Truth was the first casualty. Matthew Hopkins, the character played in the film by Vincent Price, was 27 when he died in 1647. He had been hunting witches for three years. Price was 57 when the movie appeared. Co-star Ian Ogilvy, aged 25, would have been a better fit, though he lacked the menace. Oliver Reed, who had the swagger and the scowl, would have been the ideal candidate, age-wise, since he was just turning 30. And the movie might well have benefitted from presenting Hopkins as a young grifter who through force of personality and cunning held a country to ransom.

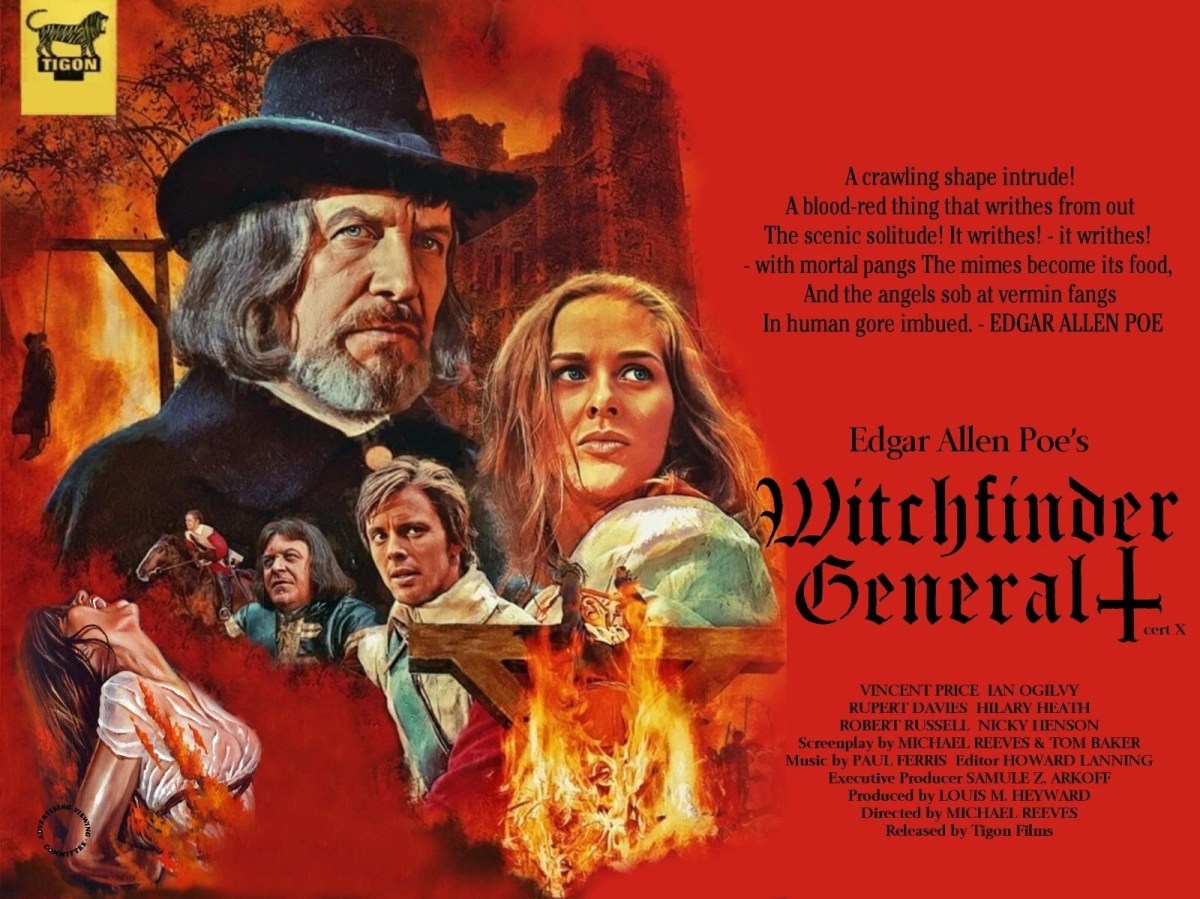

Price wasn’t director Michael Reeves’ (The Sorcerers, 1967) first choice. In fact, he originally wanted buddy Ogilvy, who had played opposite Boris Karloff in The Sorcerers. When that idea failed to float with Tony Tenser – previously head of Compton Films – now boss of British horror outfit Tigon, a challenger to the Hammer crown, Reeves pivoted to Donald Pleasance who, although better known as a supporting actor in the likes of The Great Escape (1963), had headlined Roman Polanski’s chiller Cul de Sac (1966). But when Tenser did a deal with American International Pictures, the U.S. mini-studio insisted on contract player Vincent Price, the mainstay of their Edgar Allan Poe output, with 16 previous films (out of 74) for the company.

Twenty-one-year-old Hilary Dwyer (The Oblong Box, 1969), under contract to Tigon, made her movie debut. Rupert Davies (The Oblong Box) was a seasoned veteran while Nicky Henson (Here We Go Round the Mulberry Bush, 1967) was a potential breakout star.

