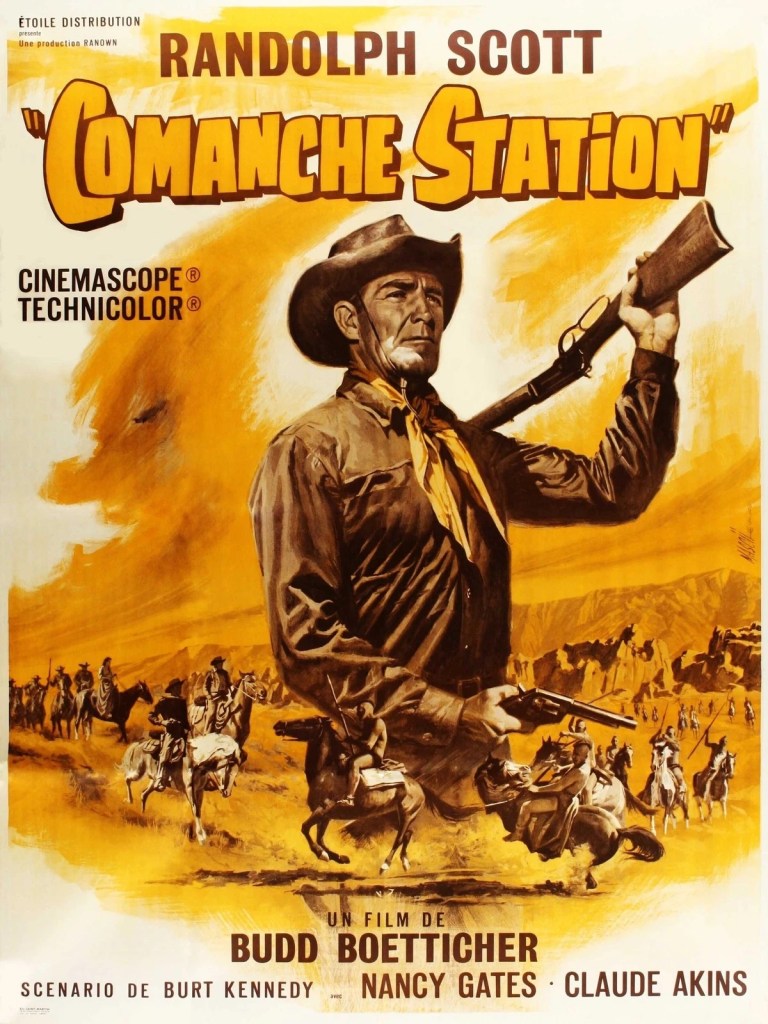

Randolph Scott went out on a high – or at least that was the plan, his intended retirement derailed when Sam Peckinpah made him an offer he couldn’t refuse for Ride the High Country / Guns in the Afternoon (1962). But if this was his planned final movie, he couldn’t have wished for a better last hurrah.

Director Budd Boetticher (A Time for Dying, 1969) became something of a cult item once the fashionista critics of the 1960s and 1970s got their hands on him, and pulled out the stops for low-budget pictures made with tight artistic vision in preference to an overload of bloated big budget efforts. This was the last of a western quintet starring Scott.

Boetticher exercises remarkable restraint throughout, very little in the way of emotion, or close-ups, and his use of widescreen follows the classic composition, relevant movement taking place to the side of the screen or in a corner or instead of left to right the action snakes top to bottom.

