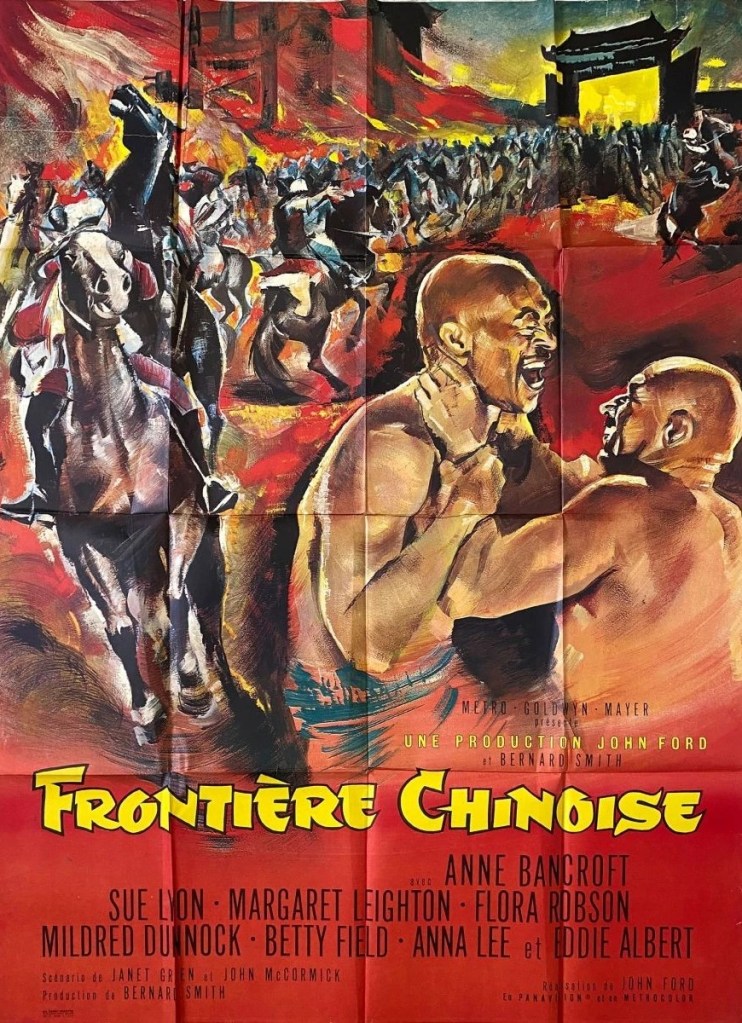

This is a very difficult review to write. John Ford has been one of my idols and to some extent when I first became interested in the movies I was force-fed the director, who was considered at the time to be a demi-god. While he has moved up and down in terms of critical acclaim, his westerns have stood the test of time, The Searchers (1956) still considered one of the best ever made and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962) fast challenging that dominance.

When he made westerns, he tended to be on safe ground. For other genres, acceptance was more fleeting. I can’t be the only one who was appalled by Gideon’s Day (1958) and found The Last Hurrah (1959) somewhat ho-hum and took Donovan’s Reef (1963) with a large pinch of salt. Even so, it’s with some regret that I have come to the conclusion that his final film, 7 Women, falls not just short of the high standards he set but is a poor picture.

