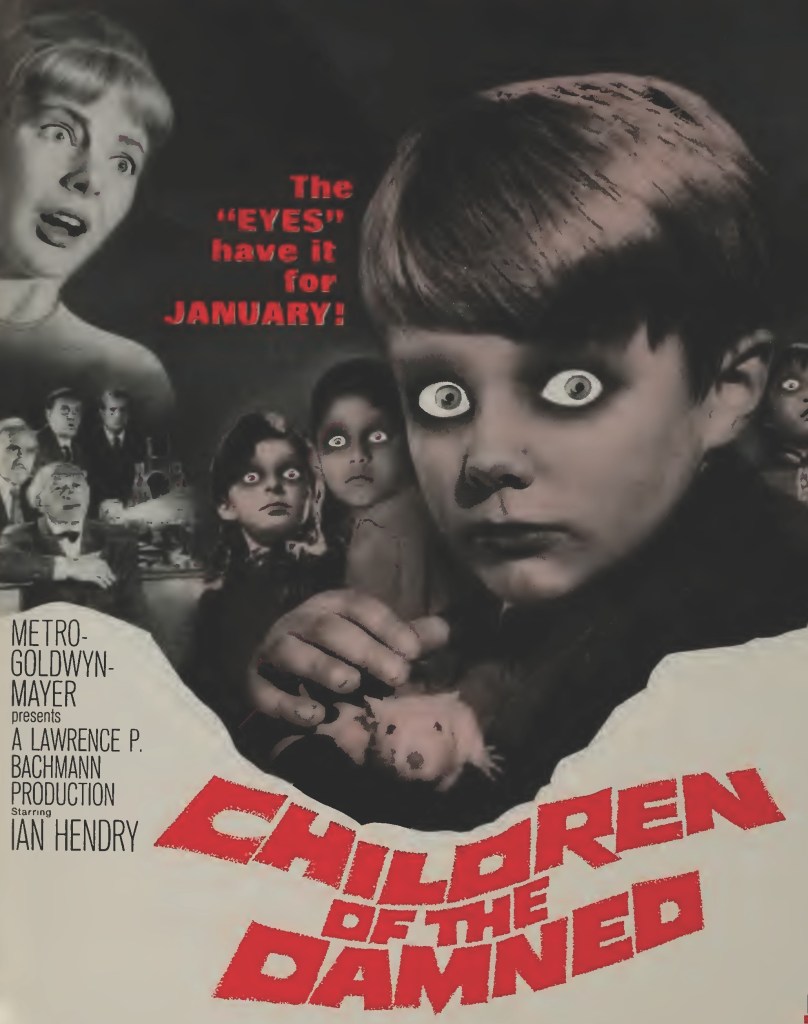

I wasn’t aware that celebrated sci fi author John Wyndham had written a sequel to his iconic novel The Midwich Cuckoos, filmed as Village of the Damned (1960). And it turned out he didn’t (he did make an attempt but abandoned it after a few chapters). So he had nothing to do with the sequel. But the original had proved such a hit MGM couldn’t resist going for second helpings.

And there was nothing the writer could do about it, it being standard procedure that when you sold your novel to Hollywood the studio retained all the rights and could commission a remake, sequel, turn it into a television series, without consulting you.

The only drawback for a potential sequel was that main adult character Professor Zellaby (George Sander) and all the kids had died in the original, though the final image of eyes flying out of the burning house might have suggested the children had actually survived. And, as we know these days, just when your main character dies it doesn’t prevent him miraculously returning to life should box office dictate.

