Decent hokum sees Vikings ally with Moors to seek a mythical giant bell made of gold, “the mother of voices.” There are stunning set-pieces: a majestic long ship coming into port, superior battles, the Mare of Steel, the discovery of the bell itself, while a clever ruse triggers the climactic fight. There’s even a “Spartacus” moment – when the Vikings declare themselves willing to die should their leader be executed.

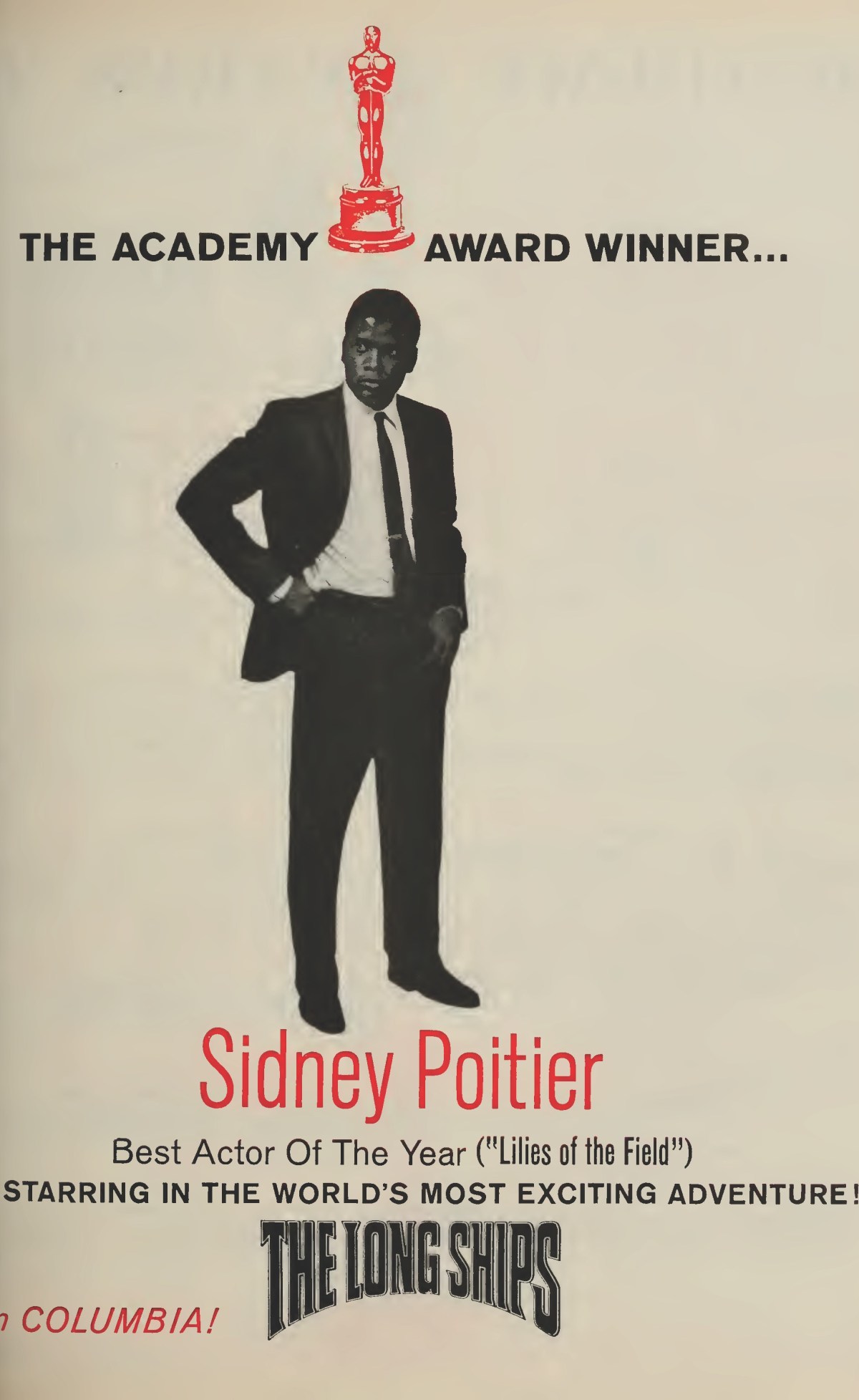

Rolfe (Richard Widmark) is the wily Viking, second cousin to a con man, demonstrating his physical prowess although he does appear to spend an inordinate amount of time swept up ashore after shipwreck. Moorish king Aly Mansuh (Sidney Poitier) is his rival for the legendary bell. The diminutive Orm (Russ Tamblyn), Rolfe’s sidekick, appears to be in a constant athletic duel with the Viking.

Although handy with a sword, both are equally adept at employing seduction, Aly Mansuh making eyes at Viking princess Beba Loncar (in her Hollywood debut) while Rolfe targets Poitier’s neglected wife Rosanna Schiafffino (Two Weeks in Another Town, 1962). The story is occasionally put on hold to permit the Viking horde to pursue their two favorite pastimes – sex and violence – and they make the most of the opportunity to frolic with a harem.

One of the marks of the better historical films is the intelligence of the battle scenes. Here, faced with Muslim cavalry, the Vikings steal a trick from The 300 Spartans by lying down to let the horses pass then rising up to slaughter their riders. But there is also an unusual piece of intelligent thinking. Realising, as the battle wears on, that they are substantially outnumbered and have their backs to the sea, Widmark takes the sensible option of surrendering.

Richard Widmark (The Secret Ways, 1961) makes the most of an expansive role. Instead of seething with discontent or intent on harm as seemed to be his lot in most pictures, he heads for swashbuckler central, with a side helping of Valentino, gaily leaping from high windows and engaging in swordfights. Sidney Poitier (Duel at Diablo, 1966), laden down with pomp and circumstance rather than immersed in poverty as would he his norm, is less comfortable as the Islamic ruler. (Widmark and Poitier re-teamed in The Bedford Incident, 1965, also reviewed in the blog.)

The puckish Tamblyn (The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm, 1962) almost steals the show. Both Loncar and Schiaffino have decent parts.

Director Jack Cardiff, Oscar-nominated for Sons and Lovers (1960), brings to bear his experience of working on The Vikings (1958) for which he was cinematographer. He is clearly at home with the action and equally there is some fine composition. However, the story in places is over-complicated, and he fails to rein in the mugging of one of the industry’s great muggers Oscar Homolka (Joy in the Morning, 1965) and there is a complete disregard for accent discipline. Edward Judd (The Day the Earth Caught Fire, 1961), Scotsman Gordon Jackson (The Great Escape, 1963) and Colin Blakely (The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes, 1970) have supporting roles.

Berkely Mather (Dr No, 1962), Beverly Cross (Jason and the Argonauts, 1963) and, in his sole movie credit, Frans G Bengtsson, collaborated on the screenplay.

Good fun and great to see Widmark and Poitier turning their screen personas upside down.