Unusual and unusually effective entry into the low-budget British B-film crime category. Teeters for a time on the bittersweet before plunking for ending on a more realistic sour note. Surprising, too, in being issue-driven – the problem of the rehabilitation of criminals, or the way such efforts are blocked by the general populace wanting nothing to do with thieves and villains, especially when it comes to employment or romance.

On release from prison, George (David Sumner) is given the chance of a new life from do-gooder Tom Daniels (James Hayter) who runs a halfway house for ex-cons. George isn’t particularly grateful, since he sees life stacked up against him. But he’s making an effort and turns down the chance to join the other residents in setting up an illegal scheme. Instead, Tom finds him work as a driver for a furnishings manufacturer where he meets Muriel (Mela White). But their nascent romance is scuppered when the cops come calling, investigating a murder on the “Flats”, an area of wildland close to both the factory where he works and the pub he frequents.

When the killer strikes again, and again, the cops Det Supt Chadwick (John Arnatt) and Sgt Tracey (Jack Watson) realize the murderer is striking at the full moon. Luckily, neither of the detectives is apt to go down the werewolf route, especially as the killer tends to strike when a full moon would be of little assistance because the “Flats” are covered in thick fog (for no apparent reason except the script says so).

George becomes the chief suspect and the cops decide to set up Sgt June Lock (Susan Travers) as bait – odd how often this became a trope in these B-pictures. She’s to befriend George and, come the full moon, prevent herself being killed (the cops are keeping tabs on her) long enough to trap George as the killer.

There’s generally little time to waste in these running-time-conscious thrillers (this only lasts 68 minutes) on any characterization beyond the obvious but here we discover George has been disowned by his mother, a rather well-off character who lives in a good-sized house in middle-class Chiswick. When he asks to be allowed home, she turns him away and when the cops come calling her first words are, “I don’t have a son.” She’s a cold fish for sure, and hardly the entire reason he’s turned to crime, but it would go some way to explain his general bitterness.

George also appears to have an artistic bent and June encourages him, going so far as lining him up for some work. Before we get to the finale, there are other treats in store, the shrewish mother Mrs Foster (Hilda Fenemore) of the sulking Lily (Coral Morphew) who escaped attack by the killer. The other occupants of the house are also well-drawn, with a villainous hierarchy in operation, and clearly much more likely than George to re-offend.

The cops, too, are more ready than usual to admit defeat. Clues are non-existent what with the fog and any attempt at forensics limited to wondering why George cleaned his shoes so assiduously, the obvious deduction being the existence of mud or grass would have put him close to the crime scene.

In truth, there’s not much to the detection, but at least, as I said, nobody falls for the werewolf line and the idea of the date bait seems to come too easily to the cops.

As it stands, it’s mostly a character study, of a young man who can’t get a break, of society’s attitude to criminals, the lack of redemption available and little chance of a second chance once your past is discovered. I’m not sure how much this was an issue at the time but George exhibits a more understandable seam of bitterness than the likes of the surly Arthur Seaton in Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (1960). The movie only scratches the surface of the affect of a child on the lack of a mother’s love, and since we don’t know what triggered George’s first crime it’s hard to go any deeper.

There’s the chance of a happy ending. June is clearly smitten with George and determined to prove him innocent rather than, as her superiors require, guilty. But bitterness wins out in the end.

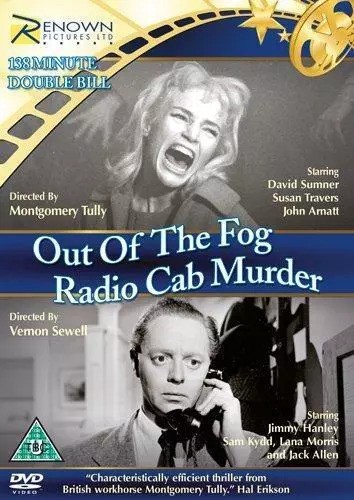

Directed by Montgomery Tully (The Terrornauts, 1967) who had a hand in the screenplay along with producer Maurice J. Wilson (Master Spy, 1963) based on the novel by Bruce Graeme.

David Sumner (The Long Duel, 1967) gets his teeth into a peach of a part. Career-wise Jack Watson (The Hill, 1965) fared best though Susan Travers (Peeping Tom, 1960) had a running role in TV series Van der Valk (1972-1973)

Interesting twist on the genre.