The global release is a relatively recent phenomenon. Back in the 1960s nobody would dream of letting loose a film on 7,000 screens worldwide all at once. In those days release patterns were a moveable feast. You could guarantee that a big new movie would open on a scheduled date in first run in a major city like New York, London or Paris, but after that it was anybody’s guess how long it might take to arrive at your local neighbourhood cinema. Especially, if a movie was part of the roadshow equation, it could occupy one cinema for months, maybe even years, and as long as it was screening there could go no further afield.

But even I was astonished, once I dug around in the files, to see just how long it took a movie to shift from world premiere to turning up at the last booking stations on the route, those tiny cinemas that appeared to litter small-town America. Towns with populations under 2,000 could still support a cinema. And it fell to the exhibitor to ensure a movie did not outstay its welcome. In Britain, cinemas in the 1960s screened films six days a week (Sunday films were subject to different regulations and were often one-off showings of old horror pictures hired on a fixed rental basis). Films ran for six days or the week was split into two, one program running Mon-Wed, the other Thu-Sat, the latter being allocated the movies with the better box office prospects.

It seemed, from an objective perspective, a fairly straightforward system. But in Britain a cinema with a catchment area of just a couple of thousand people would have gone to the wall a good time previously. All cinemas, even independent ones, fitted into some kind of release pattern, and might get the fifth or sixth or seven run of a movie after its big city first appearance, but, excepting roadshow, once it had made that vital first appearance you could rest assured it would take no more than six months or so to travel down the pipeline.

That did not hold true for small-town America. In 1967, for example, a picture could 18 months or more to reach towns such as St Leonard (pop 1900) in New Brunswick; Pittsfield (pop 2300) in New Hampshire; New Town (pop 1200) and Washburn (pop 968) in North Dakota; Lansing (pop 1328) in Iowa; St Johnsbury (pop 6000) in Vermont; England (pop 2136) in Arkansas; Flomaton (pop 1480) in Alabama; Oshkosh (pop 1100) in Nebraska; Grace (pop 775) in Idaho and Miltonvale (pop 911) in Kansas.

Weeks here appeared to be divided into three: Sun-Mon (or Sun-Tues); Tues-Wed (or Tue-Thu); and Wed-Sat (or Thu-Sat or Fri-Sat); and possibly into four if the exhibitor reckoned he had a bunch of stiffs. Certainly, minimal population counted against a small town being favored with a release ahead of a larger town. In addition, this type of exhibitor might well hold back until the rental terms were lower.

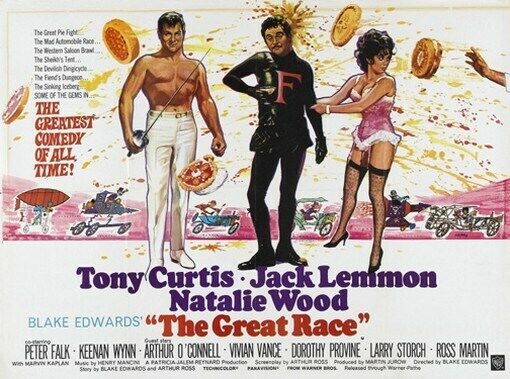

Tobruk was the fastest movie out of the blocks as far as these towns were concerned, just four months passed from its launch in February 1967 until showing up in one of these aforementioned towns. Murderers Row was not far behind, six months after its December 1966 release. But these were rarities. It took nearly two years for The Great Race, a roadshow release in1965, to gain a booking while The Sound of Music, another 1965 roadshow, was only available on condition it was hired for two weeks rather than the usual maximum four days.

And it was nine or ten months from first run to last run for Raquel Welch vehicle Fantastic Voyage, Jack Lemmon-Walter Matthau comedy The Fortune Cookie and Rock Hudson sci-fi Seconds. It took a full year for World War One epic The Blue Max, Cary Grant comedy Walk, Don’t Run and the Oscar-laden Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf to show. There was an even longer wait for Marlon Brando drama The Chase (sixteen months) and Sophia Loren starrer Judith (eighteen months).

Assuming that any movie showing on a Saturday was considered the best risk, the following films were perceived by exhibitors to offer the best prospects: Disney family comedy That Darn Cat (booked for two days), western spoof Cat Ballou (three), British spy picture Deadlier than the Male (three), William Holden Civil War western Alvarez Kelly (three), a revival of Hammer horror The Brides of Dracula (two), Lee Marvin-Burt Lancaster western The Professionals (three), Glenn Ford in Rage (three), British epic Khartoum (two), The War Wagon (four days in once cinema, only two in another), El Dorado (four days, running Fri-Mon), The Blue Max (four), Tobruk (two) and crime thriller Warning Shot (three).

Programs beginning on a Sunday I would reckon to have the next best chance of collaring an audience. Among these bookings were: The Great Race (three days), The Fortune Cookie (three), Fantastic Voyage (three), Paul Newman private eye thriller Harper (two), The Russians Are Coming, The Russians Are Coming (two), In Like Flint (two), Paul Newman western Hombre (two), Night of the Generals (three), Walk, Don’t Run (just one), The Quiller Memorandum (two), western remake Stagecoach (three) and Lost Command (two).

That sometimes left a two-day program in the middle of the week as a bonus in a good week or make-and-break in a bad one. Clearly, exhibitors took greater risks on pictures slotted in then. Sometimes the gamble paid off. Raquel Welch in Swingin’ Summer (two days), booked on the back of expectations for Fantastic Voyage, did surprisingly well. So did Wild Angels and a revival of Tom Jones.

Exhibitors were not slow in venting anger at a poor performer. Box Office magazine’s fortnightly feature “The Exhibitor Has His Say” – from which all this information is drawn – allowed the cinema owner to mouth off and warn fellow exhibitors. Terry Axley of the New Theatre in England was among the most vociferous. “Never been able to do much business on Ann-Margret,” was his view on Made in Paris. There was “no dice” for The Russians Are Coming, The Russians Are Coming. Despite Sean Connery, A Fine Madness did only “average business.” Fantastic Voyage “flopped here entirely.”

The Quiller Memorandum provided an all-time low for S.T. Jackson of the Jackson Theater in Flomaton. Walk, Don’t Run was a “real disappointment” at the Arcadia Theater in St Leonard. A Man Could Get Killed was pulled “after the poorest Sunday ever” at the Roxy in Washburn. Arabesque held “no appeal” for the audiences at the Scenic Theater in Pittsfield, where Stagecoach “didn’t seem to have much draw.”

But exhibitors were equally good at pointing to pictures that had exceeded expectations: Laurel and Hardy’s Laugh In, Born Free, Henry Fonda western A Big Hand for a Little Lady, Tony Curtis comedy Not with My Wife You Don’t, Dean Martin comedy western Texas Across the River, espionage spoof Bang! Bang! You’re Dead and a revival of Ma and Pa Kettle Back on the Farm from 1951.

What it showed was that one man’s turkey could prove another man’s golden goose. And while on the lowest rung of the distribution ladder that there was an inbuilt camaraderie that attempted to prevent fellow exhibitors from picking the wrong horse while hoping to pin their faith on an outsider romping home.

SOURCE: “The Exhibitor Has His Day,” Box Office, various issues, 1967.