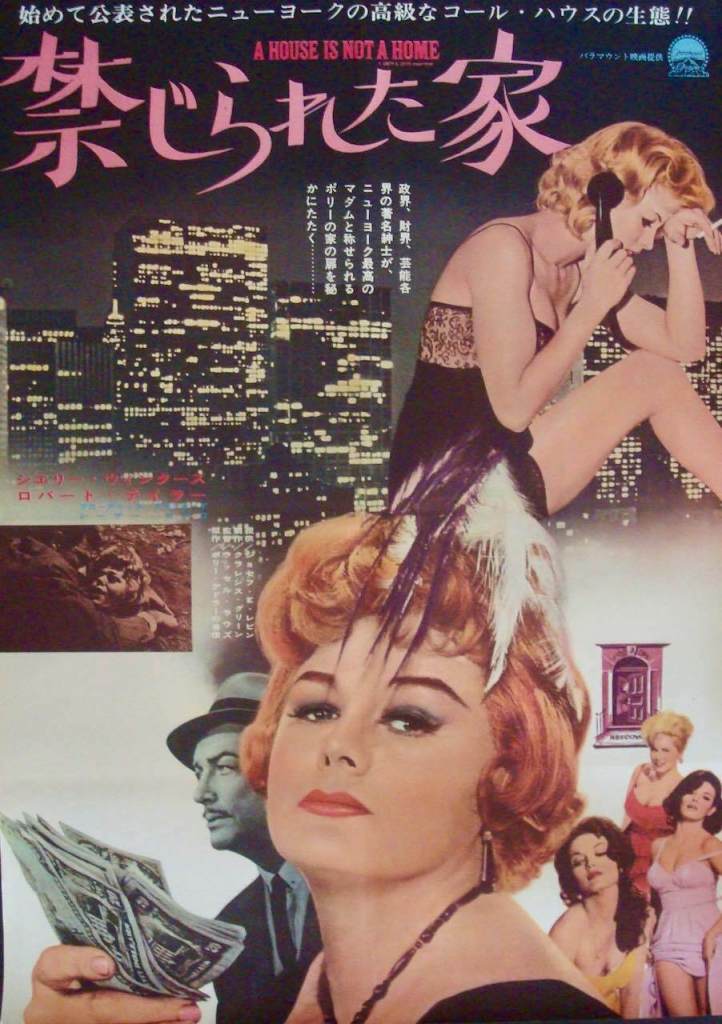

While perhaps best remembered these days as the debut film for Raquel Welch (One Million Years BC, 1966), the rest of the film is worth a look.

