject matter and the sensitive playing of Hungarian female lead Eva Bartok (Blood and Black Lace, 1964) whose career was equally foundering after a promising start as Burt Lancaster’s squeeze in The Crimson Pirate (1951).

Audiences were probably baffled by the technicality on which the story pivots. As the Cold War begins – the titular Curtain is The Iron Curtain – air space was as important a national border as land and venturing into foreign air space was construed as deliberate provocation.

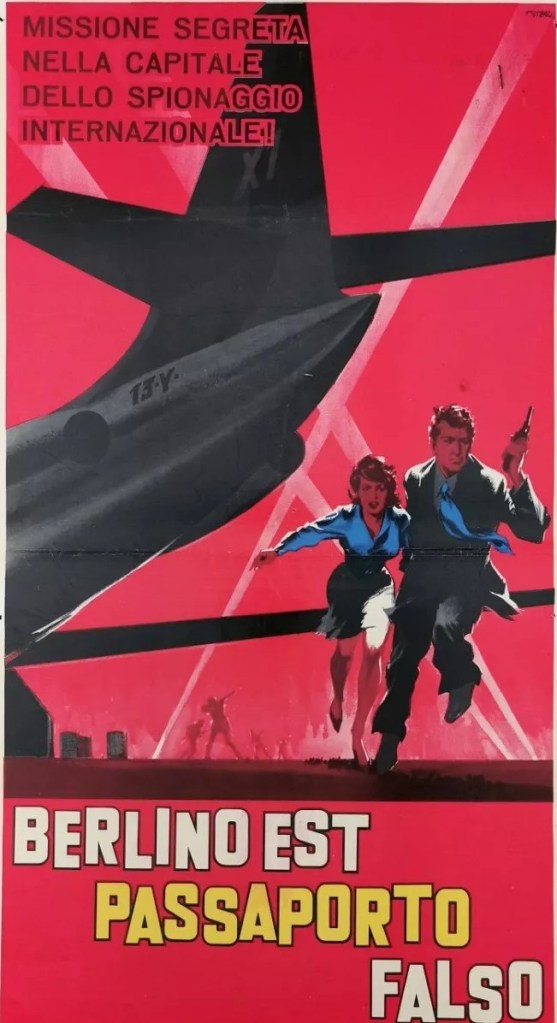

East German stewardess Karin (Eva Bartok), a refugee in Britain from her home country, is arrested when her airplane touches down in East Germany after losing its way in a storm. Pilot fiancé Capt Jim Kyle (Richard Greene), who is let go by the Soviet-influenced authorities, returns to East Germany to try to rescue her.

This resonates more than it did at the time when the Berlin Wall was not yet in existence and the Cold War consisted more of saber-rattling than anything as perilous as the Cuban Missile Crisis. And there’s a definite Kafkaesque tone. Karin is treated as a traitor for attempting to flee her native land and is equally used as bait by her captors to attempt to draw out of hiding her dissident brother Pieter (George Mikell). Outside of Kyle, there’s a sense of romantic revenge, old friend Hans (Marius Goring) now leading the forces hoping to entrap her brother.

There’s plenty of the usual escape ploys, and the atmosphere has noir-antecedents with lighting that exploits shadow and night. And while the thriller aspects work well enough, especially the exciting climax in a tunnel, they carry less impact than the emotions. Karin is terrified of not just being held against her will and interrogated by the fierce secret police, but the prospect of repatriation – or more likely imprisonment – in a country she now despises and had managed to escape is proof that you can’t go home again.

If you remember the scene in Doctor Zhivago (1965) of Omar Sharif after the war returning to his palatial apartment and finding it filled up with other occupants and his family relegated to a very small space, this is its precedent. Karin’s family home is ruled by a sinister landlady-cum-busybody-cum-informant and her suicidal mother (Lucie Mannheim) lives in the attic and suffers delusions. The despair of living in a totalitarian regime comes across very well.

While reminiscent of elements of The Third Man (1949) and thoroughly overtaken in the espionage genre by the likes of The Spy Who Came in from the Cold (1965) and The Quiller Memorandum (1966), this makes it mark by concentrating on entrapment and lack of freedom.

Richard Greene is in his element as the dashing hero, but he’s outshone by Eva Bartok who has much more to lose.

Final feature of British stalwart Compton Bennett (King Solomon’s Mines, 1950) who injects occasional style into proceedings. Written by the director and John Cresswell (Spare the Rod, 1961) from the bestseller by Charles F Blair and A.J. Wallis.

More thought-provoking than you might expect.