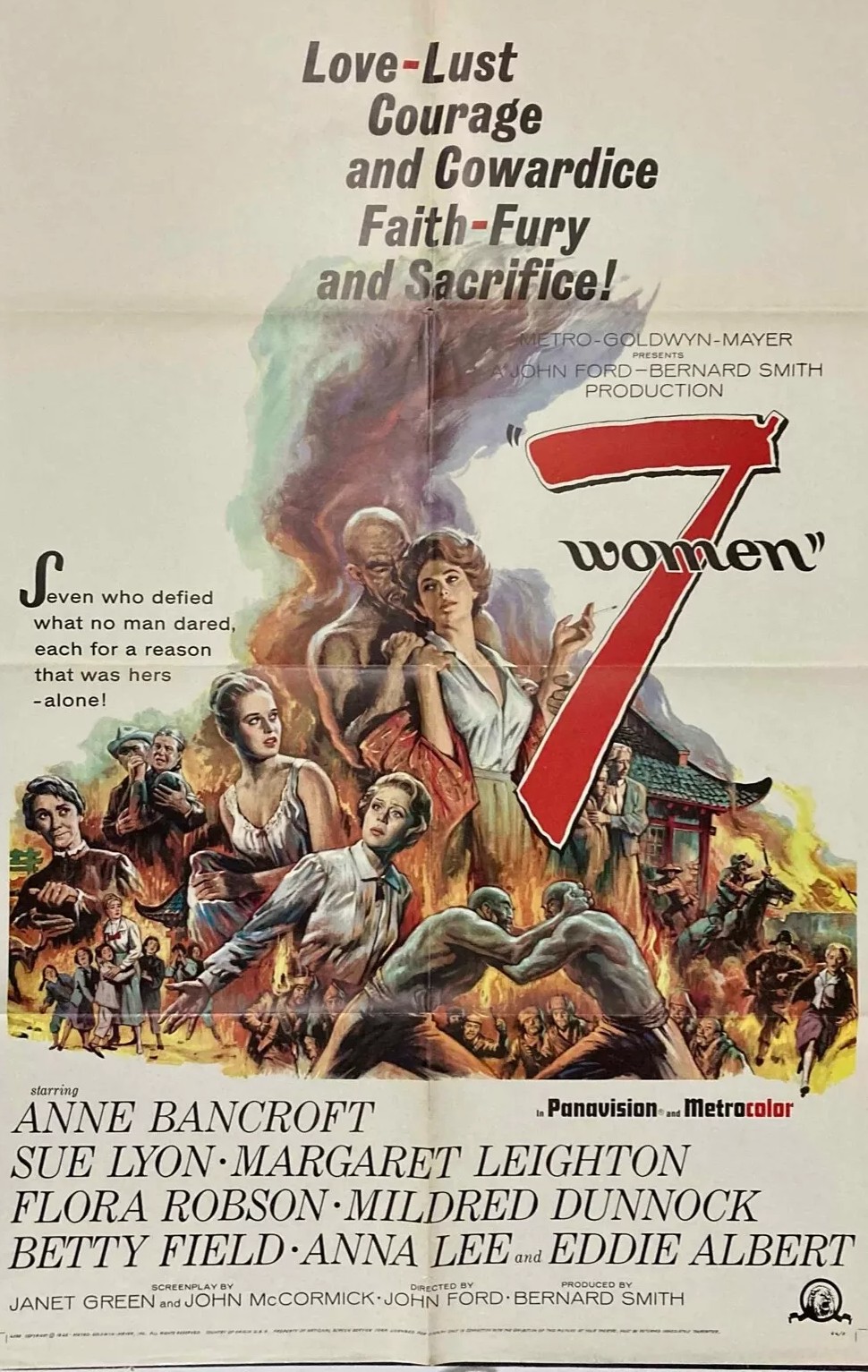

You have to wonder if he was still on the redemption streak that fueled Cheyenne Autumn (1964) and wanted to make amends for by and large reducing women to also-rans in his movies. There are some plus-points. It takes a rawer view of the Chinese missionary movie, this one set in 1935, not just the notion that Chinese rebels would not dare attack Americans but also that such establishments major on the pious and the gentle.

But in turn the constant bitching between the virtually all-female cast turns this into a glorified soap opera. There’s a constant battle between incoming heavy drinking free thinker Dr Cartwright (Anne Bancroft) and prim mission chief Agatha Andrews (Margaret Leighton) whose management style errs on the dictatorial. Cartwright is upbraided for smoking at dinner, bringing booze to the table, not standing for Grace, and worse of all, it would appear, having had sex. While there were further penalty points for taking a married man as her lover, it’s the mere notion of anyone having sex that sets off the over-pious Andrews.

Setting a new bar in the entitlement stakes is pregnant Florrie Pether (Betty Field) who’s coming very late to motherhood – she’s 42 – and was so determined to have a baby it was conceived with two months of marriage to ineffectual second husband Charles (Eddie Albert) and takes to the extreme the idea of pregnancy stimulating odd food needs – in the middle of nowhere in the middle of China she demands melon.

Added into the mix is that standard trope of the Chinese missionary picture, an outbreak of cholera. Mrs Pether can’t come to grips with the notion that the good doctor might have to concentrate on saving patients from plague rather than come running every time the pregnant gal feels the foetus kick.

So while Andrews and Cartwright are scoring points off each other, with the doctor further accused of corrupting the innocent young Emma Clark (Sue Lyon), outside pressures, introduced during the credit sequence but then left alone for way too long, grow. Chinese bandits are on the rampage. Another mission of a rival denomination led by Miss Binns (Flora Robson) turns up seeking refuge and eventually the bandits charge into the compound and demand ransom.

Naturally, such an invasion is going to get in the way of imminent birth, and while Andrews falls to pieces at the thought of sex producing an actual “brat”, it’s left to Cartwright to negotiate with the bandits. In return for cooperation, bandit chief Tunga (Mike Mazurki) demands sex with Cartwright. While such sacrifice only triggers further contempt and denunciation from Andrews, it does provide the other women with free passage out.

Cartwright, left behind, poisons the bandit chief and commits suicide.

There’s a heck of a lot of talk, which seems rather alien to Ford, who directs as if he’s fashioning a stage play rather than a movie, characters arranged almost in a series of tableaux. And the lighting and general atmosphere would have you believe you were watching a western rather than something set thousands of miles away.

Anne Bancroft (The Slender Thread, 1965) looks as if she’s strolled in from a western or a film noir with her tough talking stance and cigarette perpetually dangling and all those slugs from a bottle. Margaret Leighton (The Best Man, 1964) overplays the nervous breakdown and Betty Field (Coogan’s Bluff, 1968) is too often in a lather, as if they are in a hysteria competition. Sue Lyon (The Night of the Iguana, 1964) isn’t given enough to do. The other women, since we’re counting, include a more self-aware Flora Robson (Young Cassidy, 1965), Mildred Dunnock (Sweet Bird of Youth, 1962) and Anna Lee (In Like Flint, 1967). Written by the team of Janet Green and John McCormick (Victim, 1961) from the Norah Lofts short story.

Given John Ford went to extremes to place the Native Americans who had so often played the bad guys in his movies in a better light in Cheyenne Autumn, it seems odd he has reverted to instinctive racism here. There’s no suggestion that the bandits might be trying to win their freedom and they are often referred to as degenerate and by that awful epithet regarding their supposed color of “yellow.”

And it’s about time that revisionism was applied to the notion that Christianity had any right to be invading a country that had its own long-established traditions of religion and worship.

Has more of the feel of a Tennessee Williams text gone badly wrong than a John Ford number. Not the swansong the director deserved.