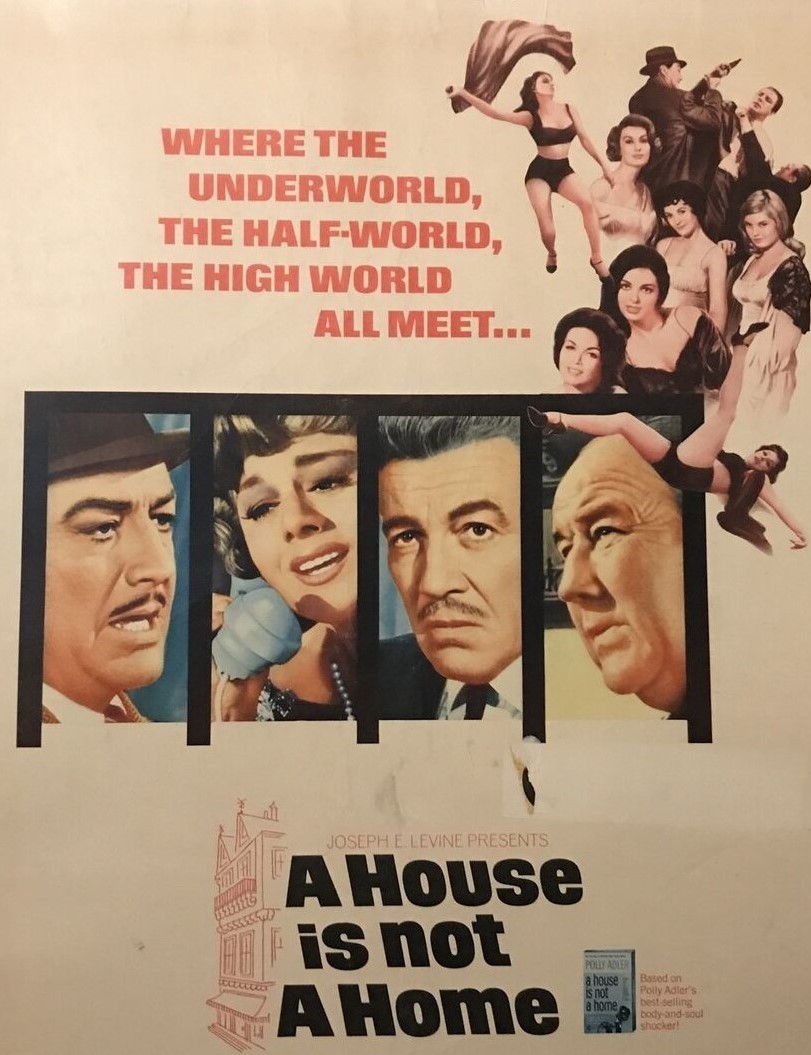

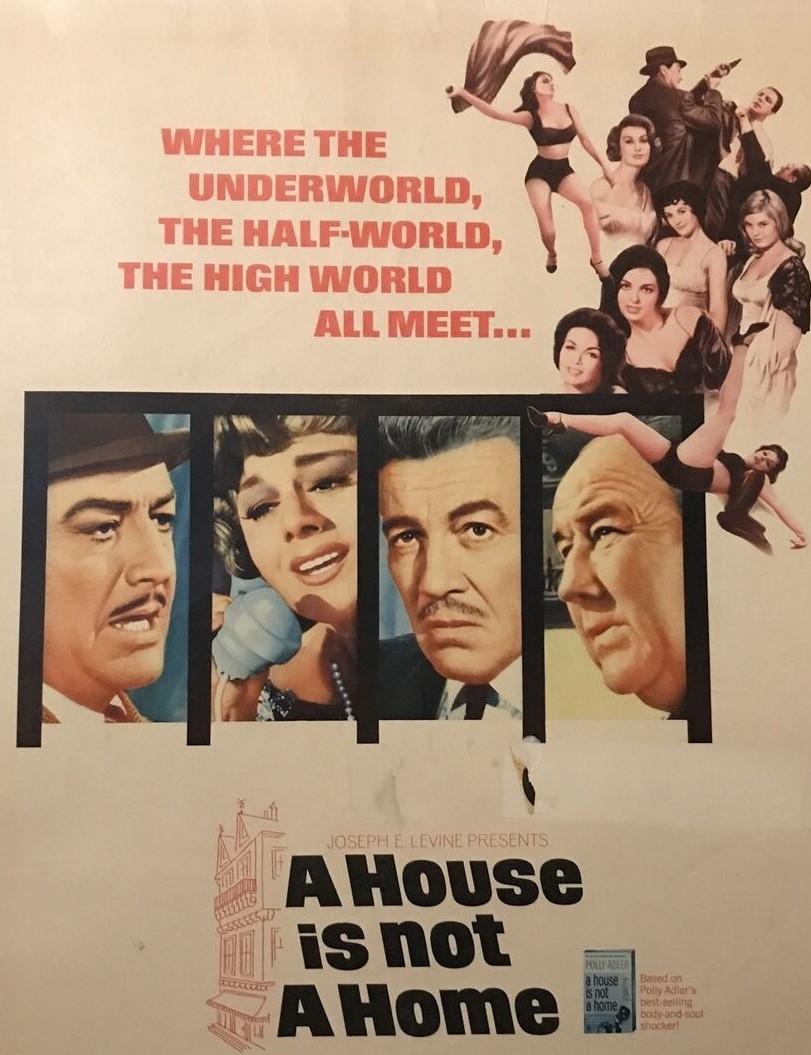

Hypocrisy had its heyday in The Roaring 20s when prohibition made bootleggers millionaires, helped bankroll other criminal activities like prostitution and encouraged cops and politicians to seek their share of the loot. The biography of real-life madam Polly Adler (Shelley Winters) covers all elements of corruption.

Thrown out of her own home after being raped, she finds a knight in shining armor in the shape of bootlegger Frank Costigan (Robert Taylor) and is soon, at first apparently innocently, pimping out her friends. The reality of what becomes her profession is not ignored, the word “whore” bandied around, with one girl, Madge (Lisa Seagram), turning junkie as a result, another, Lorraine, committing suicide. Like Go Naked in the World (1961) Polly realizes that true love has no place in her world, a relationship with musician Casey (Ralph Taeger) unsustainable.

Adler, in her many voice-overs, explains why vulnerable women become sex workers – poverty, lack of family and lack of hope is her take on it – and she professes to view it as a business and preferable to working in a factory for pitiful wages, but the movie is at its best in linking the nether worlds of infamy and showing that the woman is always the loser.

While any attempt to properly portray the period is hampered by lack of budget, it does provide an array of interesting and occasionally real-life characters, Lucky Luciano (Cesar Romero) for example. A brothel proves an ideal location meeting place for crooks and politicians, the latter easily bought by contributions to their campaign funds. Nor are cops shy about asking for donations to their Xmas funds, or using the facility.

The Adler operation puts a glossy shine on the shady business since all her girls are glamorous. But still the movie pulls no punches except in the case of the madam herself, presented too often as an innocent and as a person who never sold her own body and who saw nothing wrong in taking as much advantage of the vulnerable girls in her employ as the clients who paid for them.

