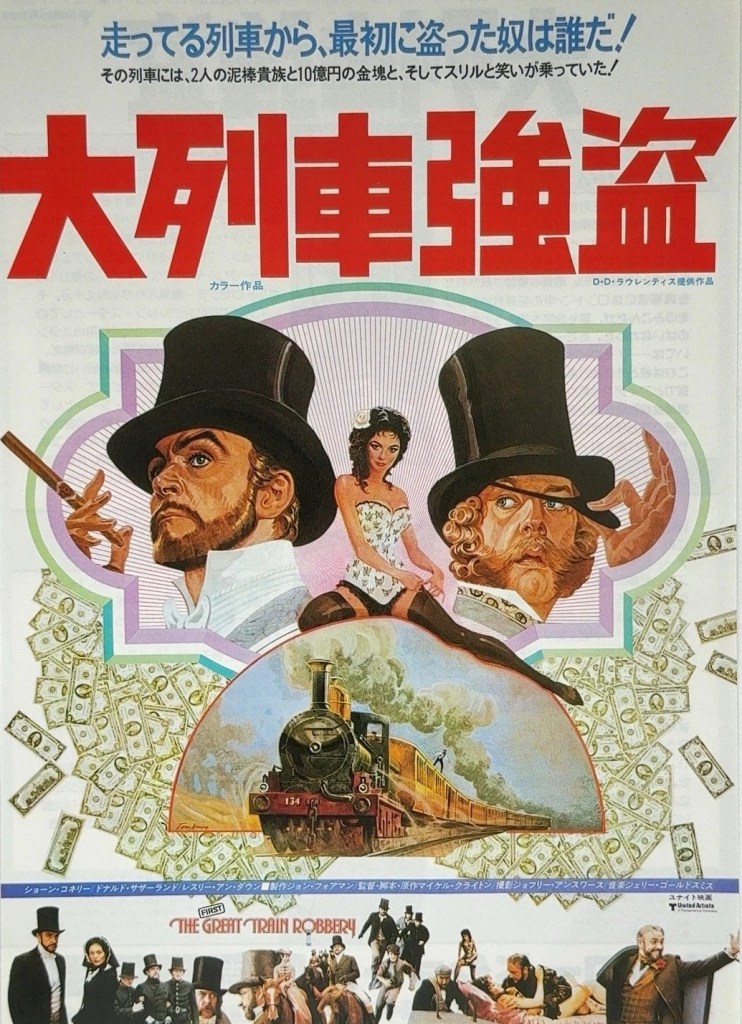

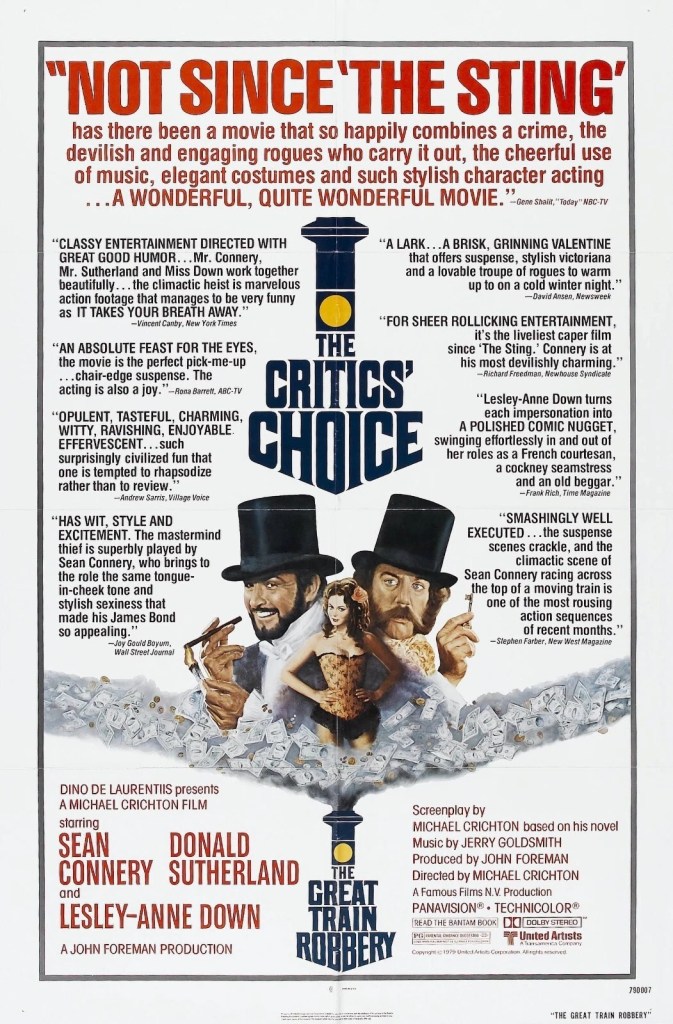

Back in the day your IP was the star. And here Sean Connery (The Hill, 1965) is the essence of that belief. The camera homes in on him. He steals every scene with an effortlessness that takes your breath away even as co-star Donald Sutherland (Don’t Look Now, 1973), complete with bizarre sideburns and winks to the audience, is huffing and puffing to compete.

