If you’re not Alfred Hitchcock with carte blanche to scare the pants off the audiences every which way but loose and you’re not launching a B-movie sexploitation drama, then you’ve got to take a more sensible path to selling a picture headlined by the world’s greatest hero Gregory Peck elevated to such a position by the extraordinary success of The Guns of Navarone (1961) which topped the annual box rankings in the USA.

So while your taglines can emphasize “shock and suspense” what you’re selling cinema managers is quality. So, in the Pressbook/Marketing Manual, Peck is portrayed as a “celluloid perfectionist” and “four-time Oscar nominee” so multi-talented he’s a triple hyphenate – writer, producer, actor. Such a perfectionist he’s known “to spend a week or more preparing for one small scene.”

He is a class act not some sleazy B-movie bum. “He not only completely absorbed all the dialog, its various nuances and shadings, but also probed the psychological and physiological motivations of the attorney he portrays,” notes the Pressbook.

And it’s not just Peck who’s to be praised. “Seldom has such an outstanding array of talent been so tellingly marshaled for such a dramatic thunderbolt.”

The messianic tone is evident throughout. Headlines claim “Bob Mitchum’s career reaches a new high,” Lori Martin has the “top role” of her career, Barrie Chase is “praised as top talent discovery” and “Telly Savalas termed top talent find by Peck.”

Polly Bergen “emerges as an actress of great sensitivity and insight.” Lori Singer, in her movie debut, “graphically attests to the polish she has achieved through her work as child lead in the video (television) series National Velvet.” Although Martin had another reason for turning up word perfect – so that she could get off early and go ice skating.

And the praise doesn’t stop there. “A whole new career should open for sultry Barrie Chase, one-time dancing partner of Fred Astaire.” She is “sensationally good as the casual pick-up ensnared by Mitchum.” The talent pickers had no doubt she was “destined to become one of the foremost dramatic talents of the industry. The very quality which made her such an outstanding dancer – her tireless attention to even the minutest detail – has helped turn her into a magnificent actress.” The marketeers were convinced her “masterpiece” performance would result in an Oscar nomination.

Peck had appointed himself the “tub-thumper” for Savalas after seeing him play Al Capone” in the television series The Witness (1960-1961) calling him “one of the finest new talents of the last 10 years.”

According to the Pressbook, director J. Lee Thompson “deliberately imparted…a distinctively British touch.” Claimed Thompson, “There emerges in the best of the British pictures a certain warmth and credibility which are looked upon as the English hallmark. Such an impression is achieved, it seems to me, through the simple technique of emphasizing character development.”

For journalistic snippets there’s not much beyond that Peck was so impressed with the location in Georgia that he purchased a plot of land on Sea Island to build a beach house. Plus that he’s turned into a noted photographer, now onto his seventh camera with a fast lens. Polly Bergen was creating a nightclub act. Robert Mitchum was thrown three times on his first film horse.

