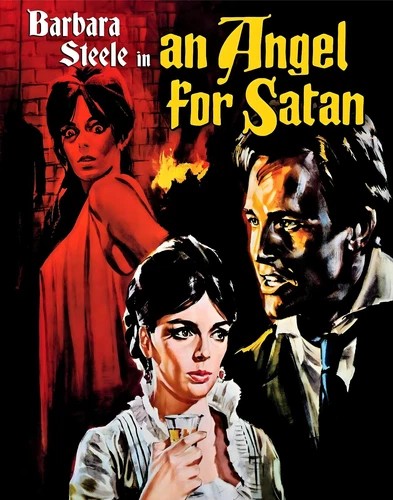

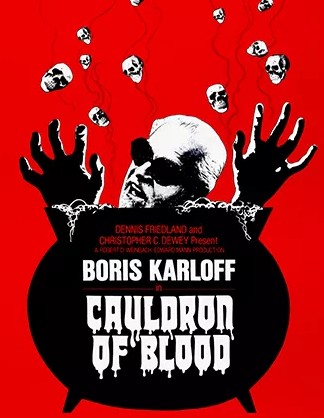

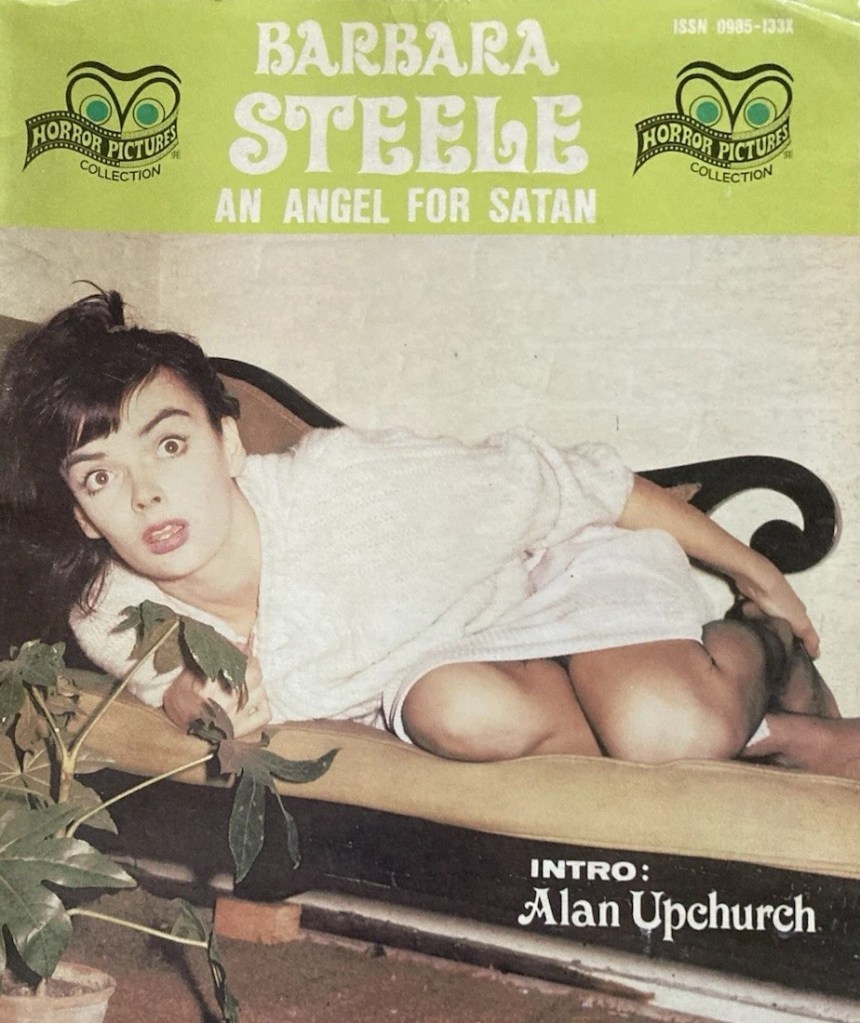

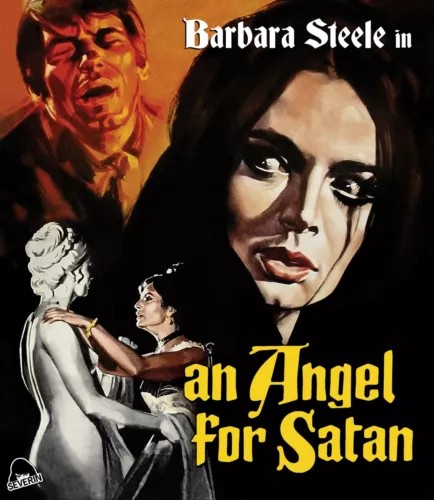

Scream Queen Barbara Steele (The Crimson Cult / Cult of the Crimson Altar, 1968) is the big attraction in this heady brew of witchcraft, ancient curse, hypnotism and plain ordinary seduction, with an ingenious double twist. And elegantly mounted, crisply photographed as if a Hollywood picture of the 1940s.

After a drought lowers the water level, a 200-year-old statue of the beautiful Countess Melena is recovered from the seabed. The locals fear it carries a curse. Artist Roberto (Anthony Steffen), hired to restore the artwork, arrives only days before the young countess Harriet (Barbara Steele) returns to claim her inheritance. With some clever sleight-of-hand, veteran Italian director Camillo Mastrocinque (Crypt of the Vampire, 1964) misleads the audience into thinking this is all about secret love affairs, Harriet’s uncle the Count (Claudio Gora) in an illicit relationship with housekeeper Ilda (Marina Berti), maid Rita (Ursula Davis) tempting timid schoolteacher Dario (Vassilli Karis), nascent love between Harriet and Roberto hitting a stumbling block and various shades of unshackled lust from woodcutter Vittorio (Aldo Berti) and village strong man Carlo (Mario Brega).

But pretty quickly, the picture takes a different turn. Turns out it’s not Melena who’s the problem – but her jealous ugly cousin Belinda who threw the statue into the water in the first place. Whatever the cause, there’s an outbreak of malevolence, mostly emanating from Harriet.

She strips naked for Carlo then savagely beats him for daring to stare at the nude body. She seduces Dario, looks like she’s making a play for Rita, goads Roberto and tells him she likes violence and has Carlo in her thrall.

In short order a female villager is raped and murdered, another barely escaping a similar fate, the schoolteacher commits suicide, several villagers are axed to death, the strong man sets fire to his cottage, killing wife and seven children, and the woodcutter is speared by pitchforks.

You can tell this is a classier number because the violence is minus any gore and there’s little attempt at deliberate shock, more of a slow burn as Harriet torments those around her. Roberto is permitted small touches of investigation, and there’s a clever special effect of a painting appearing to talk.

