You don’t realize the importance of treatment until you see an interesting story mangled. Taking the comedic approach to a heist picture is tricky. You can’t just make it happen because that’s what the script says, you’ve got to prove to an audience that whatever takes place is believeable. And frankly, asking three inexperienced dudes to smelt down a ton of gold and sneak it into a government building in the shape of a bust (the statue kind, not the other) and then smelt it back down again while inside and turn it into gold bars is a stretch too far.

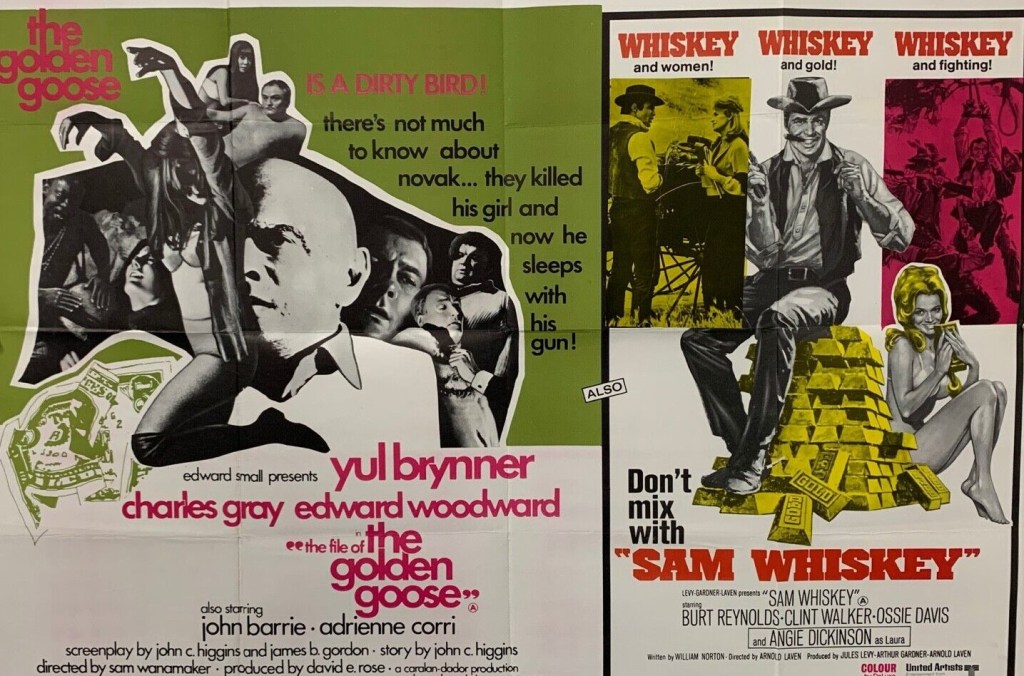

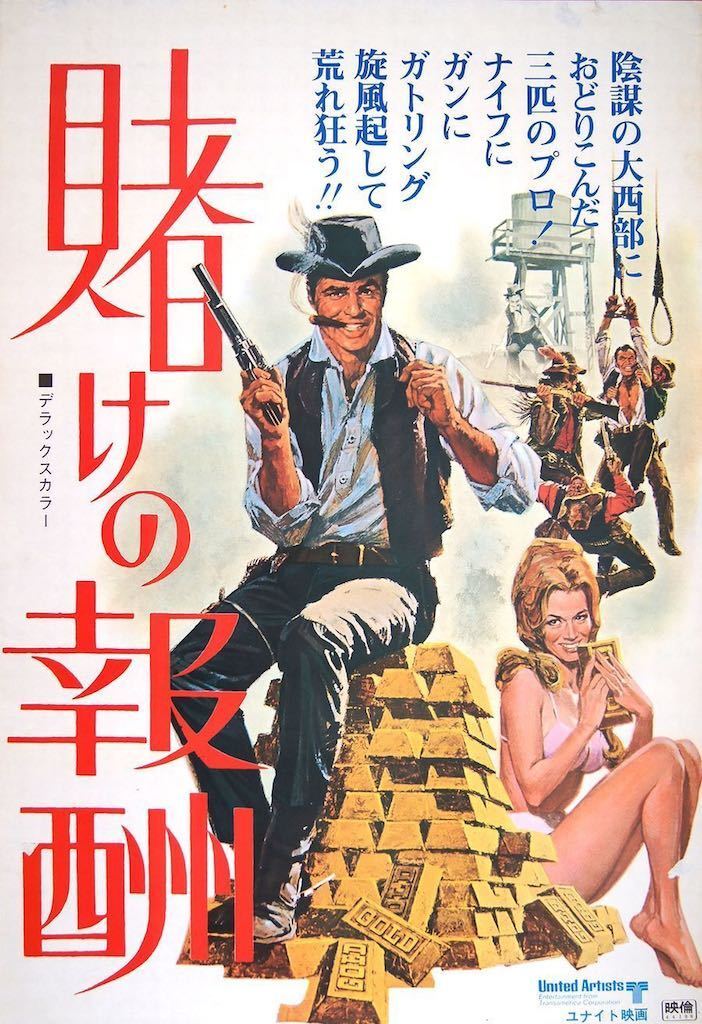

This is amiable enough as far as it goes, and Burt Reynolds gives his good-ol’-boy routine a try-out, Angie Dickinson strays from her usual screen persona, and it does present some interesting screen equality – a Yaqui Indian shown as someone you would pay a debt to, Ossie Davis making a pitch for the African American acting crown.

But it’s bogged down in a cumbersome plot that I guess many in the audience, like me, would have been begging for a switcheroo at the end that made more sense for the genre.

So, bear with me, Laura (Angie Dickinson) hires ex-gambler Sam Whiskey (Burt Reynolds) to retrieve $250,000 worth of gold ingots lying inside a sunken riverboat at the bottom of a river. Fair enough, you think, it’s the nineteenth century, nobody would be able to hold their breath that long to attempt to retrieve it even one gold bar at a time.

But she only wants the gold back to satisfy family honor. You see, her dead husband was in charge of transporting the gold to the local mint and to cover up his calmaity he replaced the gold with ingots made of lead. And hold on, there’s more, a Government inspector is due at the mint.

So, Sam and his buddies, blacksmith Jed (Ossie Davis) and strongman turned inventor O.W. Bandy (Clint Walker) have not just to recover the gold, and resist the temptation to simply spirit it away over the border, but find a method of getting it back inside the mint without anyone knowing and at the same time smuggle out the false ingots.

Of course, Laura has a blueprint of the plans of the mint so that’s okay then. And there’s a bust of her dead husband in the hallway of the mint and if Sam can just find the right excuse to take it away – and bearing in mind he has no obvious mold to use to re-cast it – he can re-make it in gold, return it, sneak it down into the smelting room and turn it back into gold bars.