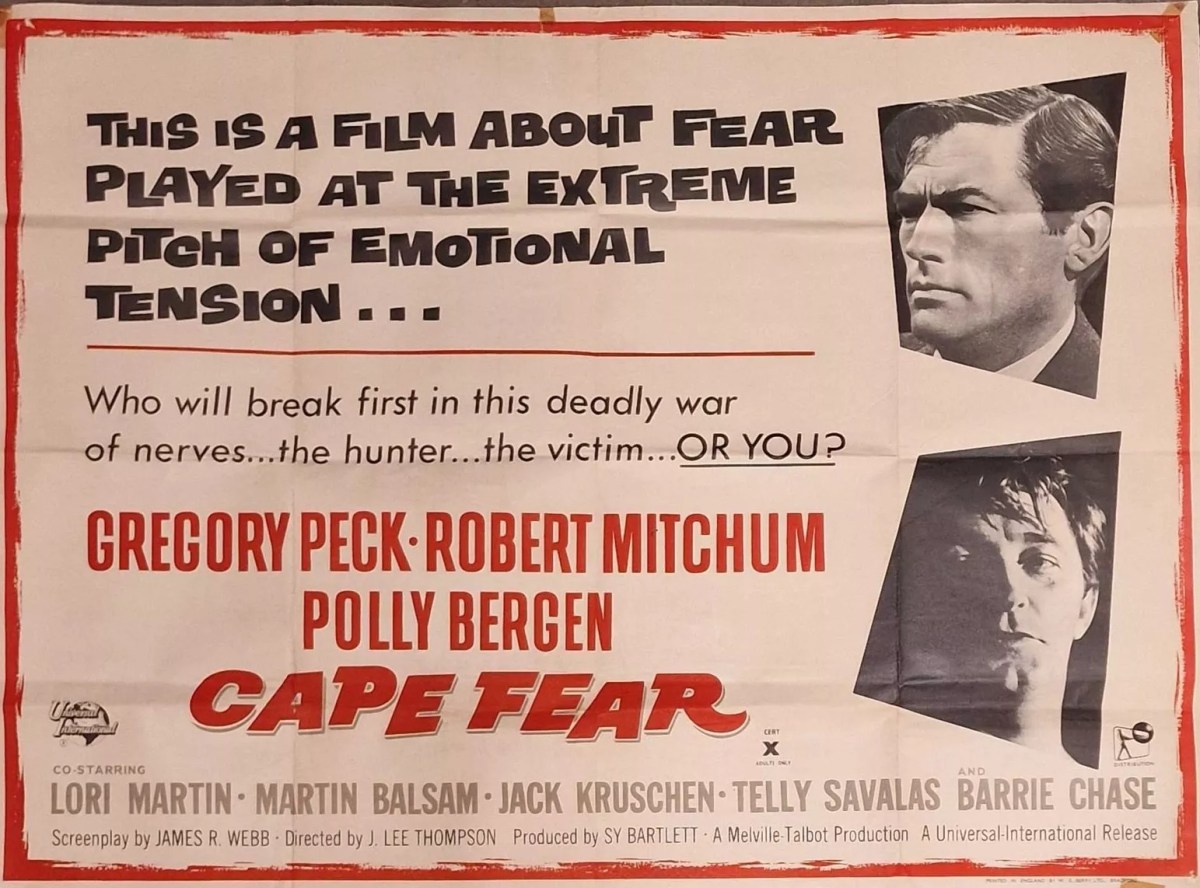

But it was unlikely that cinema managers would find a way of passing on to audiences the idea that this was a “quality sleaze” picture populated by proven and up-and-coming talent. The public had to make do with posters and taglines to get a feel for what was on offer. And in that respect the marketeers pulled few punches.

