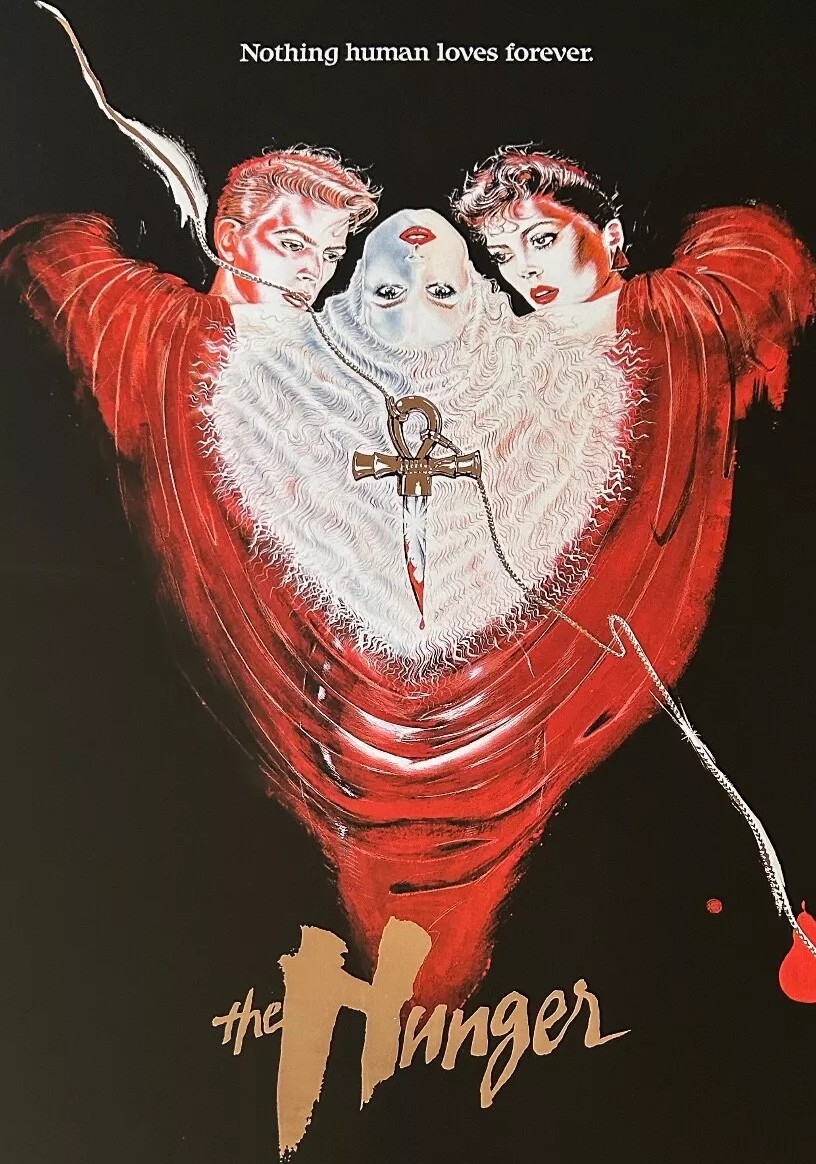

With this weekend’s Sinners claiming to reinvent the vampire picture, I thought it time to look back at a movie that genuinely did reimagine the vampire genre, though hardly acclaimed at the time.

Elegant, atmospheric, subtle. Never thought I’d be stringing those words together to describe an offering from uber-director Tony Scott (Top Gun, 1986). Add in “slow” and this is a director reinvented. Did I mention “short?” This clocks in just over the hour-and-a-half mark. So what might have driven an audience to distraction if stretched out over a languorous two hours twenty minutes, say, or longer, as would be par for the course in these more self-indulgent times, is not an issue.

If this has become a cult, it’ll be for all the wrong reasons. A vampire picture that doesn’t play by the rules, a lesbian vampire movie that steers clear of Hammer sexploitation, a lesbian movie featuring two top marquee names, or just any picture that features David Bowie.