Yes, the story is that complicated. Sam is only prevented from stealing the haul for himself by the seductive presence of Laura, who also has to act femme fatale enough to waylay the real inspector, whose identity Sam steals. I was praying that Laura, who seemed to be too good to be true what with all that family honor, was actually playing Sam for a patsy and that what was being removed from the mint was the real gold and what was being substituted was the fake.

No such luck. And this might well have worked if it had been treated seriously, if Sam was a famous robber, and if the director hadn’t interrupted proceedings every few minutes with some woeful comedy music and littered it with non-sequiturs or even provided a decent villain apart from Fat Henry (Rick Davis) and his motley crew who suspect something is up and attempt to hijack the gold before it reaches the mint.

And it’s a shame because the leading players are all an interesting watch. Burt Reynolds (Fade In, 1968), still a few years short of stardom, takes a risk in playing his character in light comedy fashion, coming off second best in his opening encounter with Jed. Angie Dickinson (Jessica, 1962) is far too genteel to play the femme fatale and it’s clear she only goes down the seduction route when Sam balks at the barminess of the idea, but it’s equally clear she’s the brains of the operation, and that’s pretty much a first in the western robbing business, and her character is so deftly acted that it’s only later, when you add everything up, you realize the depths of the character and that’s she only allowed audiences a glimpse of the surface.

Ossie Davis (The Scalphunters, 1968) doesn’t attempt the obvious either. He’s not after the Jim Brown action crown. He can look after himself with his fists, but he’s got the intelligence to avoid getting trapped by violence. And Clint Walker (The Great Bank Robbery, 1969), also primarily playing against type, is a muscular version of the crackpot inventor you usually found in a British comedy, but who is capable of coming up with an early version of diving equipment. And he has a great line that despite endless rehearsal he muffs up, “Aha!” he proclaims, battering in a bedroom door, in best Victorian melodrama fashion, “I caught you trifling with my wife.”

So it’s worth it for the performances and if you ever hankered after the seminal shot of a squirrel overhearing a conversation or wondered how many shots in one movie a director could contrive to make through a small space then this is for you. Screenwiter William Norton (The Scalphunters) had better luck with other directors but here Arnold Laven (Rough Night in Jericho, 1967) takes a wrong turning. Amiable is not enough, certainly not for a complicated heist picture.

Angie Dickinson and Burt Reynolds completists, though, will not want to miss this.