Oscar-winner Shelley Winters (The Chapman Report, 1962), more often a supporting player at this point in the 1960s than the star, grabs the role with both hands and although unconvincing as the younger girl delivers a rounded performance minus the blowsy affectations that marred much of later work. One-time MGM golden boy Robert Taylor, pretty much in the 1960s reduced to television (The Detectives, 1959-1962) and low-budget pictures, shows a glimpse of old form as the smooth bootlegger.

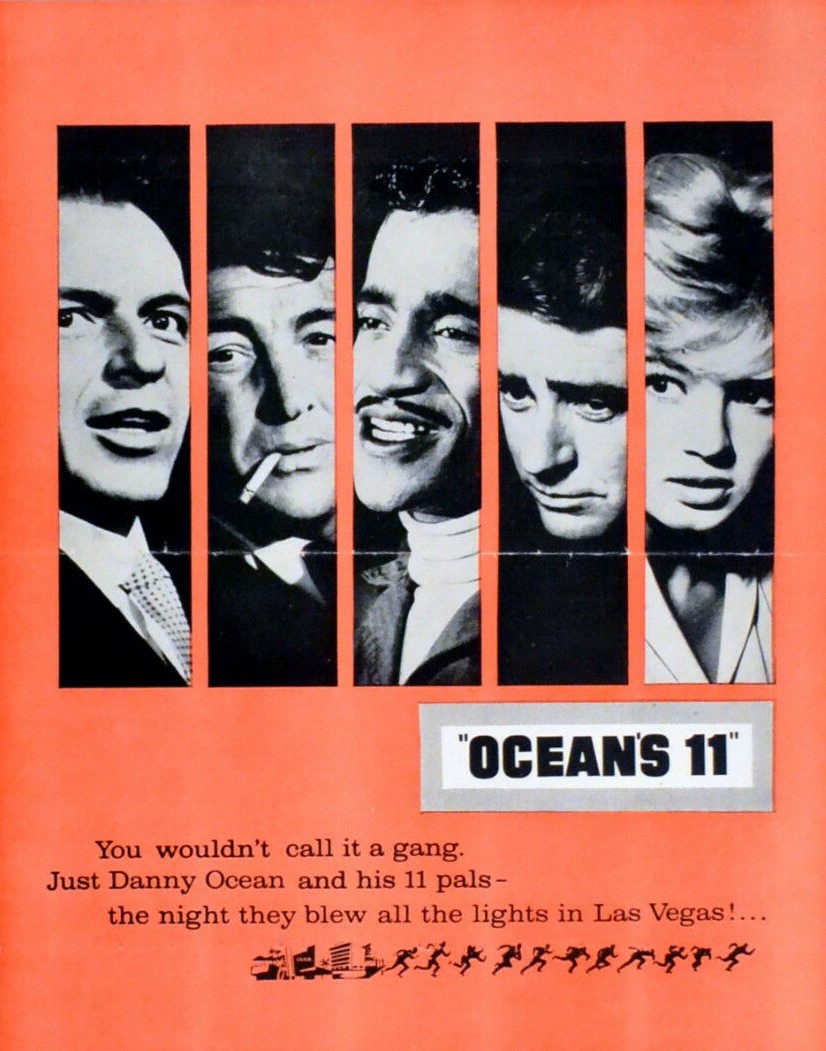

Cesar Romero (Oceans 11, 1960) and Oscar-winner Broderick Crawford (All the Kings Men, 1949) head up a checklist of old-timers filling out the supporting cast. Future director Lisa Seagram (Paradise Pictures, 1997) as the junkie hooker makes the biggest impact among the girls.

A flotilla of wannabes made up Polly’s girls. Apart from Raquel Welch, the only one to break into the big time was Edy Williams (Beyond the Valley of the Dolls, 1970). In the main they comprised beauty queens – Amede Chabot (Miss America), Danica d’Hondt (Miss Canada) and Leona Gage (Miss Universe) who had a small part in Tales of Terror (1962). Otherwise Sandra Grant became the most famous – for marrying singer Tony Bennett. Patricia Manning had the most screen experience, second-billed in The Hideous Sun Demon (1958), bit parts in television shows, and fourth-billed in The Grass Eater (1961). Inga Nielsen would later turn up as bikini fodder in The Silencers (1966), In Like Flint (1967) and The Ambushers (1967).

Director Russell Rouse (The Fastest Gun Alive, 1956) was better known for the screenplay of D.O.A. (1949) and had a story credit for Pillow Talk (1959). In fairness, although the film has no great depth, Rouse keeps it ticking along via multiple story strands although occasional lapses into comedy do not work. Written by Rouse and Clarence Greene (The Oscar, 1966) based on Adler’s autobiography.