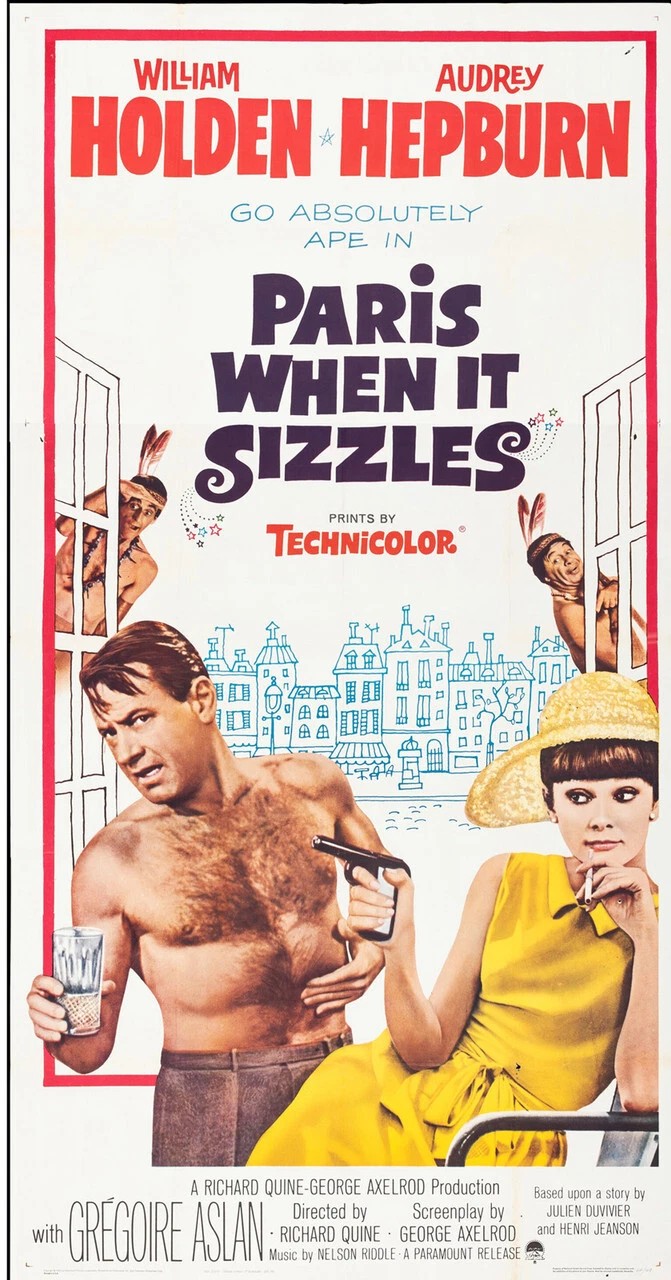

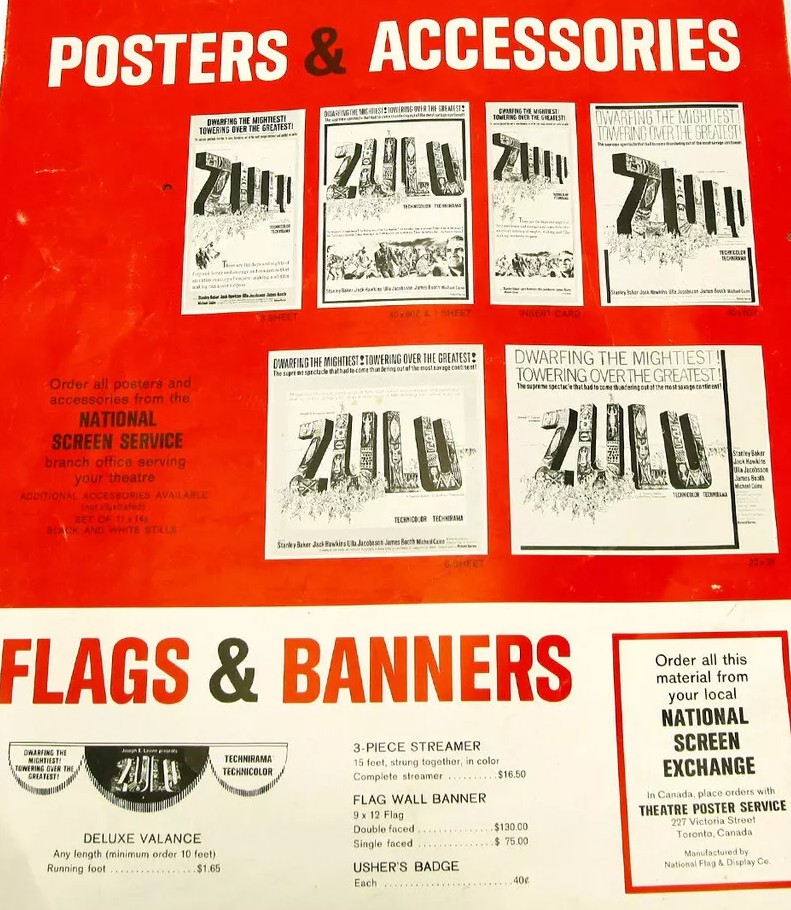

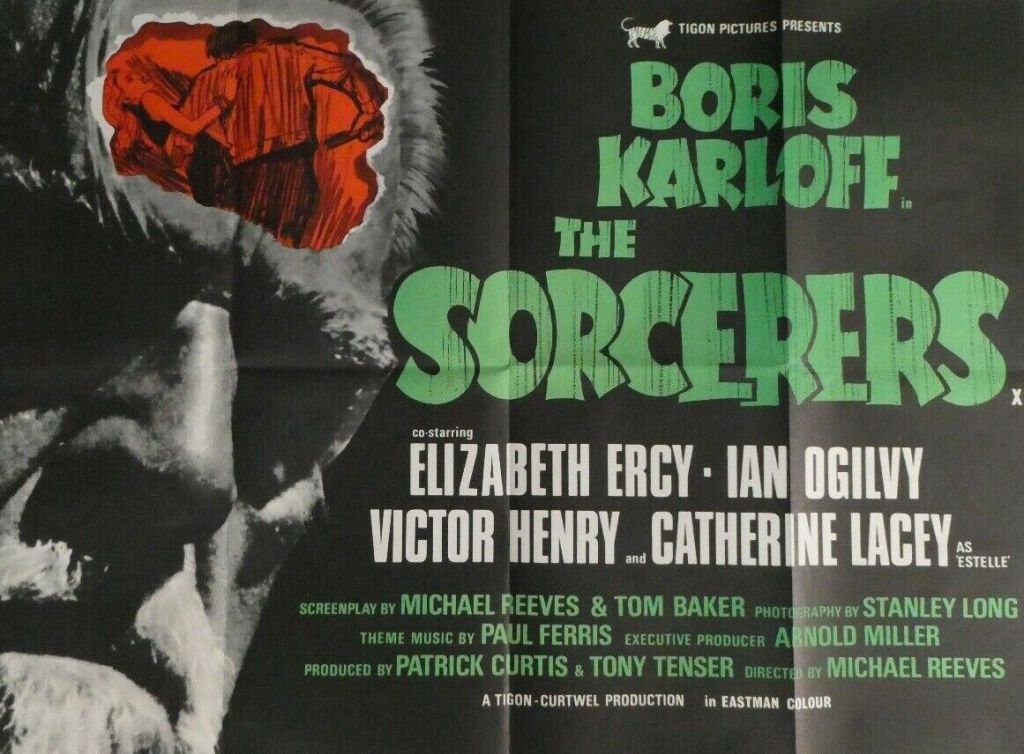

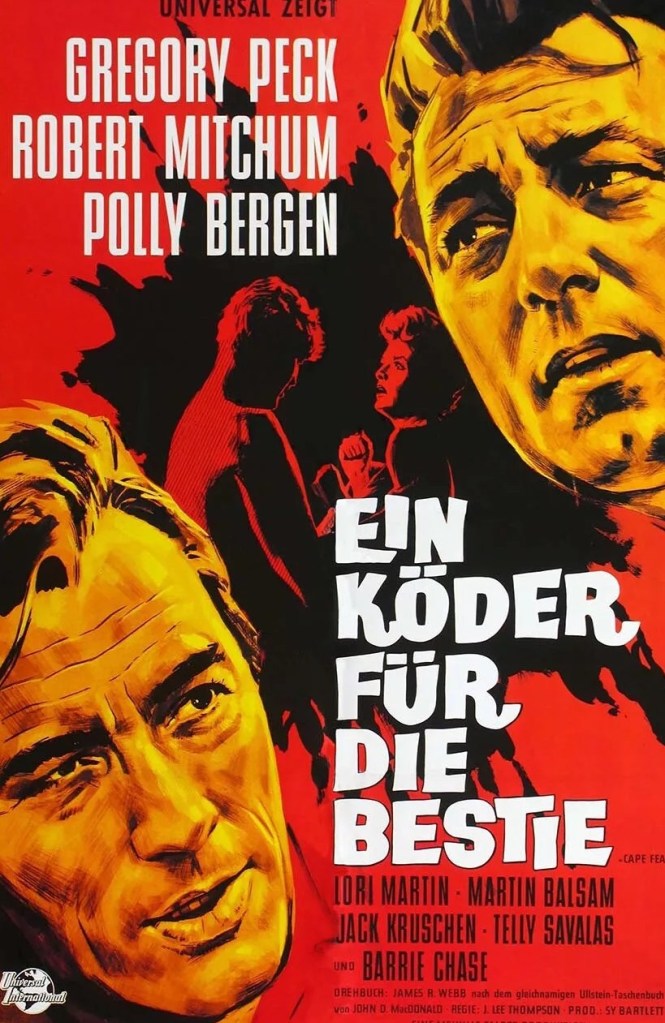

As usual, cinema managers were offered a plethora of choice when it came to the posters. Mostly, Peck and Mitchum were shown on opposite sides of the poster with in between an image intended to conjure up menace – the bare-chested Mitchum confronting Bergen, Bergen comforting her daughter, mother and daughter running, Mitchum tangling with the daughter.

