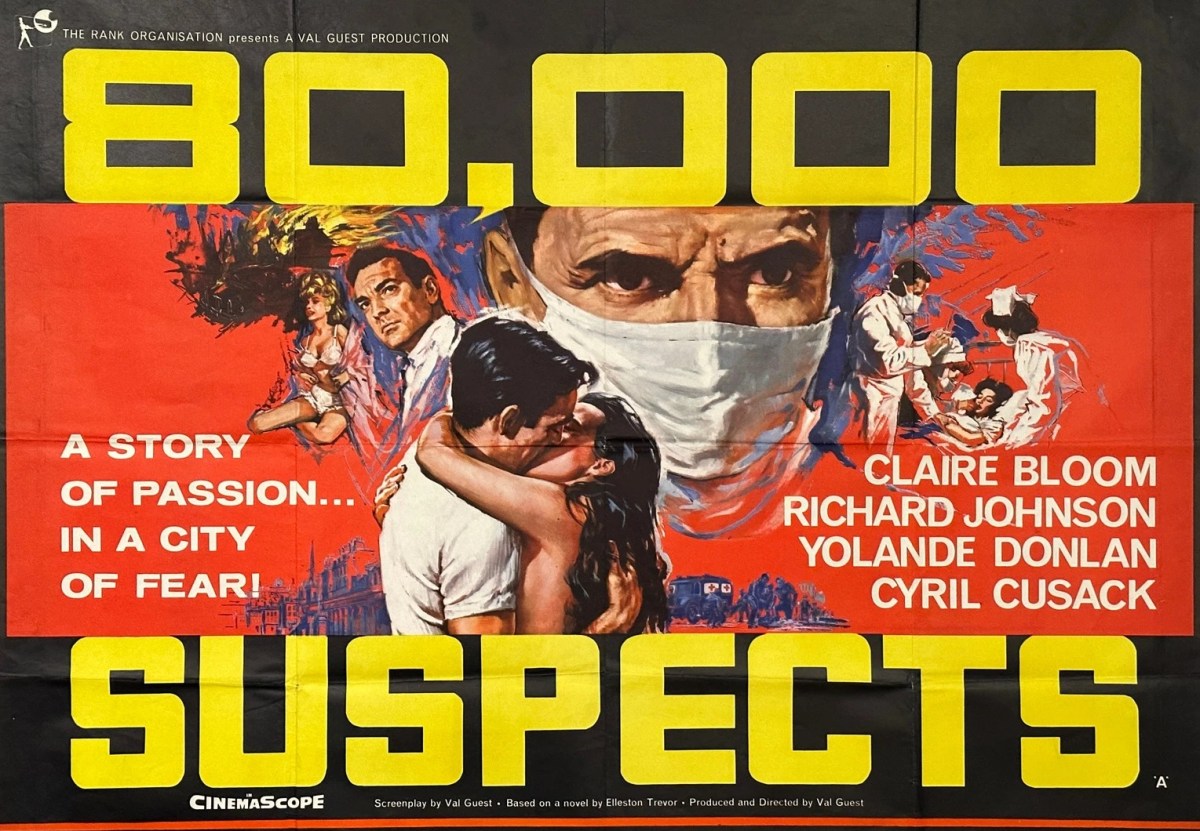

Eschews the X-cert terror of some of the end-of-the-world efforts of the period such as The Day the Earth Caught Fire (1961) and Day of the Triffids (1963) in favor of a more solid documentary-style approach and focusing on the tangled love lives of the main characters. There’s a distinctly British tone. People form long, orderly queues to receive an injection to combat a sudden epidemic of smallpox and police and any kind of hard-line enforcement plays a minor role. And the medical boffins in charge act more like detectives, tracking down potential infected individuals, engaging in door-to-door street-by-street hunts for those carrying the virus, maps are drawn, areas blocked off. There are deadlines and countdowns. Doctors are disinfected, clothes are incinerated and corpses cremated. So there’s enough tension to keep everyone on their toes.

