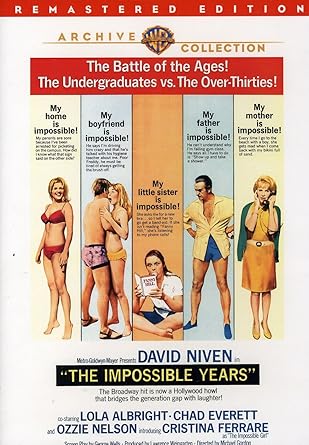

In the 1950s new talent was largely bloodied via small parts in big movies. In the 1960s, the easier route was to first build them up as television stars. This picture represents the nadir of that plan – female roles filled with established talent, males roles with actors who had made their names in television. And, boy, does it show, to the overall detriment of the picture.

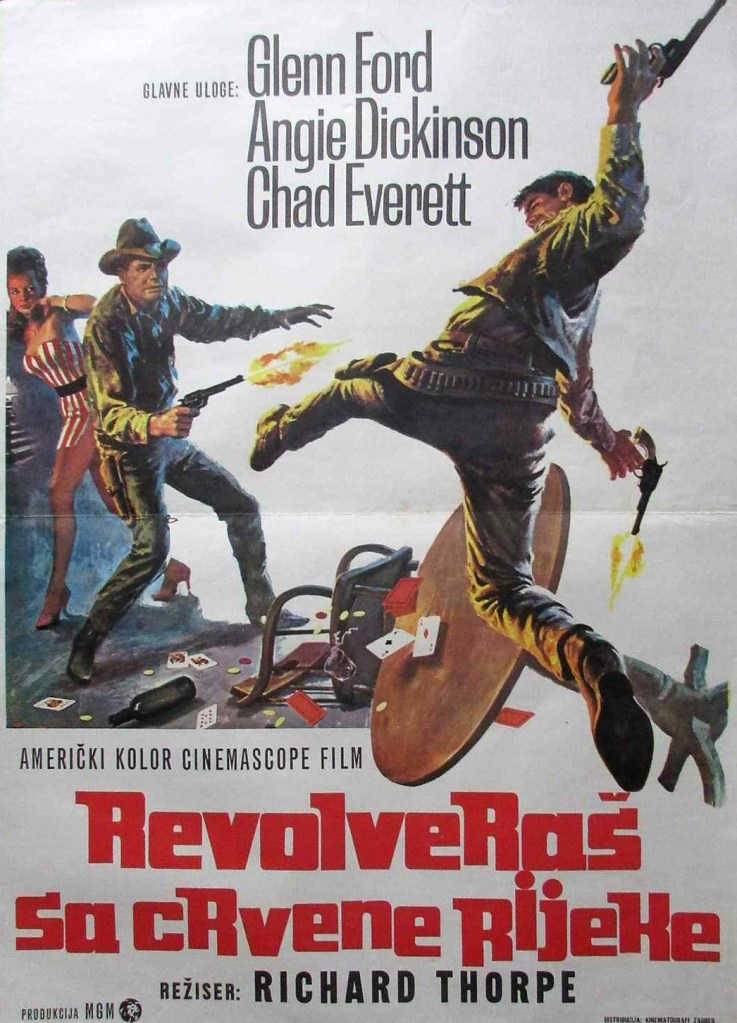

Warner Bros even had the temerity to top-bill Efrem Zimbalist Jr (hauled in from 77 Sunset Strip, 1958-1964) over more famous actresses. Zimbalist Jr at least had some marquee value after starring in low-budget A Fever in the Blood (1961) and second male lead in the classier By Love Possessed (1961) and Ray Danton (The Alaskans, 1959-1960) had played the title role in B-picture The George Raft Story (1961), but Ty Hardin was unknown beyond Bronco (1958-1962) and Chad Everett drafted in from The Dakotas (1962-1963).

Little surprise, therefore, that director George Cukor (Justine, 1969) concentrated his efforts on the females in the cast. But it was curious to find Cukor taking on this sensationalist project based on the surveys of sexuality that had taken the country by storm. Had it been made by a less important studio than Warner Bros it would have been classed as exploitation.

The bestseller by Irving Wallace on which it was based was a take on the Kinsey Report a decade before and others of the species and, theoretically at least, opened up the dry material of the more scientific reports into how men and women behaved behind closed doors.