Taglines spelled it out in a variety of ways: “A terrifying war of nerves unparalleled in suspense!” with a sub-tag of “A man savagely dedicated to committing a crime shocking beyond belief! A man desperately determined to end his ordeal of terror…even if it meant using the ultimate weapon – murder!”

Exclamation marks were in full flow. “Now, he had only one weapon left – murder…to prevent an even more shocking crime” was backed up by “the drama of an unrelenting war of nerves…and the helpless lives that were caught in its terrifying crossfire!”

Or try this – “The savagely suspenseful story of an unspeakable crime…and the man, the woman, the helpless people it touched with terror. From the moment they meet the tension is explosive. An electrifying war of nerves unrelenting in suspense!”

In case you didn’t get the message, here it is in more subtle form: “What happens to them in an adventure in the unusual!” That understatement is followed up with “So daring in theme…so frank in treatment…that it frightens while it fascinates and gives a terrifying new meaning in suspense!”

And there were variations of the above: “A terrifying war of nerves unparalleled in suspense! The Watched…who can only run so far before coming face-to-face with The Watcher…who waits for the moment when the woman and her daughter will be alone.”

And – “Now the nightmare was about to become a terrifying reality… the whispered threat a crime unspeakable. So daring in theme…so frank in treatment. What happens to them is an adventure in the unusual!”

Plus – “Their ordeal of terror triggers the screen’s most savage war of nerves! Unparalleled suspense…as one becomes a target for nightmare, the other becomes his target for execution.”

