Audiences weaned on glossy spies surrounded by pretty girls and generally their own country taking a straight moral path turned up their noses at this more realistic portrayal of the espionage business where dirty infighting was the stock in trade. The Spy Who Came in from the Cold (1965) was saintly by comparison.

Complaints about a complicated plot were led by critics who rarely had had to work their way through a tricky narrative, unless it was from the likes of Alfred Hitchcock who was apt to add twists to his stories. The fact that the bulk of the characters went by strange monikers – The Highwayman, Sweet Alice, The Warlock etc – also seemed to upset critics. (In the book by Noel Behn, the author points out that these spies were constantly adopting new identities, it made it easier for others to keep tabs on them if they were always referred to by nicknames which were constant.)

A contemporary audience, accustomed to things never being what they seem and all sorts of double-dealing, would be more at home here.

None of the characters, even the supposed good guys/gals, get off lightly. Personal unsavory sacrifice is unavoidable. Charles Rone (Patrick O’Neal) and B.A. (Barbara Parkins), who have fallen in love with each other, both have to prostitute themselves for the cause. And when the going gets too tough, suicide is the only way out. There’s hefty financial reward for those who survive the mission, but the substantial pot will be split between the survivors and not the dependents of those who don’t come home.

At the crux of the story is recovering a letter which promises that the USA and Russia will conspire against China and destroy its atomic weaponry. Espionage expert The Highwayman (Dean Jagger) recruits a team to infiltrate Moscow consisting of Rone, burglar and safe cracker B.A., drug dealer The Whore (Nigel Green), Ward (Richard Boone) and ageing homosexual The Warlock (George Sanders) who is a dab hand at knitting.

More than a few have a dodgy past, Ward an art dealer of ill repute, The Whore a pimp, even Col Kosnov (Max von Sydow), the target of the US operation, betraying his own countrymen. B.A. has to learn how to use sex to trap the enemy and, to get past the starting gate, loses her virginity to the obliging Rone.

The Whore sets up in the brothel business with Madame Sophie (Lila Kedrova), keeping the sex workers docile by filling them up with heroin, which he imports. As instructed, B.A. shares out her favors with the enemy while Rone seduces the wife, Erika (Bibi Andersson), of Col Kosnov.

You always go into a spy picture expecting double cross and this is no different. B.A., The Whore and The Warlock have their covers blown, the latter committing suicide, the girl failing to do so but paralyzed as a result. Ward kills Kosnov. But his motive seems odd – blaming the Russian for betraying his countrymen – and his action only becomes clear at the climactic double cross when Ward is revealed as a double agent in the pay of the enemy. For which, it has to be said, he doesn’t suffer. If anything, with B.A. in his hands, he has Rone over a barrel.

While this was never going to be a by-the-book espionage number, it’s elevated by exploring the emotional price that has to be paid, both in hiding some feelings and feigning others.

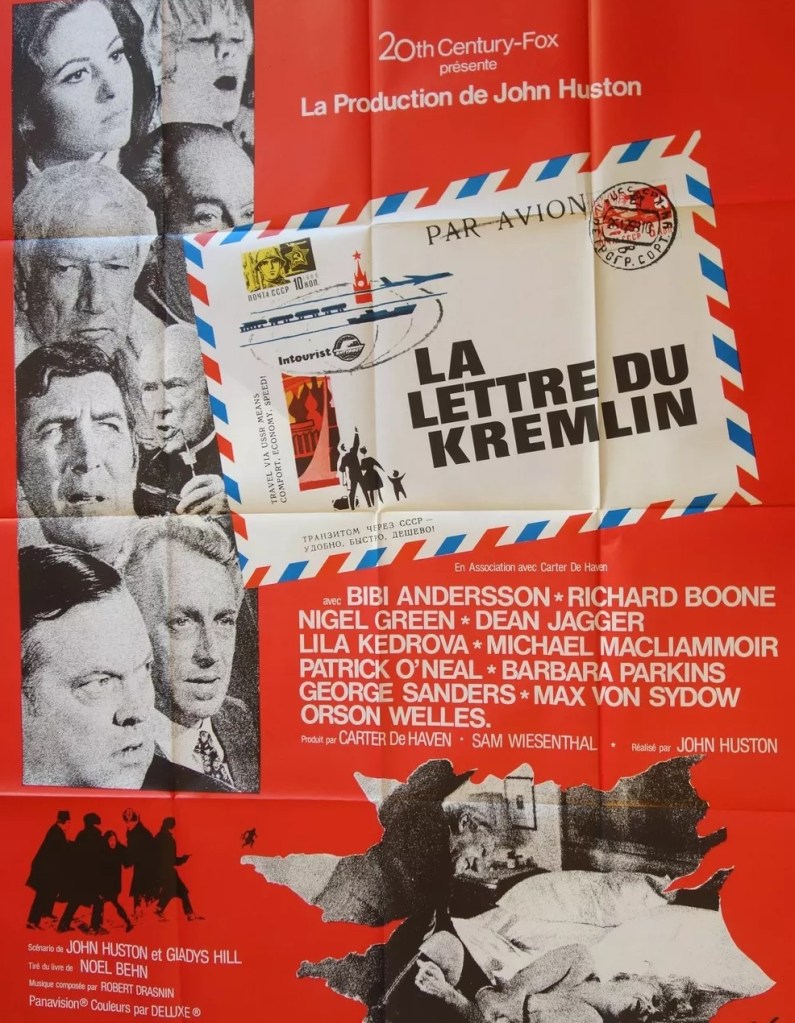

While possibly it made sense to present the stars in alphabetical order, suggesting nobody took precedence in the billing, most have the opportunity to play against type. Barbara Parkins (Valley of the Dolls, 1967) is excellent as the girl embarking on a career for which she has, emotionally, little aptitude. Bibi Andersson (Duel at Diablo, 1966), usually cast in repressed roles, has a ball as woman giving in to impulse. Tough guy Patrick O’Neal (Stiletto, 1969) must knowingly betray his true love. Richard Boone (The Night of the Following Day, 1969) is already playing a secret role and effortlessly dupes his colleagues.

There’s not much of the John Huston (Sinful Davey, 1969) visual magic but he makes up for that by allowing the actors to delve deeper into their characters. But he doesn’t attempt to spin a happy ending and the downbeat climax suggests that the USA lost this battle. The one memorable image is a ball of red wool rolling across the ground, indicating that The Warlock is dead. Written by Huston and Gladys Hill (The Man Who Would Be King, 1975) from the bestseller by Noel Behn (The Brink’s Job, 1978).

While the themes didn’t appeal then, they resound now.

Has aged very well.