Come at it as the standard heist movie and you will struggle to enjoy it because it is made up of too many different components. But approach it from a different perspective, that of The Sting (1973) as one critic suggests, and it takes on a different complexion and the getting there becomes a whole lot of fun. The background, Victorian England of the 1850s, doesn’t help so much as the sets look like they’ve been plundered from Oliver! (1968) and dirtied up a bit.

It’s worth remembering that in an era when the Mission Impossible series has been constantly sold on Tom Cruise undertaking his own stunts that Sean Connery did something much more dangerous than anything attempted by Cruise which was to race along the top of a train travelling at 55 miles an hour.

And if you need some contemporary analogy, look no further than the rich get richer and mostly through plundering. The ending presents the notion of a Robin Hood outwitting the forces of law and order to the acclaim of the public. But that would be to overlook the fact that chief thief Pierce (Sean Connery) is already so wealthy from previous nefarious dealings that he hobnobs with the rich, so accepted in their world of male clubs and high society that, like a financial trader, he is able to pick their pockets of vital information.

Though it’s not quite that easy. The target is a trainload of gold bullion heading for the Crimean War. And the two safes containing the dosh require four keys, each under the control of a different high-up official, requiring several separate audacious thefts. This involves some play-acting from the principals, dressing up in the main from female accomplice Miriam (Lesley Anne Down), clever duping by Pierce and old-fashioned burglary from pickpocket Agar (Donald Sutherland) who waves his fingers around like a demented Fagin, and whose main job is make wax impressions of stolen keys.

So Pierce pretends to be the ardent wooer of the daughter of one of the key holders, and Miriam essays a prostitute to relieve a key holder of the precious possession he wears around his neck. But the other two keys require a more professional approach which involves first of all the springing from prison of cat burglar Clean Willy (Wayne Sleep) to break into the guarded railway premises in a time-dependent operation.

But the cops get wind of the plan and increase security on the train, including adding a new padlock to the outer door. “Find me a dead cat!”, while not quite in the league of “The name’s Bond, James Bond” might well count as one of the best lines ever uttered by Sean Connery.

Said deceased animal is brought in to supply the necessary stink for a corpse should the cops consider opening the casket containing Agar which is to travel on the train, providing the team with the necessary inside man. But Agar and Miriam as the weeping widow of the supposed dead man have very little to do compared to Pierce who has to climb on top of the train, racing along the speeding top, drop down the side in an improvised harness and pick the padlock, then do the whole thing in reverse.

I may be wrong, and I’m sure someone will correct me if I am, but if this wasn’t the first time running along the top of a moving train was employed in a movie it certainly set a new standard, especially in the willingness of the actor to carry out his own stunts.

Pretty much all that remains after that is the twists that see Pierce captured and then escape. You could pick a few holes in it if you wish. The fact that after Pierce swapping coats (the one that had lain beside a dead cat for hours and provided sufficient stink to convince the lawmen) with Agar, nobody noticed the smell seems unlikely. The same would apply to bank manager Fowler (Malcolm Terris) who fails to spot that the widow he shares a compartment with for the entire journey is the prostitute who duped him, though that prospect does increase the tension.

If you’re expecting a standard heist movie then this takes way too long to come to the boil, but if you go along with the conceit and enjoy the playing especially of Sean Connery and ignore the mugging of Donald Sutherland it is in the forefront of the best robbery pictures.

And it’s worth noting the little gems in Connery’s acting. There’s a scene where Lesley Anne Down is berating him for making her become a prostitute (implicit is her fear she might actually need to have sex with the client). He’s eating an orange. Ignoring her complaints as just part of the job, he offers her some of his fruit as if his main worry is being seen to be rude hogging the fruit to himself.

Connery proves exactly why you hire a star. He carries the picture. There’s a lightness to his overall performance, notwithstanding the few times he needs to take a tougher line, that makes the film a joy. Whereas Donald Sutherland is either too heavy-handed or overacting. This proved a breakthrough role for Lesley Anne Down (British television’s Upstairs, Downstairs, 1973-1975).

Director Michael Crichton (Westworld, 1973) cuts himself too much slack in the first half of the picture which could have been considerably tightened up but comes into his own with the tension and twists of the heist and he has the good sense to rely on Connery’s interpretation of Pierce. He also wrote the script based on his own novel, a fictionalization of the actual original robbery attempt.

There already had been an incredibly famous Great Train Robbery in Britain in 1963, hence the need to differentiate this from that by inserting the prefix “First” to the advertising in Britain.

Great fun and worth a watch.