The traditional horror elements – lightning, slamming windows, storms – are primarily employed to nudge Harriet and Roberto together; it just so happens that she is scared of lightning and he’s the person most conveniently placed to comfort her. There’s a hint of the narcissism found in Hammer’s later lesbian horror pictures, and only the censor or the director’s discretion prevents more full-blown nudity as a prelude to seduction of both male and female. Harriet’s a dab hand at inveigling males to be in the wrong place at the wrong time invariably with her clothes in disarray to lend substance to her claims of being attacked.

While, as regular readers will know, I’m generally in favour of the climactic twist – the more the merrier – here I’m not so sure this was the road to go down. As Roberto already knows that the curse applies to wicked cousin Belinda rather than Melena, it would have been enough for him to declare this and find a way of removing it, most likely adopting the simple solution of chucking the statue back in the sea, which is what the villagers have been demanding all along.

It’s quite clear that much of the rape and killing is down to hypnotism by Harriet, but once we discover she’s being hypnotized by the Count, in one fell swoop what had been an intriguing horror story transforms into a more run-of-the-mill crime tale since if Harriett is committed to an asylum then he can continue to rule the roost.

But he’s in the thrall of Ilda who turns out to be the ancestor of Belinda. So not quite the satisfactory ending unless the criminal element had been introduced earlier on.

I doubt if Barbara Steele fans will care as the actress is very much in her element and, although in the end a victim, for the bulk of the picture she is in total – and seductive – command. Nobody’s going to compete with her and sensibly nobody tries. Anthony Steffen didn’t need any help with his career because had had already headed down the spaghetti western route.

Classically directed – excellent composition and camera movement – from a script by Mastrocinque and Giuseppe Mangione (Anzio / Battle for Anzio, 1968) from a novel by Antonio Fogazarro.

Superior stuff in which Barbara Steele shines.