Desultory spy thriller with over-complicated story that’s worth a look mostly for the performance of Alex Cord (Stiletto, 1969). I can’t say I was a big fan of Cord and I certainly didn’t shower him with praise for his role as a disillusioned Mafia hitman in Stiletto. But now I’m wondering if I have been guilty of under-rating him.

Normally, critics line up to acclaim actors if they deliver widely differing performances – Daniel Day-Lewis considered the touchstone in this department after Room with a View and My Beautiful Launderette opened in New York on the same day in 1985. But usually screen persona rarely changes, amounting to little more than a heightened or amalgamated version of the actor’s character or features. Once Charles Bronson, for example, started wearing his drooping mustache he was never seen without. Actors may grow old, but never bald.

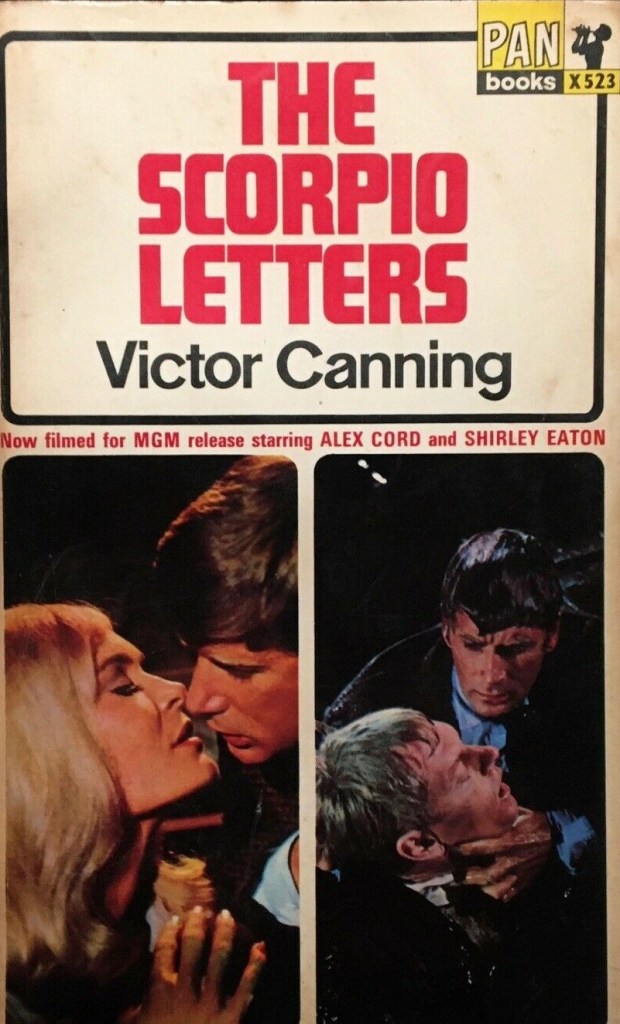

The macho mustachioed Cord of Stiletto is nowhere in sight. In fact, in The Scorpio Letters minus moustache and resisting attempts to reveal his musculature, he is almost unrecognizable. In this picture Joe Christopher (Alex Cord) is flip, resentful, thoughtful, occasionally pedantic, more natural than many of the crop of Hollywood new stars being unveiled at the time, and for once as a transplanted American in London rather scornful of British traditions. There’s a realistic flourish here, too, he is so poorly paid – and on a temporary contract – that he has to take the bus. And although he is an ex-cop fired for brutality, that level of violence ain’t on show here. Virtually the opposite of the character Cord created for Stiletto, I’m sure you’ll agree. So full marks for versatility and talent.

Unfortunately, the rest of the movie is not up to much, at the very bottom of the three-star review category, almost toppling into two-star territory. Christopher is investigating the death of a British agent who was the subject of a blackmail attempt. By coincidence – or perhaps not – another part of British Intelligence is investigating the same death and this brings Christopher into contact with Phoebe Stewart (Shirley Eaton) and eventually they work together to unravel a list of codenames and uncover the conspiracy with a bit of risk to life and limb.

But the pay-off doesn’t work despite all the exposition attempting to build it up and you’re left with a kind of drawing-room drama rather than exciting spy adventure. It’s determinedly London-centric with red buses, red postboxes, Big Ben, and The Horse Guards all putting in an appearance. The scene shifts to Paris and Nice without a commensurate heightening of tension. Despite a couple of neat scenes – a chase held up behind a wedding party, an irate German chef, an interrogation in a wine cellar – it’s much too formulaic.

Cord apart, Shirley Eaton (Goldfinger, 1964) adds some glamour, but her rounded portrait depicts a character with warmth rather than oozing sex. This is the kind of film that should be awash with character actors and up-and-comers but I recognized few names except for Danielle De Metz (The Karate Killers, 1967), Oscar Beregi (Morituri, 1965) and Laurence Naismith (Jason and the Argonauts, 1963).

One-time top MGM megger Richard Thorpe (The Truth about Spring, 1965) was coming to the end of a distinguished career which had included Ivanhoe (1952) and Knights of the Round Table (1953). This was his penultimate film. The appropriately-named Adrian Spies (Dark of the Sun, 1968) wrote the screenplay based on the Victor Canning thriller. Making his movie debut was composer Dave Grusin (Divorce American Style, 1967)

Albeit made on a budget of just $900,000, MGM intended the picture for theatrical release but with a short cinema window to make it available for a speedy showing on ABC TV. It was originally scheduled for a May 1967 theatrical release but MGM, contractually obliged to deliver the picture within a specified time to television, could not fit in an American release. So it made its debut in the “Sunday Night at the Movies” slot on February 19, 1967, and was shown in cinemas abroad. Nor was it shown first on U.S. television because the studio believed it to be a disaster. Reviews were positive. Variety (February 22, 1967, page 42) called it “very hip.”