Terrific twist-a-minute thriller. Forget its arthouse origins. The gap of half a century since its initial appearance has worked in its favor and you can now view it as exceptionally gripping entertainment. The Swedish setting doesn’t mean it’s drenched in angst and repression, and instead pivots on that other Swedish contribution to cinema of that decade of sex and nudity. Though power games these days tend to belong to the horror vernacular where innocents stray into the wrong location – Barbarian (2022), Heretic (2024) – outwith such business-set items as Working Girl (1988) and The Devil Wears Prada (2006), this belongs to an earlier version of the cycle which relies on sexual undertones.

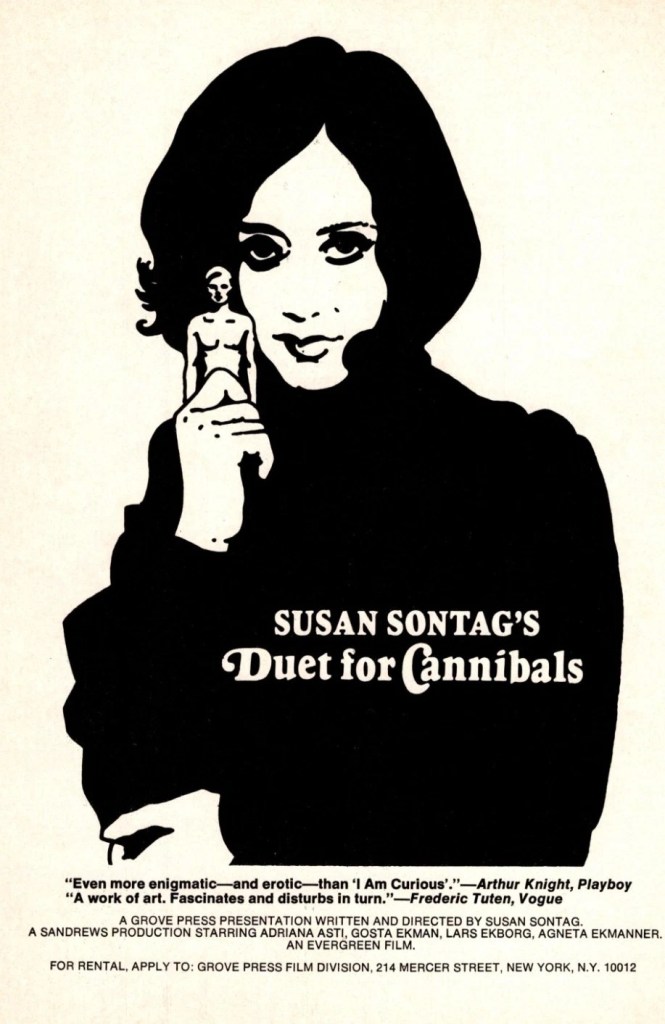

This will most likely be touted as worth a look because it was one of the very few – less than a dozen – movies directed by women in the 1960s. While Swedish actress Mai Zetterling was the jointly the most prolific with four films beginning with Loving Couples (1964) and Frenchwoman Agnes Varda, also with four, the most acclaimed following Cleo from 5 to 7 (1962), American Susan Sontag’s debut – she also wrote the piece – was the most highly awaited. Through her writings she was something of an outspoken icon and an intellectual powerhouse.

Instead of holding four figures in her hand the woman now holds on.

Made in Sweden with a Swedish cast and while originally seen as Bergmanesque or perhaps Pinteresque, a contemporary audience is more likely to ignore the other influences and settle for the innocents walking willingly into a trap. Tomas (Gosta Ekman) goes to work for enigmatic political exile Dr Bauer (Lars Ekborg). His duties mostly involve curating the revolutionary’s life’s work, transcribing diaries and such, but occasionally he is called upon to do what appear to be simple acts of espionage, nothing dangerous just delivering a mysterious parcel.

Dr Bauer is pumped up with his own importance and expects employees at his beck and call – Tomas has to sleep there, in a made-up bed in the library – and enjoys the power surge of bawling people out when minor mishaps occur. But he also enjoys – if that’s the word – a peculiar marriage to younger Italian wife Francesca (Adrianna Asti) who while doe-eyed is far from docile. On her first encounter with Tomas, Francesca breaks a window and it’s not long until she exerts a sexual lure.

Tomas dreams of making love to her and would watch her making love to her husband in a car in the garage except Francesca obscures the windscreen with shaving foam. That scene in itself is one of the most intriguing. She has thrown an almighty sulk, locked herself in the car, ignoring her husband until she starts the engine and nearly mows him down at which point the tempo dramatically changes triggering for a bout of heavy sex.

This appeared in 1970.

Theoretically, Dr Bauer is dying from a mysterious illness. You get the sense he’s auditioning Tomas as someone to look after his wife when he’s gone, but all of that could just be part of the game.

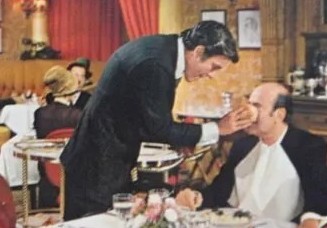

There’s a marvelous scene where Tomas is encouraged to continue eating at the dinner table to the soundtrack of Dr Bauer throwing up in the toilet. When the doctor returns, he heaps food on his plate and continues eating.

Dr Bauer isn’t just paranoid – the cook’s poisoning him, his phone’s tapped, Tomas is a spy, his wife’s planning to kill him – but he’s also a narcissist, studying his face in the mirror, improving his appearance with wigs and a painted-on aesthetic beard. He encourages potential intimacy by having Tomas read poetry to his wife.

She’s the dominant one in her fantasy, rescuing Tomas from an enchanted castle, standing above him on a stool, bandaging his face so that as a mummy he can terrorize her in sexual fashion. She puts her husband’s perennial sunglasses on his eyes. Sometimes her husband’s head is bandaged.

Braun plans to kill his wife because “there’s no point keeping her alive.” Equally, she, apparently is intent on returning the compliment though she wants Tomas to do the dirty deed. Or it could be a murder-suicide pact.

She locks her husband in her bedroom closet so she can make love to Tomas while he listens but he also has key to the door and could let himself out at any time. When Tomas’s girlfriend Ingrid (Agneta Ekmanner) enters the equation Tomas is forced to watch her making love to Dr Bauer. And it’s not long before Tomas is chucked out and Ingrid sucked in. In one of the most erotic scenes you’ll ever witness husband and wife feverishly feed Ingrid with their hands and before you know it she’s sharing their bed.

Even within the confines and the mathematical possibilities of the power play, you still never know which way this is going to turn. You might quibble at the voice-over which attempts to play much of the goings-on through Tomas’s POV and the flirtations with left wing politics, but those are easy to ignore as you are carried along on the twists and turns. It keeps twisting till the very end when the stings in the tail come fast.

These days it would be played at a higher tempo, the melodramatic elements ramped up, but actually the lack of emotional heft works to its advantage. Terrific debut from Susan Sontag. The slinky Adriana Asti (Love Circle, 1969) steals the show.

Rare find.

Catch it on Netflix (great print) or YouTube.

Should you be interested YouTube has an interview with both Sontag and Varda.