There’s an inherent sadness to the whole exercise, an elegiac feel comparable to the likes of The Wild Bunch (1969). Miriam Blaylock (Catherine Deneuve) and husband John (David Bowie) are so stylish and have no truck with growing those oh-so-out-dated fangs that you are willing them to succeed especially as there’s no sign of a crucifix-wielding vampire hunter.

You might wonder why the cops haven’t been alerted to a spate of killings, throats cut in serial killer modus operandi fashion, but really there’s so much else going on – emotional, not action, you understand – that its absence isn’t worth commenting upon.

So first up is betrayal – and from a serial betrayer at that – as John realizes that while he has been promised eternal life by Miriam, who’s somewhere in the region of two millennia old, she can’t guarantee eternal beauty. So when he starts to suffer from ageing, cracks begin to show in their relationship. And whether he’s aware of this or not, she’s already lining up a replacement, the classical music student Alice (Beth Ehlers) they both tutor. And when John knocks her out of the equation, his pursuit of eternal youth or at least a reversal of the ageing process leads Miriam to a spare, scientist Sarah (Susan Sarandon).

The connection between the two women is initially so subtle that Sarah picks up the telephone imagining Miriam on the other end when the phone hasn’t even rung. Sarah is perturbed/excited to discover she has gay tendencies, especially when she’s already in a strong heterosexual relationship. And she’s not that keen, either, on discovering that she has been co-opted into the vampire fraternity.

Most of this has moved along in almost dreamy style so, that come the end, a sudden burst of twists takes you by surprise. You’ll find echoes to the priestess in Game of Thrones when the aged John seeks to kiss his lover. And John’s discovery at the end that’s he’s part of an undead harem carries over to the climax of Christopher Nolan’s The Prestige (2006).

Anyone looking for cheap kicks from the lesbian sex scene is going be disappointed, this is sex arthouse-style with wafting curtains getting in the way, and pleasure delivered in subtle rather than orgiastic fashion.

Tinged with a sense of loss, and pervaded by sadness, this is a complete outlier in the Tony Scott portfolio, especially the pace which is completely at odds with the fast-editing style for which he is best known. At the same time, tension remains high, in part because you don’t really know what Miriam is up to, and because these are new ground rules by which the vampires play, not least in their enjoyment of style and fashion, the kind of garb favored by the likes of Christopher Lee only employed as pretense and not by one of the main players.