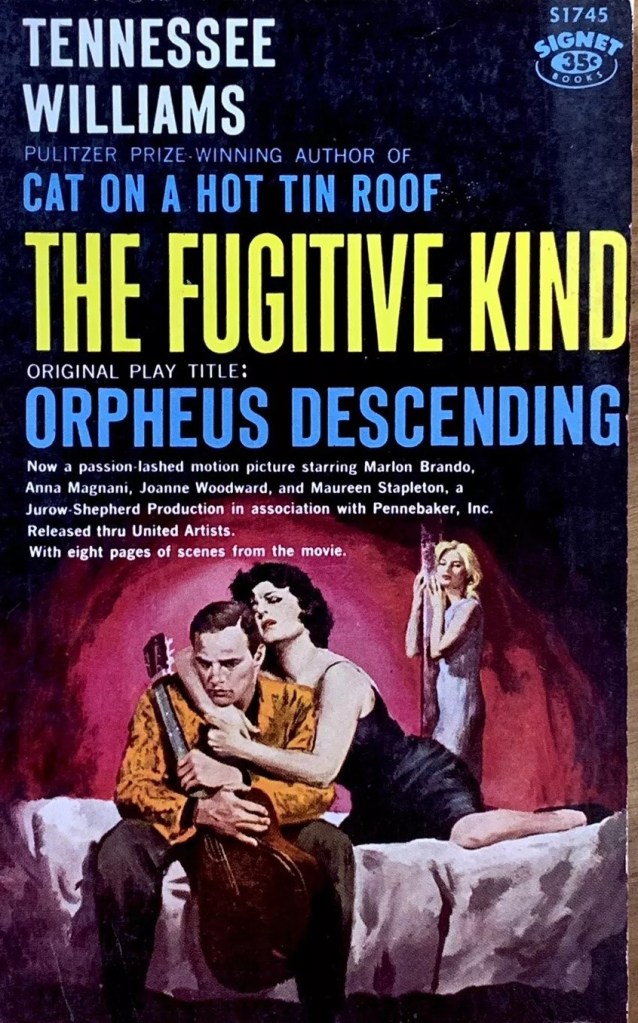

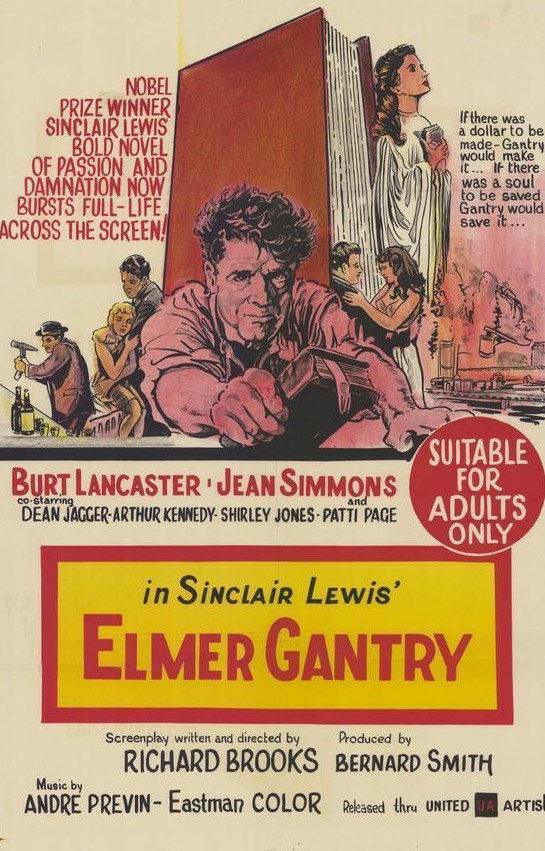

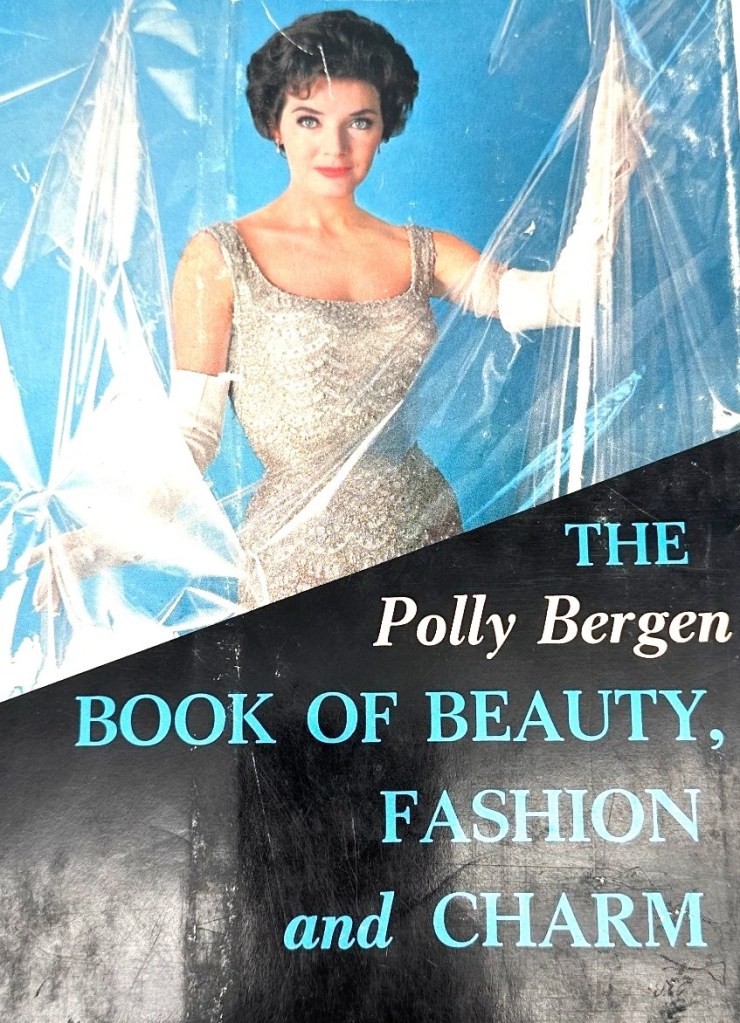

Unusually, there were a host of promotional items. As well as a motion picture paperback edition from Fawcett, “hot off the press” was the Prentice-Hall hardback The Polly Bergen Book of Beauty, Fashion and Charm, including stills from Cape Fear. Books were a major source for marketing, given there were over 100,000 outlets in specialist shops, drug stores, railway and bus terminals and carousels on newspaper stands.

Virtually any homely element of the movie was co-opted for promotional purposes. A scene taking place at a United Air Lines terminal counter provided opportunity for tie-ins with travel agents and ticket offices. Bowling “palaces” might be happy to display posters and promotional material given there’s a scene set in a bowling alley. Distributors of a Chris Craft boats, Chrysler station wagons, Larson speed boats and Scott outboard motors – which all appear in the movie – could be targeted.