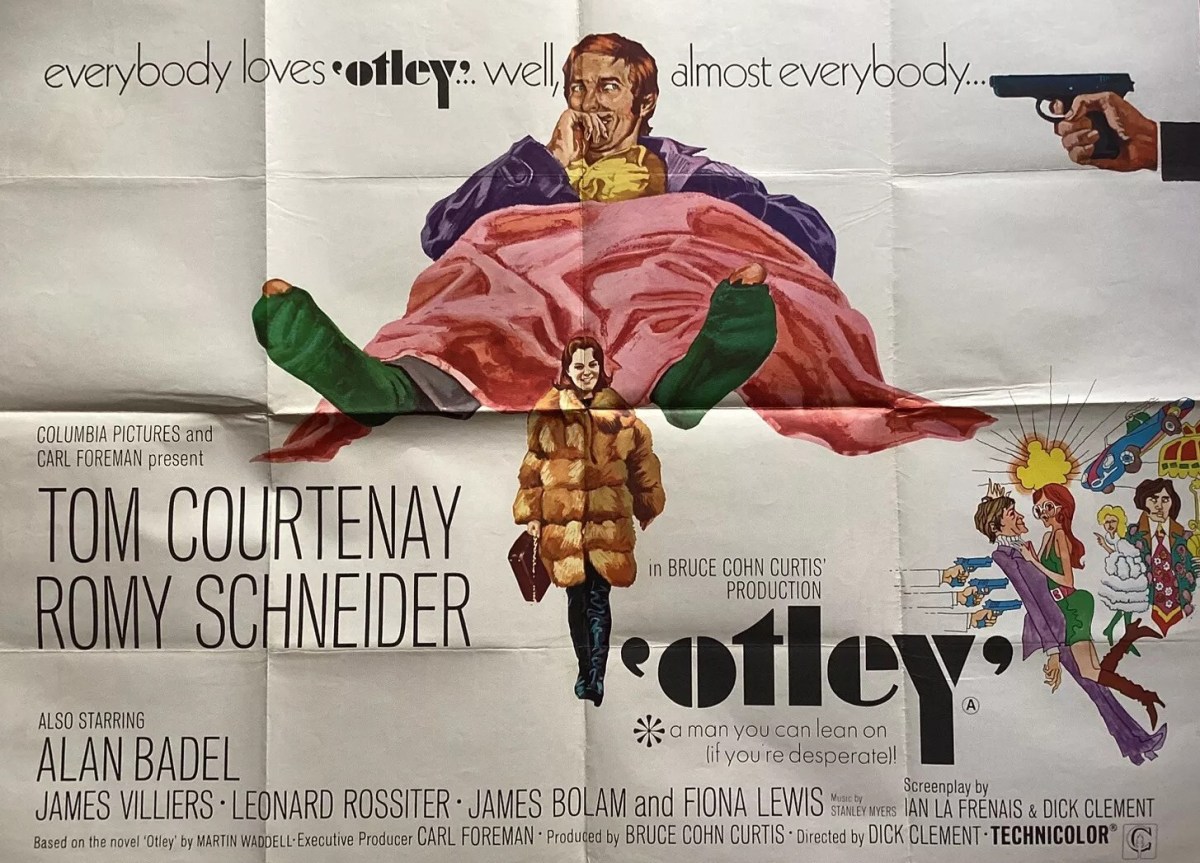

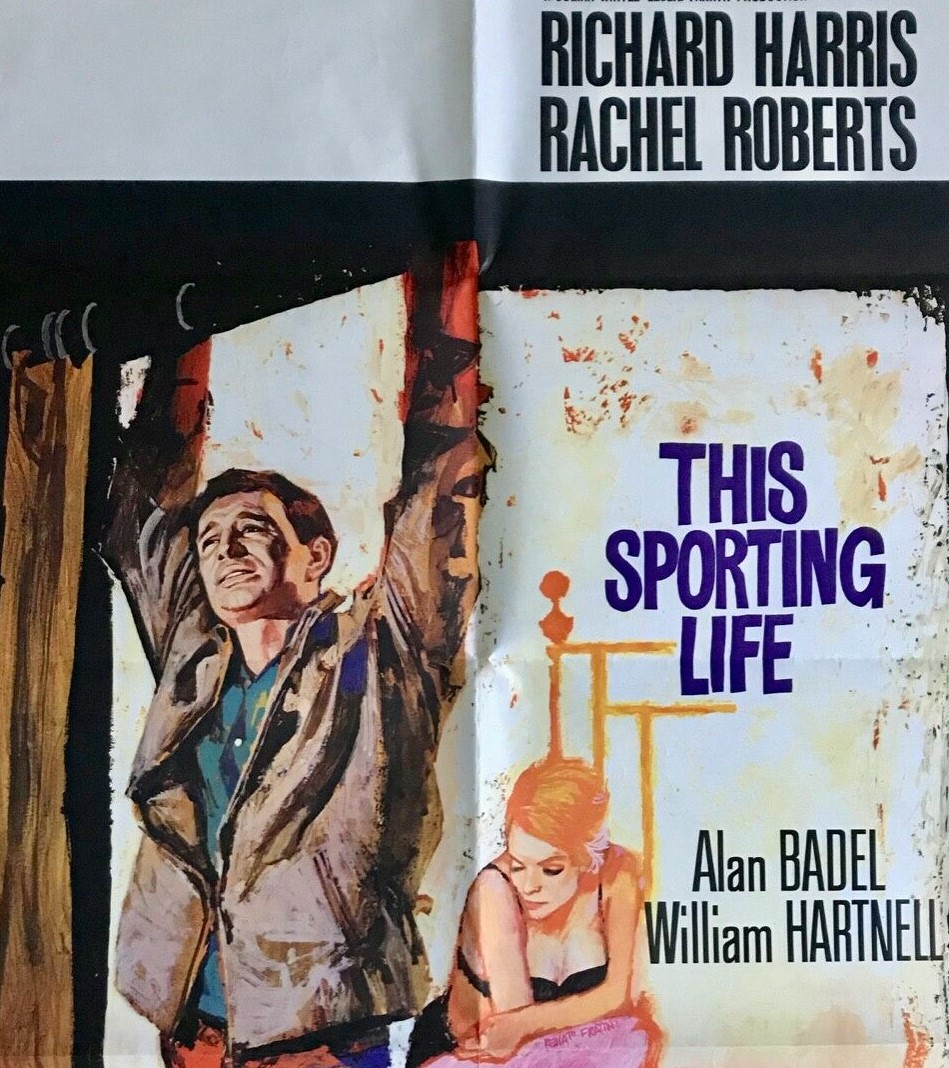

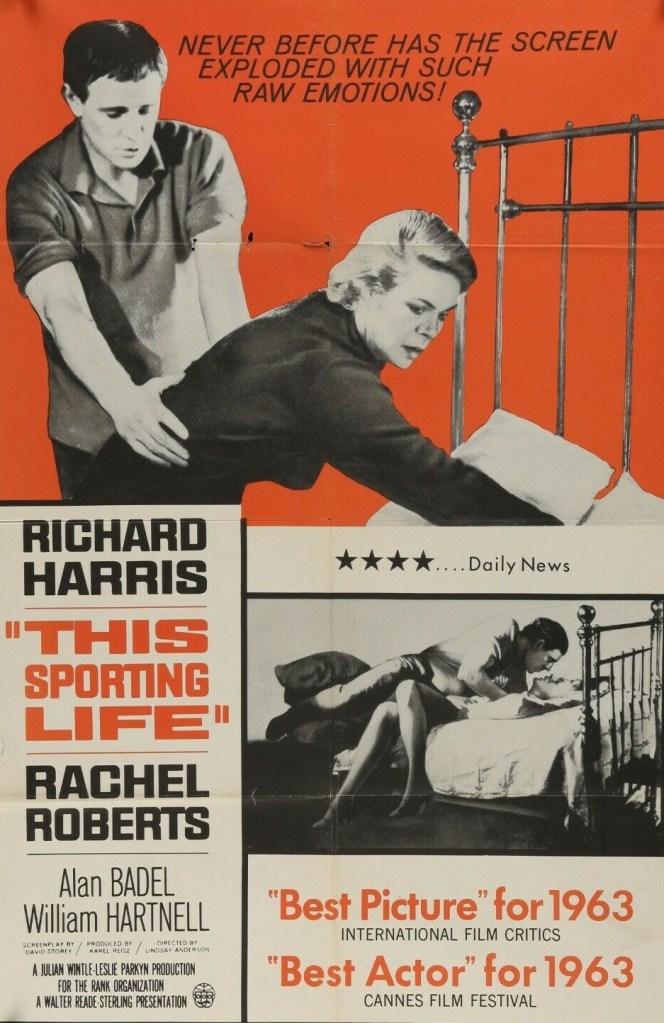

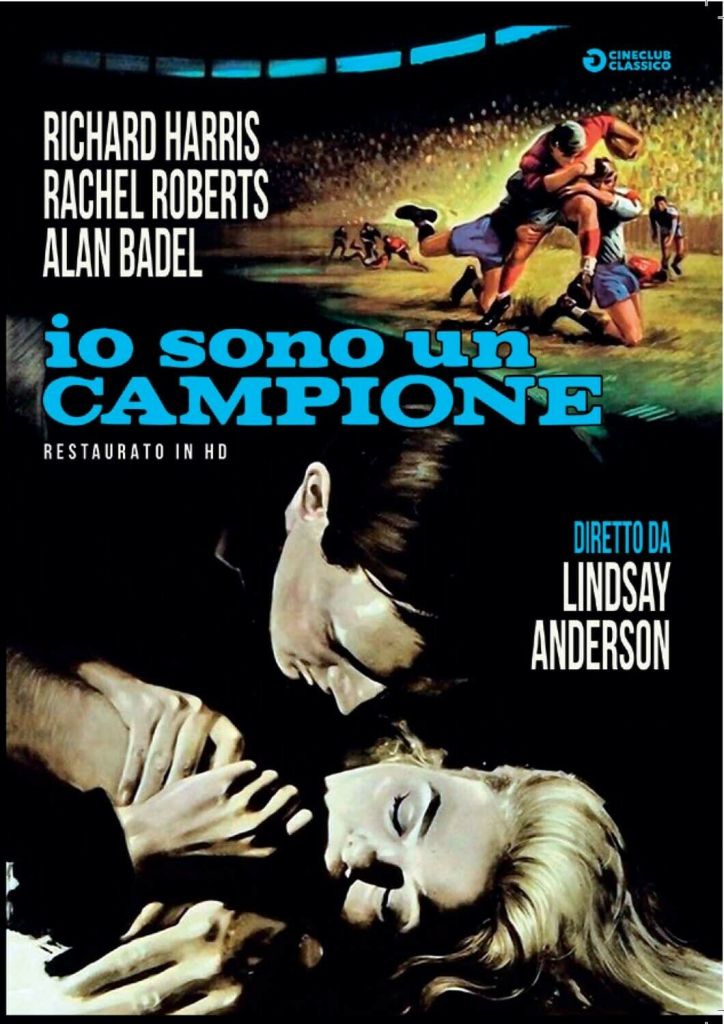

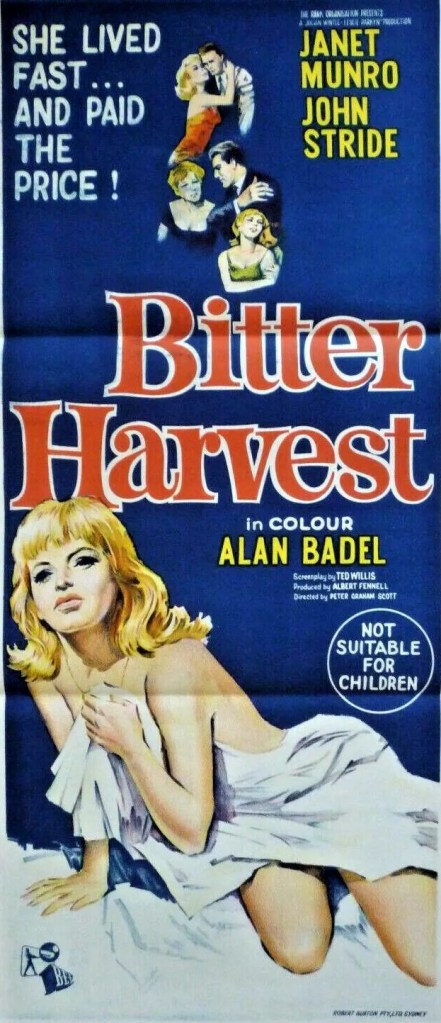

So screenwriter John Briley (Oscar-winner for Gandhi, 1982) was handed the sequel. And what we get is a lot of atmosphere, a chunk of running around in empty London streets (the result not of mass evacuation but filming in early morning when roads are clear), a very slinky turn from Alan Badel (Bitter Harvest, 1963) showing what he can do when hero not villain, and a twist on the previous problem – how to vanquish the kids – which is whether to weaponize them. Mostly, we are reminded of how better telekinesis was dealt with in the original picture and how poorly this compares to the likes of Brian De Palma’s later Carrie (1976) and even his The Fury (1978).