But most of the emotional muscle is not by asking an audience to empathize or sympathize with those in danger or whose lives are suddenly cut short. But by concentrating on the impact of adultery on two couples. Dr Steven Monks (Richard Johnson), who identified the presence of smallpox in the large town of Bath with 80,000 people potentially at risk, is suspected by retired nurse wife Julie (Claire Bloom) of having an affair with glamorous Ruth (Yolande Donlan), wife to Monks’ stuffy colleague and friend Dr Clifford Preston (Michael Goodliffe).

The Monks are on the verge of going abroad on holiday when the smallpox disrupts their plans, although it’s Julie who appears the more principled and dutiful of the two, her husband being all set to head off and leave someone else to sort out the mess.

To make sure emotions are not sidelined by the scale of the epidemic, Dr Monks and wife are kept in the thick of it, the stakes rising dramatically when Ruth catches the disease. That triggers the most interesting – and original – sequence of the drama. When Steven thinks his wife is in danger of dying his feelings for her surge, but when she recovers, his ardor dampens down. He receives another kick in the teeth when he discovers that his lover Ruth has another fancy man.

So quite a lot of this is couples trying to work out their feelings, and it doesn’t follow the usual cliché, even though Julie is somewhat short-changed by the script in not being allowed to rage against her husband but passively accept his adultery. Dr Preston is more insightful, able to accept that his best friend has betrayed him, but sympathizing rather than condemning his wife because he knows that none of her adultery has brought her any happiness. It helps both of the Monks to have a wise padre (Cyril Cusack) available to listen to their troubles.

Though the epidemic is well drawn with plenty location work capturing the times, really the story is more about a pair of adventurous lovers, Steven and Ruth, landed with a pair of dullards in Ruth and Clifford, and making the necessary adjustments.

This was the first top-billed role of the career of British actress Claire Bloom (Three into Two Won’t Go, 1969) despite arriving on the scene in a blaze of leading lady glory. The Buccaneer (1958) opposite Yul Brynner and Look Back in Anger (1959) opposite Richard Burton should have been enough of a calling card, but she drifted to Germany and then television before another leading lady stint in The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm (1962) before tumbling down the credits for The Chapman Report (1962).

And except that she had outranked Richard Johnson in The Haunting (1963), you might wonder why she achieved top-billing here when Richard Johnson (Deadlier than the Male, 1967) has the bigger role. In theory, Bloom has the better role, she’s a victim of disease and has to cope with an unfaithful husband, but its Johnson who faces the bigger predicament in coming to terms with a love for Bloom that is at its peak only when he risks losing her.

High-spirited Yolande Donlan (Jigsaw, 1962) steals the early scenes. Decent support in Cyril Cusack (Day of the Jackal, 1973), Mervyn Johns (Day of the Triffids), Ray Barrett (The Reptile, 1966) and former big marquee attraction Kay Walsh (Oliver Twist, 1948).

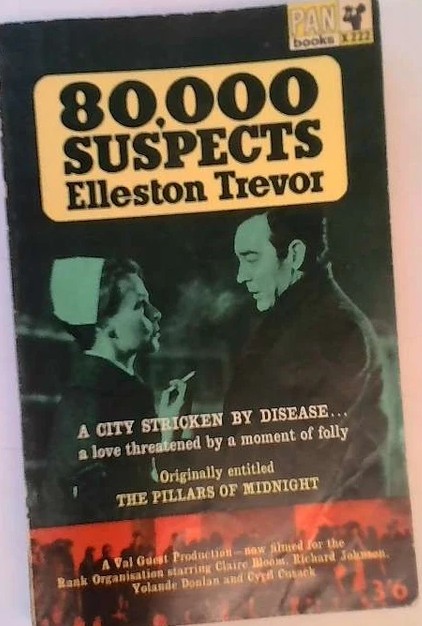

Val Guest (The Day the Earth Caught Fire) has to duck and weave with this one to ensure the human drama isn’t buried by the impending disaster – and vice-versa. Written by Guest based on the novel by Elleston Trevor (The Flight of the Phoenix, 1965).

An interesting watch.