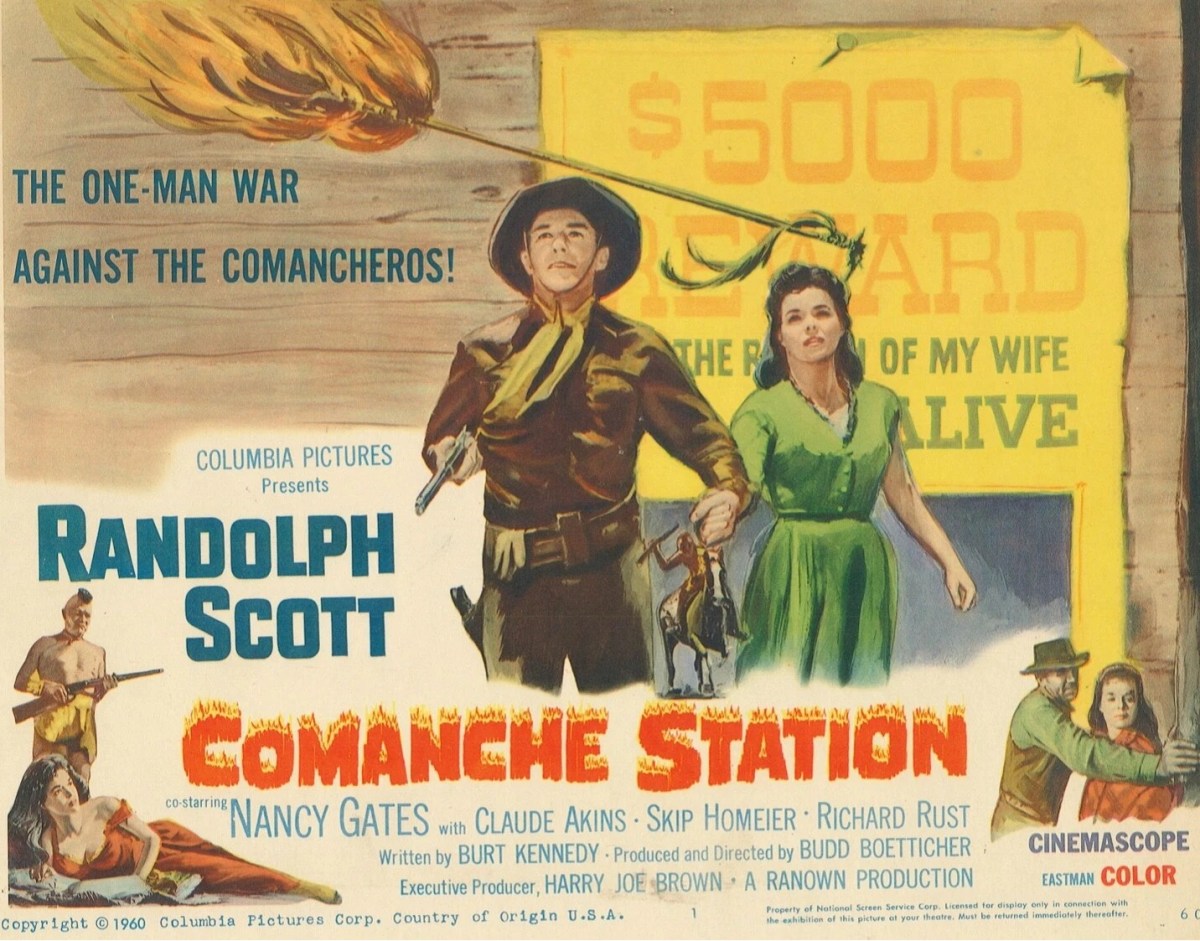

The story is exceptionally lean but in that simplicity carries enormous power. A man of principle Jefferson Cody (Randolph Scott) is up against the unscrupulous Ben Lane (Claude Akins), the situation complicated by the fact that the good guy isn’t going to make it out of Indian Territory without the help of the bad guy. At stake is a cool $5,000 (worth $125,000) today. Or put another way, a young woman’s life. There’s bad blood between Cody and Lane, the former court-martialing the latter while in the Army.

Cody has rescued kidnapped rancher’s wife Nancy (Nancy Gates), not by raiding the Comanche camp and pulling off the kind of action that used to take a well-practised team of experts (see The Professionals, 1966), but by hoving into view and offering to trade various goods, including a rifle, for the woman. She’s not as grateful as you might expect, fearing the reaction of her husband on her return (it’s unspoken but she would have been raped by her captors) and subsequent public humiliation.

When Comanches reappear, it looks like they’ve reneged on their deal. But they’ve not. They’ve been baited by Lane and his accomplices who, seeking the reward money, have gone in all guns blazing. Nancy turns against Cody because she imagines he, too, was after her for the money and not out of the goodness of his heart.

Lane fuels the fire by casting doubts on her husband not coming after her on his own, and pointing out that women thus rescued often rewarded their rescuer with sexual favors. Lane and his two younger buddies, Frank (Skip Homeier) and Dobie (Richard Rust), briefly discuss robbing Cody once he’s been handed the reward. But Lane has a better idea. Kill them both. The husband wants his wife back dead or alive.

Lane has the sense not to perve on the woman and the director resists the opportunity to pander to the audience by showing Nancy bathing naked in a river. Outside of the gunplay, the three outstanding scenes are smaller potatoes. One of the young lads proves he can read much to the amazement of his friend. When Frank is killed by an arrow he’s left to float down the river because nobody can afford the time to give him a proper burial. And when under attack, Cody dumps Nancy in a water trough to keep her hidden, from which she occasionally pops up sodden only to dive down again.

It’s pretty unusual for western to end on the kind of twist you’d find in film noir or a thriller. But this one is terrific. All the way through Nancy’s husband has been derided for not coming after her in person, but in the last scene we discover why. Her husband is, in fact, blind. Cody, who hasn’t been in it for the money anyway, turns away without taking a cent.

The running time is so lean – just 73 minutes – it would have been released as a supporting feature and it’s testament to the director’s principles that he didn’t try to puff out the length by sticking in some sub plots or encouraging romance.

Beautifully filmed and with a compact script by future director Burt Kennedy (The War Wagon, 1967). This was also the swansong for Nancy Gates. Claude Akins was cast by Kennedy for Return of the Seven (1966). Skip Homeier was the male lead in one of my low-budget faves Stark Fear (1962).

Compelling work and worth reassessment if you’ve not already climbed aboard the Boetticher/Scott bandwagon.