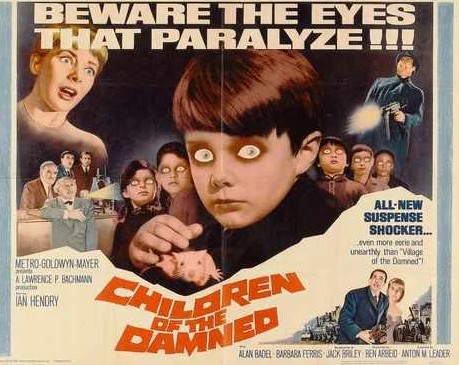

Apart from the title, there’s barely a nod to the previous incarnation, except that discerning the children’s paternity proves impossible. An United Nations project has tracked down six kids with incredible intellects. Like Professor Zellaby, British psychologist Dr Tom Llewellyn (Ian Hendry) and geneticist Dr David Neville (Alan Badel) want to study the kids while the more shadowy figure of Colin Webster (Alfred Burke) appears to have more sinister purpose in mind.

In any case none of the three achieve their goals because the kids escape and take refuge in an abandoned church, defending themselves against the authorities and the military by their brain controlling abilities and by the devising of a sonic weapon. Immediately under their thumb is the aunt, Susan (Barbara Ferris), of the young boy Paul (Clive Powell) who initially excited the interest of the British scientists.

Opinion varies as to whether the children are a genetic freak of nature, aliens or an advanced human race. The authorities can’t decide whether they are a threat or a wonder and decide to eliminate them, then change their mind, while the children decide to fight back then change their minds. The ending is quite a surprise.

Although the kids still have the fearful eyes, they are generally a lot less effective a scare than when the small gang of them stood side by side in the previous picture and stared at adults until they did the childrens’ bidding or killed themselves. There’s way too much discussion among adults. In the previous picture, those kinds of conversations had more emotional impact, since it was the villagers who were left distraught. Here, you couldn’t care less about the adults.

Interestingly enough, the standout isn’t any of the kids at all, but Alan Badel, who comes over as the libidinous sort, but very charming, and views any woman as fair game, but it’s fascinating to see how his usual screen persona here makes him a hero whereas in most other films exhibiting much the same characteristics he comes across as shifty, mean or downright villainous.

Ian Hendry (The Hill, 1965) was a rising British star but isn’t given much to get his teeth into. Barbara Ferris (Interlude, 1968) has a vital role.

Directed by television veteran Anton M. Leader (The Cockeyed Cowboys of Calico County, 1970) who makes his screen debut.

Not a patch on the original.