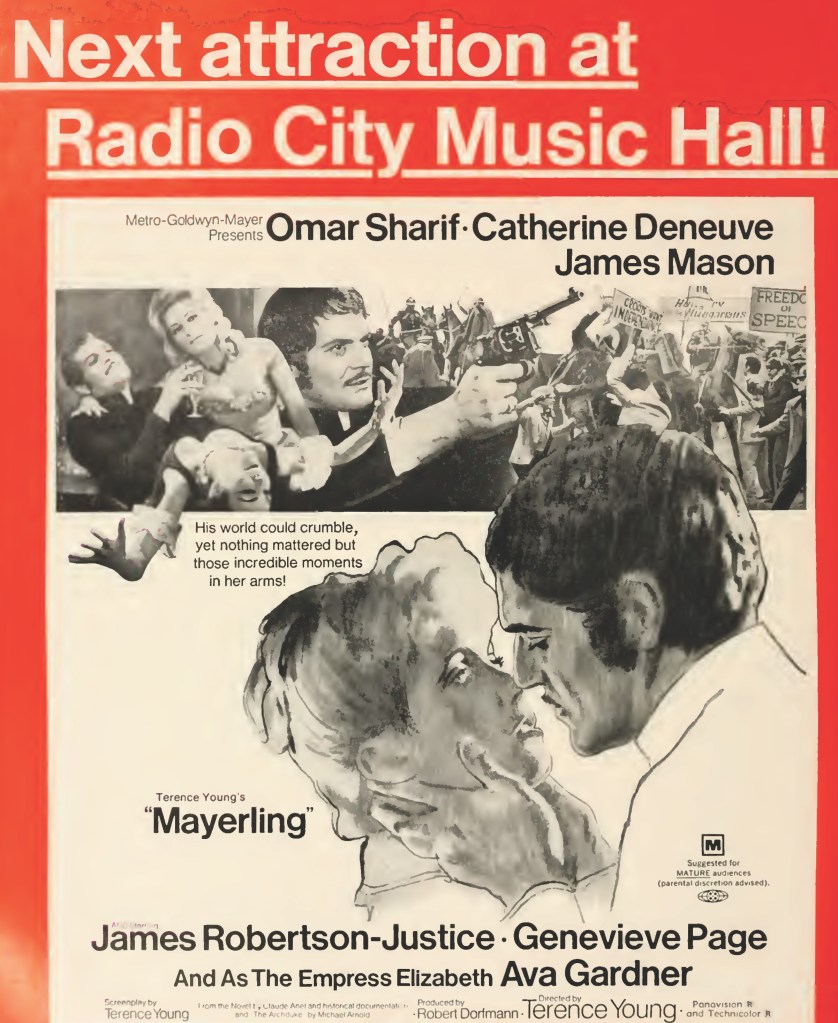

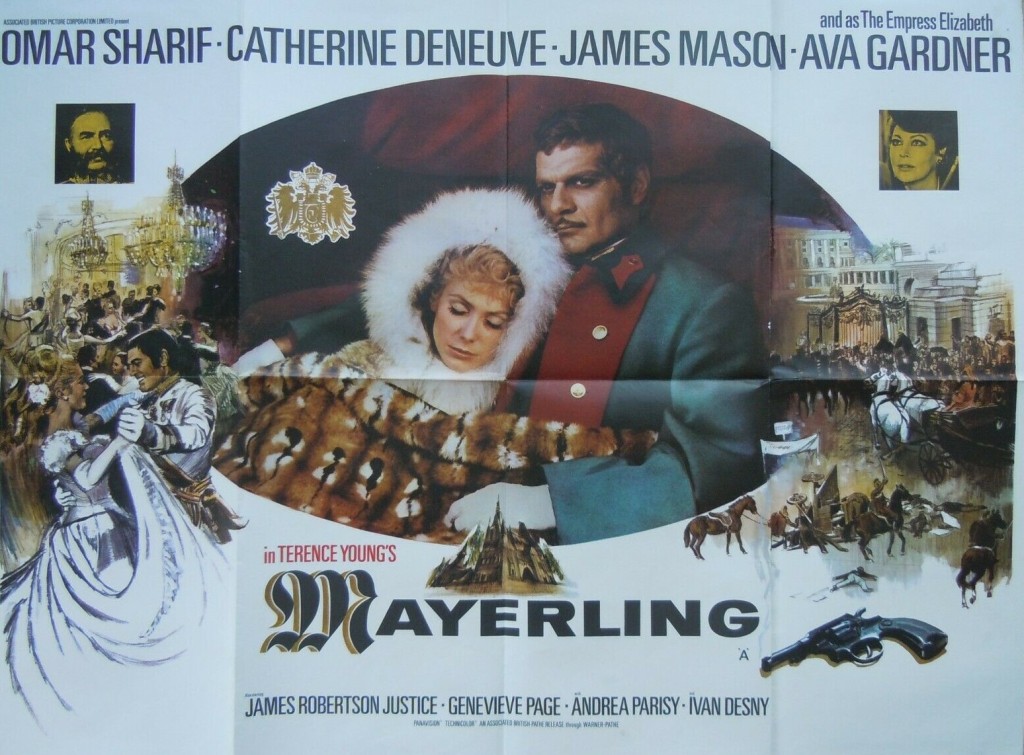

Catherine Deneuve (Mayerling, 1968) was a Hollywood irregular, not seen there in six years since March or Die (1977), and it’s surprising, never mind her choice of couture, what sophistication a French accent brings to a vampire movie. Susan Sarandon was an ideal fit for the European feel of the picture, having cut her teeth with Louis Malle on Pretty Baby (1978) and Atlantic City (1981). David Bowie spends most of the movie under a sheet of make-up so you need to get in quick for your Bowie fix, and for that short period he is quintessential Bowie.

Written by debutant James Costigan and Michael Thomas (Ladyhawke, 1985) from the Whitley Streiber bestseller.

But this is Tony Scott’s (Enemy of the State, 1998) triumph, work that you’ve never seen before and never seen since, making you wonder why he never continued in this vein.