While Hollywood was capable of dealing with mental illness head-on in pictures like Frank Perry’s David and Lisa (1962), Sam Fuller’s Shock Corridor (1963) and Robert Rossen’s Lilith (1964), the British were more inclined to take an alternative approach. The titular characters of Billy Liar (1963) and this film dealt with awkward reality by creating a fantasy world.

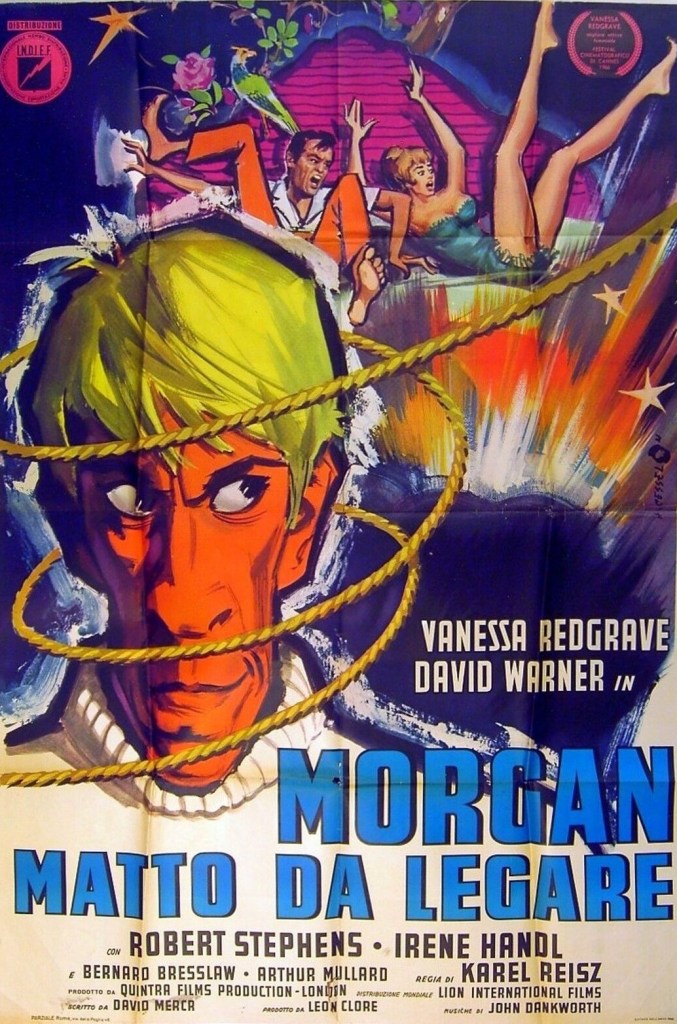

Morgan (David Warner in his first starring role), is a failed artist and virulent communist who cannot come to terms with being divorced by rich Leonie (Vanessa Redgrave) who is planning to marry businessman Napier (Robert Stephens). Morgan forces his way back into his wife’s house and attempts to win her back with nothing stronger than whimsicality and when that fails resorts to kidnap.

And it is clear that she shares his fancy for furry animals, responding to his chest-pounding gorilla impression with tiny pats of her own chest. For a slim guy, Morgan makes a believable stab at a gorilla, shoulders hunched up under his jacket, chest stuck out. And he has an animal’s sense of smell – detecting his rival’s hair oil.

The tone of the film is surreal. Had David Attenborough been a big name then you could have cited him as one of director Karel Reisz’s influences, such was his predilection for inserting wildlife into the proceedings, not just primates but giraffes, a hippo, a peacock and a variety of other creatures. Some are comments on Morgan’s state of mind but after a while it becomes monotonous. The film is clearly intentionally all over the place, the class struggle also taking central stage, but it’s hard work for the viewer. If you had stuck in some psychedelia, the fantasy would have made as much sense as The Trip (1967).

Having said that, towards the end of the picture there is an extraordinary image – possibly stolen from the opening of La Dolce Vita – of Morgan in a straitjacket hanging from a crane. Had that been the film’s starting point, it might have dealt more demonstrably with the subject matter. The whimsy is all very well but the focus on external animals does little to illuminate Morgan’s internal struggle and mental descent.

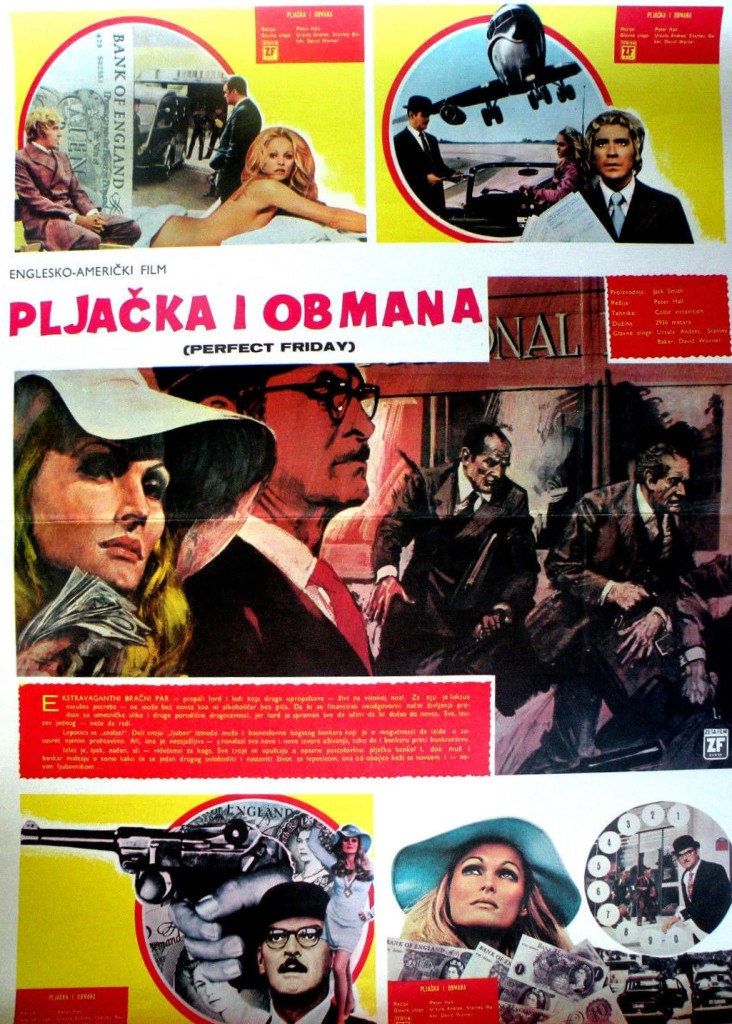

At this stage of his career, David Warner (Perfect Friday, 1970) exhibited a core instability, although later he was adept at ruthless villains. You could argue he is too charming for the role.

Vanessa Redgrave (Blow-Up, 1966), in her second film and her first starring role, steals the picture, winning her first Oscar nomination (in the same year as sister Lynn for Georgy Girl). She is made of gossamer. Still attracted to a man she knows will only bring her pain, she is far from your normal leading lady. There is a touch of the Audrey Hepburn in her ethereality but she portrays a completely genuine soul, not a manufactured screen personality. Robert Stephens (The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, 1969) adds a welcome hard core to the frivolity.

But Karel Reisz (Saturday Night and Sunday Morning, 1960) misses the spot. Distinguished British playwright David Mercer adapted his own BBC television work from 1962.

Could have done with taking a step back from the material and offered a more objective assessment.