Tigon was a relatively new entrant to the horror scene, founded in 1966 by Tenser. Its second picture was The Sorcerers; this would be its fourth. Tenser has bought, pre-publication, the rights to Ronald Bassett’s novel Witchfinder General, published in 1966. Director Reeves faced something of a deadline once Tenser finalized the £83,000 budget. AIP chipped in £32,000 which included a £12,000 fee for Price. While it was Tigon’s biggest film to date, it was pin money for AIP.

The film needed to begin shooting by September 1967 at the latest to avoid the worst of the British cold weather. But the screenplay proved too unpleasant for the taste of the British censor. Reeves had already begun the screenplay with Tom Baker (The Sorcerers) with Donald Pleasance in mind portraying “a ridiculous authority figure” and had to quickly revamp it for Price. The laws of the period required a green light for the script from the British Board of Film Censors, who were repulsed by a “study in sadism” which dwelt too lovingly on “every detail of cruelty and suffering.”

That draft was submitted on August 4, 1967. The second draft, submitted on August 15, proved no more appealing. A third, substantially toned-down version, was approved. This resulted in the elimination of gruesome details of the Battle of Naseby and a change to the ending.

Production began on September 18, 1967. Star and director clashed. Reeves refused to go and meet Price on arrival at Heathrow Airport and told him, “I didn’t want you, and I still don’t want you, but I’m stuck with you.” The star was riled by the director’s inexperience. When told to fire a blank pistol while on horseback, Price was thrown from his horse after the animal reared up in shock at the sound. Price, in real-life a very cultured person, was surprised at Reeves’ attitude because in general he got on with directors.

Price turned up drunk on the last day of shooting, the filming of his character’s death scene. Reeves was planning revenge and told Ogilvy to really lay into the star. But the producer, anticipating trouble, ensured Price was well padded.

Reeves was better known for his technical rather than personal skills. Ogilvy commented: “Mike never directed the actors. He said he knew nothing about acting and preferred to leave it up to us.” That wouldn’t square with him falling out with Price over his interpretation of the character. And Hilary Dwyer saw another side of Reeves. “He was really inspiring to work with,” she said, “And because it was my first film, I didn’t know how lucky I was.” She would work with Price again on The Oblong Box and Cry of the Banshee (1970).

Tony Tenser, egged on by AIP’s head of European Productions, shot additional nude scenes in the pub sequence for the German version, A continuity error was responsible for the freeze-frame ending. There was a short strike when the production fell foul of union rules. Producer Philip Waddilove and his wife Susi were occasionally called upon to act.

Two aircraft hangars near Bury St Edmunds in Suffolk were converted for the interiors while a wide variety of locations were utilized for exteriors including Lavenham Square in Suffolk, the coast at Dunwich, also in Suffolk, Black Park in Buckinghamshire, Orford Castle in East Anglia, St John The Evangelist Church in Rushford, Norfolk, and Kentwell Hall in Long Melford on the Essex-Suffolk border. When the operation could not afford a camera crane, the crew improvised with a cherry picker.

Despite the tension on set, Price was pleased with his performance and the overall film. He praised the film in a 10-page letter. Price remarked, “I realized what he wanted was a low-key, very laid-back, menacing performance. He did get it but I was fighting him every inch of the way. Had I known what he wanted I would have cooperated.”

AIP retitled it The Conqueror Worm for U.S. release, hoping to snooker fans into thinking this fell into the Edgar Allan Poe canon, since the title referred to one of the author’s poems, part of which was recited over the credits.

The movie was generally lambasted by critics for its perceived sadistic approach, but is now considered cult. It was a big box office hit, especially considering the paltry budget, gaining a circuit release in the UK – “very good run beating par by a wide margin” – and despite being saddled with the tag of “unlikely box office prospects” by Variety did better than expected business in New York ($159,000 from 28 houses), Los Angeles (a “lusty” $97,000 from 16) and Detroit ($35,000 from one). The final U.S. rental tally was $1.5 million placing it ahead in the annual box office charts of such bigger-budgeted efforts as Villa Rides starring Yul Brynner and Robert Mitchum, Anzio with Mitchum again, James Stewart and Henry Fonda in Firecreek and Sean Connery and Brigitte Bardot in Shalako.

SOURCES: Benjamin Halligan, Michael Reeves (Manchester University Press) 2003; Lucy Chase Williams, The Complete Films of Vincent Price (Citadel Press, 1995); “Big Rental Films of 1968,” Variety, January 8, 1969, p15; Steve Biodrowski and David Del Valle, “Vincent Price, Horror’s Crown Prince,” Cinefantastique, Vol 19; Bill Kelley, “Filming Reeves Masterpiece Witchfinder General,” Cinefantastique, Vol 22; “Box Office Business,” Kine Weekly, June 1, 1968, p8; “Review,” Variety, May 15, 1968, p6. Box office figures – Variety, May-August 1968.