Amazing that this was passed by the Production Code since dialog and action are pretty ripe. Interviewed women are asked about “heavy petting” and how often they have sex and if they find the act gratifying. One interviewer crosses the line and has an affair; these days that would be viewed as taking advantage of a vulnerable woman. And there’s a gang rape.

Given the movie’s source Cukor takes the portmanteau approach, four women undergoing different experiences. The problem with this picture is that there’s little psychological exploration. Women are presented by their actions not by their thought patterns or by their treatment by their husband.

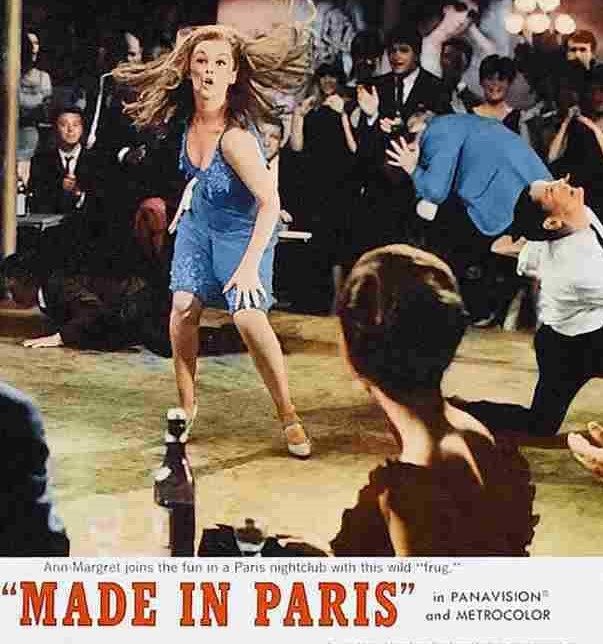

In what, in movie terms, is the standout section, Naomi (Claire Bloom), an alcoholic nymphomaniac, is so desperate for attention she throws herself at the delivery boy (Chad Everett), then at a married jazz musician (Corey Allen), with devastating effect, as he hands her over to his buddies, causing sufficient degradation that she commits suicide. Since we first come across her crying in bed, sure signs of depression, these days you would expect more exploration of her psychiatric state.

Similarly, the widowed Kathleen (Jane Fonda) has been tabbed frigid by her husband and nobody thinks to call into question his inadequacies as a sex partner rather than hers. Here it’s put down to daddy issues and growing up in a household heavy with morality.

Kathleen is taken aback by the researcher even asking her about sex, “physical love” the technical term, rather than a purer kind but her consternation at the questions being posed in very cold-hearted manner by an anonymous voice – researcher hidden behind a wall – does reveal how ill-equipped some people are to even talk about sex. Her story develops into some kind of happy ending, despite the fact that her interviewer Radford (Efrem Zimblist Jr) would be busted these days for taking advantage.

Teresa (Glynis Johns) is convinced by the interviewer’s tone that the simple normality of her own marriage must be abnormal and so, determined to fit in, embarks on a clumsy attempt to seduce footballer Ed (Ty Hardin), coming to her senses when it comes to the clinch.

The interview also has a major impact on the adulteress Sarah (Shelley Winters). After confessing her affair to husband Frank (Harold J. Stone) she rushes off to lover, theater director Fred (Ray Danton), only to find, to her astonishment, that he’s a married man. Her husband accepts her back.

To keep you straight, the “good” women are dressed in white, the “bad” ones in black. The filming is distinctly odd. The man behind the wall is filmed with no ostentation, but the style completely changes when the director turns to the women who often end up in floods of tears.

Claire Bloom (Two into Three Won’t Go, 1969) and Jane Fonda (Barbarella, 1968) are the standouts because they have the most emotion to play around with. Oscar-nominated Glynis Johns (The Cabinet of Caligari, 1962) is the comic turn. Over-eager over-confident Oscar-winner Shelley Winters (A House Is Not a Home, 1964) gets her come-uppance. None of the men make any impact.

The book took some knocking into shape. Perhaps because, of the four names on the credits only one had signal screenwriting experience, Don Mankiewicz (I Want to Live, 1958). For the others, better known for different occupations in the business, this was their only screenwriting credit. Wyatt Cooper was an actor married to Gloria Vanderbilt, Gene Allen art director on many Cukor pictures and production designer on this, and Grant Stuart was a boom operator though not on this picture.

Best viewed through a time capsule.